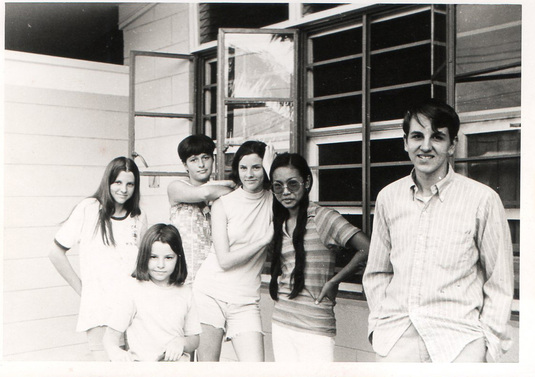

We had our favorites like the Millenburg boys, but of our generation, the A/B+ families lived in Cebu, Davao, Diliman, and Dumaguete. They were mostly blond for some reason. I adored the wave of American "Frontier Interns" --- church-related college grads who arrived to work in community centers, housing, assignments similar to the Peace Corps. Aunty Soli called the Peace Corps, "mga paa ng Americano" (American feet, but not in a nice way), so maybe they were the kamay (hands).

Johanna and I were closest to the M. girls though they lived far south in Mindanao and were more evangelical on the face of it. It was K (she told me I couldn't use her name) who updated us on the revolutionary shift from sanitary pads to tampons.

“Something you stick Up There!”

“Aray!”

“How do they look?”

“White sticks, here, kita mo," She digs in her bag for show and tell. "And you can go swimming.”

We were nowhere near a pool.

I admired their nonchalance about their bodies, which we attributed to their Norwegian mother raised in China. She was holy, a hedonist, and an unabashed socialist. Their father was lanky with a wry sense of humor. I envied them their parents since ours were so modest. The fusion granted them high marks, and though Jo and I were hip Manila girls, K. got extra points for sending us into sheer silliness.

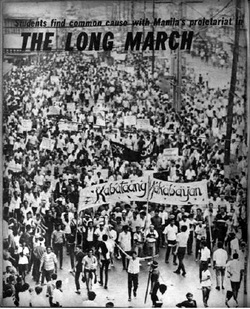

We dealt the lowest ranking to those who attended Faith Academy, Brent, or American school. There were so many private parochial schools in the Philippines and medium of instruction was English. Why go to schools where American kids could cluster? The American school in Makati was geared to business kids and some military brats; few mks attended. I was eventually one of the casualties, but ignored this contradiction. We never visited Faith Academy, and based our evidence on the mk girl who lived across from us on Basilan who was an emotional wreck. As far as we were concerned, this was a school for pious parents who didn't trust the country they’d come to convert. F.

But you had to succeed in both places, the Philippines and the U.S. It was a trip wire.

It went like this:

“Hey, Jo, remember the R. boys?”

“The guys who were Ifugao?” (raised in the Cordilleras mountains)

“Kinda, bakit?”

“I heard from dad that they got back to the U.S. and bottomed out.”

“Wow, angel angel down you go.”

A for Ifugao, D for American disaster. We figured that Scott, now "Brother Love", was due for a C in the America face-off. Johanna would get an A because she was tall, leggy and matapang, fearless. Me maybe a B, bahala na. Margaret was in 4th grade, so maybe the US would be more kind. We weren't sure about that.

That trip wire; would we make it? Can you avoid the question, "why did you grow up there?"

"Missionary kid" produced such an awkward silence.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed