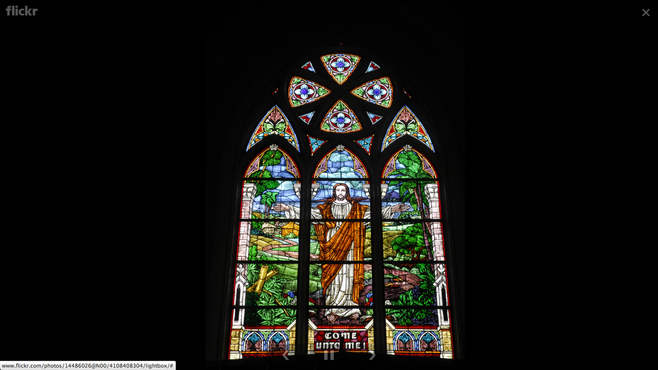

The Orange Jesus seems impervious to suffering. He isn’t hangdog with a crown of thorns, or butchered on a cross, or holding his bloody heart, or slumped on his mother’s lap. And he’s not even sweaty in all those clothes. He’s pale and unscarred, with a mild “don’t worry” expression. He visits me in my sleep, or when I wake in the middle of the night, or when I pray that I’ll find something I lost before daddy knows I lost it. Orange Jesus appears shimmery and see-through. His voice has the timber of all the voices I know melted together. When he comes, I feel quiet with relief. “Come unto me,” he says. But he never says where we are going.

I love Orange Jesus with his arms wide open. “I am with you always, even to the end of time,” says Rev. Geconcillo quoting Jesus. Everyone says he is with us everywhere, which you have to wonder about, since there is only one of him and lots of us. And grandmother in the States, is he with her when she’s cooking candied orange peels for us at the same time I’m going down the water slide? Is he only with people? How about the maya birds that scatter around us, and Melting Snow our outside cat, or camias and avocado trees?

Does the Orange Jesus like to play Tarzan vine with us? The acacia rustles gently in response.

“Ssst,” Boy calls. I get up from the carabao grass, brushing off little bugs, and wander over to the crooked wire fence that separates our compound from the rambling old house where the Monteclaros live.

“Halaka,” he hisses once he has my full attention,

“Seguro may diwata sa acacia mo.”

Boy has a buzz cut, a long face with hollow cheeks. We don’t know how old he is because he doesn’t go to school. He says his uncle flew to the States by holding onto the wheels of the plane. His eyes get big in his thin face when he’s telling these things. Sometimes we’re a little afraid of him.

I look at him quizzically. I thought diwata only live in balete trees. The spirits cajole you into visiting them and then don't let you go home. Are they in acacias too? At first I don’t mind, but then I feel them buzzing. It's not the sound of a cloud of saints or angels, who make little tingting sounds.

Daddy has an office on the ground floor that opens out into the yard.

I open the screen door and stick my head in.

“Daddy,” I say carefully, not to worry him.

“Yes Kerry,” he doesn’t look up.

I edge in. We’re not supposed to bother him in his office unless it’s important.

“Daddy, Boy ses dere's spirits in da acacia.”

There’s a brief silence.

He looks up and the light bounces off his black framed glasses. Now he is a pastor, not just my father.

“No Kerry, there aren’t spirits in trees.”

It’s a gentle answer, but it’s final.

“OK,” I close his screen door slowly and turn to the big tarzan tree.

How am I going to avoid them?

It’s a gentle tree, really. Would Orange Jesus pull me out? I gingerly scratch its bark and frondy leaves rustle as though they are purring. Small ants, itchy worms, and grimy bugs nestle in its yellow fuzz flowers. It’s not tidy. But it doesn’t fuss when we climb up to its paunch and swing on the Tarzan vine. I squat on the edge of our cement walk and send the acacia a single thought: “If you love me, don’t let them take me.”

But I wonder. When Orange Jesus says, “Come unto me,” does he also mean the acacia's diwatas? Are diwatas afraid of him because he'd chase them out? Where do the diwata live if they don’t have a treehouse? Doesn’t Orange Jesus also love diwatas? Maybe they’re just in a bad mood because they were here first. Why is there a war between their nations? Why can’t diwata and Orange Jesus like each other and share the tree?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed