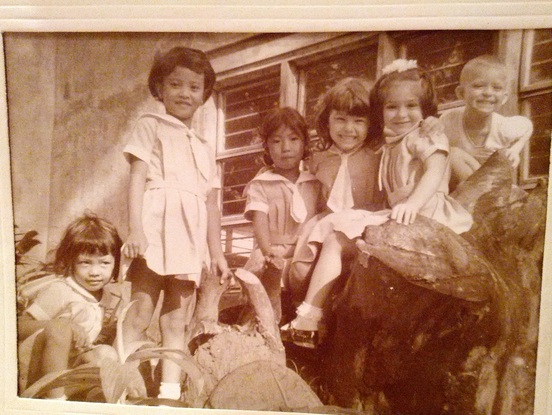

Holy Week 1970, Margaret and the resurrection

Margaret, skirt lifted

Margaret, skirt lifted On Basilan Road, 8-year-old Margaret and 14-year-old me share a bunk in our hippy paisley room. She has the top, I take the bottom and drape a blanket over the opening to make a cave.

Despite the Black Nazarene’s intervention in Quiapo, I’m more interested in levitation and monads at this point in my spiritual journey. We’ve had enough of the Life of Jesus. God tries Margaret on Holy Week, who suffers our teenage whims like a saint.

But Margaret is not a pious kind of saint. She calls the Sunday drive to Ellinwood “the day to be endured” because she gets carsick. This chaotic year, mom hatches an Easter plan that involves a simple breakfast at our house, an Easter “sing-in” and the 10:00 service at Ellinwood. Margaret, much to our surprise, receives parental permission to stay home.

“Aba, pa-bor-a-tism!” wails Johanna who now hates organized religion.

But mom, who is not by nature dictatorial, is General Franco when it comes to Easter and Christmas. Concerned that we hadn’t really absorbed the Easter Story after ten years of Life of Jesus vignettes, she subjects us to a two hour read-aloud from the Bible, from the raising of Lazarus in John through the resurrection. Johanna and I roll our eyes at each other, but we listen obediently.

Eight-year-old Margaret, on the other hand, can’t get her fill of the Passion. On Maundy Thursday and Good Friday, she sits alone through four hours of hokey Passion Week TV movies sponsored by Family Rosary. She watches the whole series again on Saturday.

On Holy Saturday afternoon, a tearful, solemn Margaret comes to mom on the lanai.

“I just saw Jesus going to heaven. Wake me up in the dark so that I don’t miss the Sunrise Service, OK, mom?”

Since our Sunrise Service begins at 6am Mom comes into our room at 5:30 and rustles her.

“Margaret, Margaret, wake up honey. It’s Easter!”

I groan from the bottom bunk, “is it Easter already?”

Margaret leans on one elbow and peers out the window at the light.

“Mom,” she says reproachfully, “It's morning already. I’ve been waiting all night for the morning.”

Margaret’s reproach is hard to bear.

We leave for Ellinwood without her. The rest of the day’s quiet and so is Margaret. At bedtime, I hear mom quietly ask Margaret in the top bunk, “So, Margaret, did you have a nice Easter?”

“Well, to tell the truth, no.”

“Why?”

“It was so simple.” Then she looks away as if ashamed.

“I thought the world would end today.”

Despite the Black Nazarene’s intervention in Quiapo, I’m more interested in levitation and monads at this point in my spiritual journey. We’ve had enough of the Life of Jesus. God tries Margaret on Holy Week, who suffers our teenage whims like a saint.

But Margaret is not a pious kind of saint. She calls the Sunday drive to Ellinwood “the day to be endured” because she gets carsick. This chaotic year, mom hatches an Easter plan that involves a simple breakfast at our house, an Easter “sing-in” and the 10:00 service at Ellinwood. Margaret, much to our surprise, receives parental permission to stay home.

“Aba, pa-bor-a-tism!” wails Johanna who now hates organized religion.

But mom, who is not by nature dictatorial, is General Franco when it comes to Easter and Christmas. Concerned that we hadn’t really absorbed the Easter Story after ten years of Life of Jesus vignettes, she subjects us to a two hour read-aloud from the Bible, from the raising of Lazarus in John through the resurrection. Johanna and I roll our eyes at each other, but we listen obediently.

Eight-year-old Margaret, on the other hand, can’t get her fill of the Passion. On Maundy Thursday and Good Friday, she sits alone through four hours of hokey Passion Week TV movies sponsored by Family Rosary. She watches the whole series again on Saturday.

On Holy Saturday afternoon, a tearful, solemn Margaret comes to mom on the lanai.

“I just saw Jesus going to heaven. Wake me up in the dark so that I don’t miss the Sunrise Service, OK, mom?”

Since our Sunrise Service begins at 6am Mom comes into our room at 5:30 and rustles her.

“Margaret, Margaret, wake up honey. It’s Easter!”

I groan from the bottom bunk, “is it Easter already?”

Margaret leans on one elbow and peers out the window at the light.

“Mom,” she says reproachfully, “It's morning already. I’ve been waiting all night for the morning.”

Margaret’s reproach is hard to bear.

We leave for Ellinwood without her. The rest of the day’s quiet and so is Margaret. At bedtime, I hear mom quietly ask Margaret in the top bunk, “So, Margaret, did you have a nice Easter?”

“Well, to tell the truth, no.”

“Why?”

“It was so simple.” Then she looks away as if ashamed.

“I thought the world would end today.”

Margaret and the Communion of Saints

Maybe because the world didn’t end, Margaret begins to commune with the dead. I understand; it’s a predictable path, but Margaret isn’t divulging this to me, even though we’re bunkmates. Teen-dom is such a self-obsessed condition and I am contemplating my own death, so there's no space for anyone else's.

Margaret commits mom to secrecy (which obviously mom betrays because I’m writing about it).

"Can the dead can see and hear us?"

Of course, we know the answer is yes, but mom hedges.

"Why, do you think so?"

Margaret confides, “After I say my prayers with you at night I talk to dead people.”

A chill runs down mom’s spine. “Who?”

“Grandmother Henrietta, and your daddy, and Auntie Eva (she met her in Hawaii last June). Other people too.”

She hesitates; here’s the question she’s wanted to ask.

“Do dead people hear only us or do they hear everyone at the same time, like God?”

“I don’t know, Margaret.”

Later, mom asks Rev. Dario Alampay, the pastor of Ellinwood and a good friend.

He muses, “Lots of people today don’t like to talk about ‘unseen’ life. It’s supposed to be superstitious. But what does the ‘Communion of the Saints’ mean and what does it mean when we say Christ is Lord of the living and the dead, if we don’t mean what Margaret is talking about.”

My little sister talks with the spirits in the bunk above, and I am consoled by them in the bunk below.

Margaret commits mom to secrecy (which obviously mom betrays because I’m writing about it).

"Can the dead can see and hear us?"

Of course, we know the answer is yes, but mom hedges.

"Why, do you think so?"

Margaret confides, “After I say my prayers with you at night I talk to dead people.”

A chill runs down mom’s spine. “Who?”

“Grandmother Henrietta, and your daddy, and Auntie Eva (she met her in Hawaii last June). Other people too.”

She hesitates; here’s the question she’s wanted to ask.

“Do dead people hear only us or do they hear everyone at the same time, like God?”

“I don’t know, Margaret.”

Later, mom asks Rev. Dario Alampay, the pastor of Ellinwood and a good friend.

He muses, “Lots of people today don’t like to talk about ‘unseen’ life. It’s supposed to be superstitious. But what does the ‘Communion of the Saints’ mean and what does it mean when we say Christ is Lord of the living and the dead, if we don’t mean what Margaret is talking about.”

My little sister talks with the spirits in the bunk above, and I am consoled by them in the bunk below.

"We should be free"

In July, Margaret has a vision.

She steals quietly into the sala and declares in an 8-year-old shy, matter of fact voice,

“I just saw Jesus in white lines.”

Mom tries to hide her surprise (of the mind that God doesn’t actually visit).

“Where were you?”

“On the lanai.”

“What were you doing?”

“Playing Barbie dolls. I saw Jesus in white lines.” She draws the outline of a figure in the air.

“How do you know it was Jesus?”

Margaret eyes mom with incredulity.

“Who else would come down from heaven?”

“Were the white lines like a drawing or a photograph?”

“Like a photograph. Does it mean the world is coming to an end?”

“No... I don’t think so.”

“It would be better if it did. Then I wouldn’t have to die.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, I would be with God right away. I wouldn’t have to suffer and all that."

She hesitates. "I would be free. We’d all be free.”

Some time later, mom wakes from a siesta with a picture laid neatly on her stomach. Margaret’s rendition of a family: dad fishing, mom carrying a basket (of laundry?), children playing under the trees. It might have been a log cabin in the woods. She'd written, “Why can’t we live the way we want to live, like this.”

The next day, mom asks her about the picture.

“I wish we didn’t have rules. We should be free.”

I wonder what Margaret in the middle of her life as a creative, trouble-shooter, rule-abiding agnostic makes of this now, her religious year burdened by God and longing to be "free."

She steals quietly into the sala and declares in an 8-year-old shy, matter of fact voice,

“I just saw Jesus in white lines.”

Mom tries to hide her surprise (of the mind that God doesn’t actually visit).

“Where were you?”

“On the lanai.”

“What were you doing?”

“Playing Barbie dolls. I saw Jesus in white lines.” She draws the outline of a figure in the air.

“How do you know it was Jesus?”

Margaret eyes mom with incredulity.

“Who else would come down from heaven?”

“Were the white lines like a drawing or a photograph?”

“Like a photograph. Does it mean the world is coming to an end?”

“No... I don’t think so.”

“It would be better if it did. Then I wouldn’t have to die.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, I would be with God right away. I wouldn’t have to suffer and all that."

She hesitates. "I would be free. We’d all be free.”

Some time later, mom wakes from a siesta with a picture laid neatly on her stomach. Margaret’s rendition of a family: dad fishing, mom carrying a basket (of laundry?), children playing under the trees. It might have been a log cabin in the woods. She'd written, “Why can’t we live the way we want to live, like this.”

The next day, mom asks her about the picture.

“I wish we didn’t have rules. We should be free.”

I wonder what Margaret in the middle of her life as a creative, trouble-shooter, rule-abiding agnostic makes of this now, her religious year burdened by God and longing to be "free."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed