Johanna’s a scamp. When she's little, she’s already suspicious of the Sacraments. We're kicking our feet aimlessly into the air, skewered one-two-three between mom and dad on the hard wooden pews. Dad hands mom the Communion bread over us. Johanna's hand shoots out for a little white square of Wonder Bread. Mom catches her wrist. Jo pulls at squirms, “I’m hangry!’

Mom whispers, “Not this bread Johanna, you can have a popsicle after church.”

Then the big silver tray with little glasses of grape juice is passed over us and continues down the pew.

Mom and dad each take one, swig them, and set them in little holes in back of the front pew.

I like those little holes.

Mom leans over with her head in her hands.

This alarms Johanna. "Whattsa matter?”

When mom still doesn’t answer, Johanna tries again, “Whattsa matter mommy, koolaid feel you bad?” A fit of giggles ripples down the pew.

When she’s older, Johanna doesn’t even sit with us. She slips up to the balcony to draw.

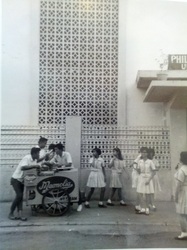

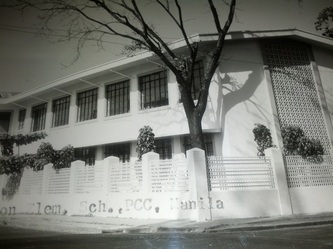

But Sunday tops the charts. First, there’s Sunday School, which we love, no lie. If we have to go to church too, then after the choir sings “Amen, Amen, AAaaaaa-men,” we tumble out with a crowd that congeal on the outside of the church to greet each other. The popsicle men position their carts at the gutter beside the sidewalk. “Chocolate!” Our popsicle man lifts up the metal cover and dry ice smoke billows into the muggy Sunday heat. Chocolate is best, then orange, last pineapple. If we wheedle, he might break off a bit of dry ice so we can pretend smoke or play Brigadoon, the ghost island.

Mom and dad invite foreigners visiting Ellinwood, so we never know who is coming to Sunday Dinner. Mom sets out her Irish lace tablecloth. Once a week, we get frozen fruit salad dissolving in 7up, and scoop out the cold fruit with Thai brass spoons that grandmother brought us. Our favorite aromas waft from the kitchen - breaded pork, steak Dianne or crisp fried chicken. Always, always white rice and green beans.

The grand feast of Sunday dinner is followed by the sacred lull of an afternoon of Rest Time, which mostly means mom can take time off until Sunday pizza, which she smothers with thick tomato paste, Vienna sausages, and Velveeta. We eat the pizza to drink Coke, our weekly ration. And the ultimate reward. We don't sing or pray, and we eat in front of the TV in the Airconditioned Room, watching Bonanza where we travel through the burning map to the Ponderosa. We munch, swig, and live Out West with the Cartwrights and Hop Sing. Then dad pats us out of The Airconditioned Room so he can watch The Fugitive, which we figure is x-rated since we never get to see it.

When we are teenagers, mom and Auntie Eva publish the thin red Filipino Family Cookbook with recipes from the SS Wright maternal mafia. By then, we've tested them against American versions, but none can compare to Sunday pizza on 1667 B Wright Street.

Quick pizza dough

1/4 cup warm water 1/2 cup cold water

21/2 tsp dry yeast 3 cups sifted flour

1 tsp sugar 1 tsp salt

1/4 cup boiling water 1 tbsp sugar

2 tbsp shortening

Dissolve 1 tsp sugar in 1/4 cup warm water. Sprinkle the yeast in slowly. Stir gently to dissolve. Set aside. Dissolve shortening in 1/4 cup of boiling water. Add cold water and cool to lukewarm. Add yeast mixture. Beat in sifted flour, salt, and 1 tbsp sugar. When blended let stand for 15 minutes. Divide into two parts. Flatten into pancakes and press to form 12” circles. Use pizza pans or cookie sheets. Brush with olive oil and add filling given below. Bake 12-20 minutes at 450 F.

Filling

4 tbsp cooking oil chopped onions

green pepper 2 cups Vienna sausage

garlic 1 can tomato sauce

salt black or green olives

shredded cheese anchovy fillets

bay leaf pepper to taste

Vignettes of Christmas, 1965

Eunice Poethig to Juliet Blanchard

Snow on Christmas Eve is a glorious event. This hard rain would have been a real snow blizzard, making streets slippery, sending the children to the closets for snow suits, turning even ordinary shrubs into Christmas trees.

But rain on Christmas Eve wets the poinsettias blooming high by the fence. After the rain stops, children’s gowns must be carried to the church and the elaborate preparations for the crèche in the chancel viewed. Tonight is the Carol Service.

It’s 7:00pm. The children are gowned and seated in their risers behind the crèche. The lighting is lovely. Lilies Kapili hasn’t arrived yet! The adult choir is straggling in. I can’t get choir gowns for the candlebearers because she has the key to the cabinet.

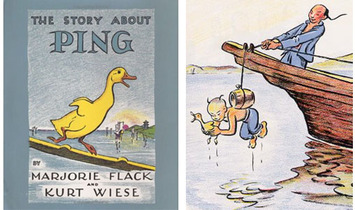

The Carol Service is not going as well as dress rehearsal. But my “angels!” Scott, Kerry and Johanna are singing their hearts out. They look wonderful. Scott still has a choir-boy look. It’s his last year with it, probably. Kerry looks so pure, and Johanna’s long blond hair shines in the light. Johanna has a solo and she did it very well. The three of them, joined by Loius Panlilio are singing a two-part song. Margaret is supposed to sing the first verse alone. Slight mix up and she didn’t start off on the right note so all join her, then on the second verse (which she doesn’t know), Louie handed her a book so she could “read the words.” She’s 3.

10:00 pm. Christmas Eve. Present giving has never been more of a family affair. We have laughed over Johanna’s cleverly wrapped presents – a belt for school wrapped like a wreath, a charm for Kerry baked in a roll. Kerry’s red rubber gloves for me were this year’s example of her tradition of surprising gifts. Cresing and Annie thought the electric toothbrush for her was hilarious. There weren’t so many presents that theirs were insignificant. Only Margaret was deluged. She also gave presents to everyone – of her own choosing: toothbrushes and toothpaste for Scott, daddy and Johanna. Paints for Kerry, pencil sharpeners for Annie and Cresing, Scotch tape for me. They added to the merriment. I gave Dick paper mache wise men, and he gave me a box of special cookies that he loves. It was an Eve in which the mood was not magic but pleasure.

10:30pm Christmas Eve David Baradas and Dorothy Cleveland, a PCV friend arrive. The children sing for them. We all east stolen, ham sandwiches and Coke. Coke because it is hot tonight. It is good to hear about the adventures of a beginning anthropologist. We remember the Christmas together in Dayton. The outer trimmings are different, but their very differentness is the thread that holds our lives together.

CHRISTMAS DAY

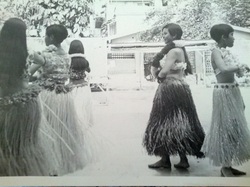

We’re on our way to Baguio. I’m glad we chose to drive today. Without family to visit, there is not much to do on Christmas Day. Traffic is light. Families are out to visit. The children are so pretty in their colorful new clothes. That fairyland of dresses in Central Market has reached the streets.

Baguio has its own Christmas magic. In one day we have combined the gaiety, fun and sociability of a Philippine Christmas with the cosyness and intimacy of an American Christmas Dinner at Camp John Hay, which was turkey, mince pie, and apples. A rug on the floor, a formal white cloth on the table. There are stories and carols and prayers together in our snug cottages surrounded by silent pines.

THE DAY AFTER

I am tired. I’ve celebrated more fully than usual because it has been a shared celebration with many people. For the fist time it has not been a Christmas I’ve received or one I have given to others. It has been shared with the children in their own Christmas activities, shared with the church in its preparations, shared with friends in carols, parties, gifts, shared with our family in a host of preparations. I’m ready now to just be alone.

LATER

This year we’ve had two styles of Christmas. Other years, since I more or less controlled the celebrations, we tried to duplicate the mood of Christmases we knew.

The problem seemed to be how to capture the mood of magic, surprise, and silence that are essential to an American Christmas. There’s no hope of having those things in Manila! And we didn’t. We had a Philippine Christmas with its mood of fun, friendly gift exchange throughout the season, song and sociability. I don’t know what it has to do with the birth of Christ, but it’s good for the heart.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed