Laling’s eyes have special powers. Her black irises glisten in clear white pools. She can see when we tell a lie. Her eyes fix on us and we confess. We perk up when she’s happy and wilt when she’s mad. Only Johanna is impervious to her “hwag!" (don't do it!) or "halaka!" (I'm warning you, watch out!). And Laling's eyes cannot stop a skirmish between Scotty and Jo. But Laling is Johanna’s yaya, so Johanna is forgiven 70x7.

Laling takes a break from plantsa. The concrete step near her offers evidence of chicken tonight: dry blood with feathers. Laling doesn’t notice me. She leans on the threshold with her hands behind her. She’s not smiling, not frowning, just looking faraway. I think: she is tired of us and my heart hurts.

My blond big brother Scotty comes around the corner, “Whadaya doing?”

“Diging ta China.”

“Bobo, you kannat dig a hole ta China.”

“YES I can.”

“Bobo. No you can’t.” He kicks my pile of dirt a little.

I hit him with the spoon, “STOPET! Bobo ka!! Laling!” She looks at us wearily but doesn’t move.

Scotty sees Laling and changes tone. “You kannat dig a hole ta China. BeCAUSE. China’s beside da Pilpines.”

“So hwat!” I don’t get it.

“So you kannat dig der,” with the authority of a second grader.

“Oh,” in a small voice, “Hway?”

“BeCAUSE China’s beside da Pilpines!”

I look at him warily. I still don’t get it.

“How ‘bout da States. You kan dig to da States!” Excited, because he’s found a way for me not to be bobo, he tries to grab my spoon to help me. I whisk it away just in time.

“Ok!” I say happily. I'll dig to granmother’s house.

In my hole to granmother’s house, I find an old brass piece.

“What’s dis, daddy?” I hold it out to dad in his downstairs study.

“Hmmm,” he turns it over. “It’s a shell casing from a bullet, maybe World War II.”

It goes into a special box that I keep under my bed.

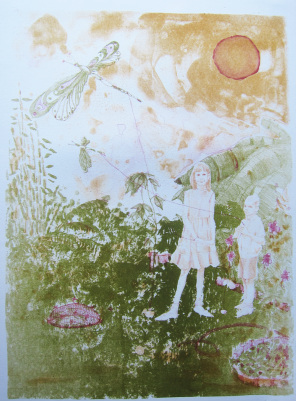

Tutubi, by Johanna Poethig

Tutubi, by Johanna Poethig Phyllis Monteclaro is my best friend. We call her “Feelees.” She’s soft, round, and calm. I’m boney and too excited. Our unlikely union will follow us all the way through 7th grade. She’s a careful perfectionist; I'm quick and clumsy. Note the difference between our macrame bags in Mrs. Sayo's 6th grade Home Ec class. Her string bag could be merchandise at Rustan's Department Store; my knots are moody. "Well," says mom diplomatically, "yours is original."

Felees, two brothers and sister and parents and a relative or two live in the big rambling house beside us. Their father is an editor for Manila Bulletin newspaper He's round and friendly like Phyllis, but when he's there, I'm shy. Feelee's mom is spry like her older sister. Her mom is warm and chattery and always gives us better merienda than at our house. They are Baptist and so they don’t attend Ellinwood church.

“Feelees, Feeleeeees, FEELESS, ” I call through our screen to her porch, “can I come ober?” Someone at her house tells Feelees that the kana next door is making a fuss again, so she waves to me from the porch, and I run over: down our steps past House #A, unlatch the big green gate of our compound, relatch, and run to her gate. Someone comes down to let me in. We play patintero on their driveway with her sister, brothers and anyone else. Or they watch Popeye on the b&w TV in the Airconditioned Room. We play hideandseek everywhere.

We begin our friendship at Harris Memorial School Kindergarten. A minibus picks us up. Mom ties my hair so it spurts off the top of my head. Raul and his seatmate snicker. But not Feelees. She climbs up and plops down beside me, then turns her wide calm face to mine and smiles. That’s when I decide that Phyllis is my best best friend.

At the Christmas pageant, Phyllis is Mary the mother of Jesus, and I'm an angel, cardboard wings slightly askew.

But let's turn to our favorite pets, insects.

We love our Harris Memorial praying mantis in its terrarium.

"See, Feelees,” I point to its spindly arms, “it's praying.” She nods. A pious insect.

The next week, a plumb yellow and black caterpillar appears in the terrarium.

“Kerry!” Feelees urgently, “halika dito, bilis, bilis!”

“Titcher, titcher!” yells Ramon. Kindergarteners scamper towards the terrarium.

The praying mantis slices into the soft caterpillar. It squirms in its goo.

“Kita mo yon!”

“Hoy, Boboy, singiting!” Boboy wiggles past Miriam to get closer to the glass.

“Titcher, titcher,” wails Miriam, “Boboy’s making singiting!”

“Titcher, the praying mantis, kinain niya ang catarpillar!”

We struggle with our first semantic crisis of faith: pray to prey.

But we fight for our place in a world of insects who share our meals, flesh, and homes. Langaw buzz the merienda, umok nestle in our Milo and powdered milk; delicate black lines of langgam bore through birthday cakes. Lamok suck up our blood, leave us with dengue. Our hair is the haven of kuto, and we share our beds with surot. We fear ipis, who prefer dark warm cupboards to our roach hotels. We loathe them without distinction—the little ones, the ones that fly, the speckled tan, the long-whiskered ipis. Our house sweats little piles of filings from anay and bukbok; we find alupihan and its cousin the silverfish under old boxes. Of the salagubang, there are jewel, rhino, stag beetles and marching weevils. Then there is the exotic stick insect, the moving leaf sasuma. Not all insects assault us. Magical alitaptap sparkle around palm fronds like Christmas, the fluttery paru paro bring us spirit messages, kuliglig jazz up muggy nights. And tutubi help me forgive them all.

This Saturday, the Monteclaro clan gathers in our yard. “Lets fly tutubi,” suggests Buster. “Dragonfly,” Feelees translates. We swing back the big green gate of the driveway and head up Wright Street to the field two blocks away. Iridescent green and blue tutubi dive and rise through the kogon grass. We kick at makahiya, which means “shy,” and that’s how it acts. Its' low growing fronds curl closed when you touch them. Feelees’ brother catches a tutubi and ties a string to the tail. He lets it go. It pulls away, rising high til the leash pulls it back. It's like a dog with wings or a living kite. The boys are deft. Soon, tutubi kites buzz over the grass, struggling to get free. We giggle. My blue one pulls, swerving in the air. Suddenly, the string drops. It buzzes off. I pull up the limp string to see the end of its tail. “What will happen to it?” I ask Buster. He’s tying someone else’s tutubi to a string. “It will die,” he says without looking up. He's kind. “Ito, for you,” he’s got iridescent wings between his fingers. The green tail curls. “Hwag na.” He shrugs and hands it to someone else. I gaze at tutubi freely diving in the grass. Only later do I pray that they don’t get caught.

It's Saturday. The Monteclaros are in the province. Johanna and I are bored. "Let's go to our clubhouse!" We have a clubhouse on the second rung of the concrete water tower beside our house. But Scotty's clubhouse is on the third rung, and he tosses a mud ball at us.

OK, we're not interested in the clubhouse anyway.

Johanna sighs, then brightens, “Let’s catch black ants!”

“Yeah!”

We don’t really hate them, but the big black army ants crawl in long columns up trees and through the yard and they’re easy pets: independent, plentiful, and disposable.

Our latest experiment is to see how long the army ants can swim. Johanna gets a metal can and fills it with water at the outside faucet and we set a big rock for the island. It’s easy to find the ants. They crawl up the concrete water tower pilings. We flick them into the water and watch them swim to the edge of the can. We pick them up and set them back on their island.

Boy saunters over to watch from the Monteclaro side of the fence.

“Ssst,” we know he’s there, but we ignore him.

“Ssst!” more insistently. He can’t stand it when we ignore him.

“Ano ba ‘yon?”

“Black ant,” Johanna says noncommittally. Boy already knows, of course, and has a battle plan ready.

“I can win your ant,” he brags in a loud whisper.

He holds out a matchbox, tapping it open just a little to show that it’s full of wriggling hantik—I forgot to mention these—the evilest red ants. We check his fingers for hantik stings.

A surge of team spirit wells up. “Sige, war!” I cry.

Jo and I lug the tin can over to the fence. We try not to slurp the water. Boy is supposed to be on some errand or a house job, so he can’t come over. He glances over his shoulder to check the house. We won’t tell.

Boy can’t wait to unload his red army onto the rock island, a surprise attack on our black navy seals. The red ants look fierce. I feel a sudden surge of motherly worry about our insects, but it's too late to back down. The three of us squat by the can, watching the Jackson Pollock tangle of shiny red and black. Boy's hantik, jammed in a matchbox for too long, are ferocious. He clucks at his team like they're fighting cocks, to spur them on. After a while, it’s hard to tell which color is winning. It’s a gruesome battle of dismemberment. Body sections writhe without heads, legs.

We sit in silence until the last red ant is taken down.

“YEY!” Johanna and I jump up and dance, more relieved than jubilant. Boy laughs too. He’s an easy loser. After the hantik war, we treat our black ants with more respect. But I don’t want to play that ever again.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed