Orange Jesus whispers with the acacias, “If it’s not magic, don’t believe.”

This is our secret pact.

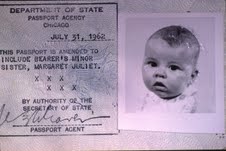

Easter Sunrise Service

Ellinwood church, but it's a place holder.

Ellinwood church, but it's a place holder. ---

We were UCCP but everything untamed and unpredictable was Catholic. The Catholics, for example, were better prepared for spirit assault. They were armed with garlic, red crosses on the threshold, holy water and crucifixes to protect against “elemental spirits” such as dwendes, engkantos, diwatas, and the most despicable– aswang. Aswang bloodsuckers are half-bodied creatures that appear as beautiful virgins by day. You don’t grow out of the fear, just learn when to sleep with the rosary under your pillow. Later, when I'm living in Bataan in Morong by the sea, my little nipa house is a nest for aswang. Aling Fanny, my cook and a devout Salvation Army sergeant sings gospel songs aloud to keep them away. She hangs a lime green glow-in-the-dark rosary from the bare bulb in the kitchen, but it scares the bejesus out of me when I stumble to the bathroom after midnight – right into the luminous noose.

Our retort to the spiritual paraphernalia the Catholics? Protestants could repel spirits with words from the Bible or sheer faith in Jesus. Though my parents didn’t engage in this kind of talk, it still worried me. Our main fallback was The Resurrection. Protestants Believed in The Resurrection. Catholics fixed their attention on The Crucifixion.

“The dead you will have always,” I claim confidently.

It's fifth grade Religion class at our Protestant parochial school.

“KerRY!" from the back of the room, "The poor you will have wit you always.”

“Well, the dead too,” I say defensively, “until the resurrection.”

But it did seem like the dead were with us always. One coffin replaced another in the small chapel to the left of the Ellinwood sanctuary. Wake upon wake, flocks of black clad families grieved in silence, ate meals in the pews. The chapel reeked with a mixture of formaldehyde, lilies, and someone’s ba-on, snacks for the wake. Strange men stepped out to smoke in silence. Our curiosity was incurable. One after another, our little barkada would shuffle up to peer in the open coffin. In Manila heat, the corpses looked uncomfortable, purple, puffy and caked with makeup. We shuffled out, and then ran away, only to come back for the next one. Why did they "suffer the children," I wonder now.

What did it mean, that Jesus conquered death?

Take Mrs. Castaneda, she was a model of resurrection life. When her husband passed away, our elementary school arrived en masse to the memorial service since she was a favorite among the other faculty. Instead of black dress and veil, she wore white, her face so aglow we knew she’d been talking with Jesus.

“Kita mo - bride ob Christ!” whispers one of my classmates. We hear that some teachers were scandalized, but that she said,

“My husband has eternal life. We will meet again at the resurrection.”

I thought we met again after we died. Did we have to wait till the resurrection?

We had a discussion about the resurrection in Miss Juaquin in Religion class.

“The dead shall be raised in the last days and divided, wheat from chaff,” our teacher reads a relevant passage. (We know how farmers sift palay from rice grain. It whirls away in the wind).

“What kind of bodies do we have at the resurrection?” That's Nelson, the smart one.

“Immortal bodies.”

“The resurrection!” drones Reuel, clowning. We giggle.

Miss Juaquin stiffens. “Immortal bodies, class. Immortal.

She stops for emphasis.

“Remember Jesus meeting Mary Magdalene at the tomb?”

We know that Easter story by heart. Mary Magdalene is weeping in the garden by the empty tomb. Jesus (all shimmery like my Orange Jesus) shows up, she thinks he’s the gardener. He says something to throw her off, “woman who are you looking for,” and she sniffles, wiping her nose, “Sir if you have taken him away, tell me where you have laid him.” Then he just says “Mary!” (He could see she was messed up.) All she can get out is “Rabboni!” Then he says “Do not touch me till I go to your father and mine.” What would happen if she touched him, don’t you wonder?

It’s so romantic, Orange Jesus and Easter.

Anyway, for Protestants Jesus’ resurrection is Most Important. This is why, explains mom, our crosses are empty, and we don’t self-flagelle or hold mock crucifixions. We get sad when Jesus dies on the cross with the last of the Seven Last Words, ‘Into Your Hands I commend my Spirit,” but we limit our mourning to Good Friday afternoon, since Jesus died at 3pm.

The entire country mourned the death of Jesus on Holy Saturday. No one was supposed to travel except for night processions, where you could walk solemnly (or chat with each other) behind a statue, rumbling along with the prayer on the loudspeaker. The younger women were beautiful in their lace mantillas and white candles. That was a Catholic plus.

Ah Easter! Our great day! Especially if you belong to the SS Wright, our Ellinwood church Schooner group. A dozen firm and feisty "Aunties/Titas" feed, discipline our general silliness, and instruct us in music, the performing arts, and a generous interpretation of the bible. I'm especially fond of Auntie Eva, Auntie Joy, and my second mother, Auntie Soli mother of Luna, best friend from high school onward, and Butch, my carinoso bro. The dozen "Uncle/Titos" support their wives in genial good cheer, pack the car, and drive us on our excursions.

So, Easter is the main SS Wright annual event.

In the early morning dark, “Wake up Kerry…Kerry, Kerry, wake up.” So groggy, thick with sleep. We dress without turning on too many lights to keep the effect, and stumble to the Chevy packed with food, props, hand-sewn costumes and hymnals. In elementary school, we drive forty-five minutes to the cool hills of Antipolo where the Niguidulas have a house near hills with a rolling back yard. By the time we’re in High School, the parents discover UP Balara in Diliman, which is closer and has a covered picnic pavilion near an ivy-lined stone wall, essential as a backdrop for The Resurrection pageant.

We can watch us grow up through slide shows these pageants. Jesus is 10 year old George Padolina, then my brother, then Glenn Jainga. By high school, Lyncir and Clyde are the disciples coming up from the beach. This morning, in the dark at UP Balara, Leslie Villanueva plays Jesus. Tita Joy lines up the Roman soldiers costumed with brown plastic flaps over a red shirt and shorts. She hands Dario his aluminum foil helmet just before they march to arrest Jesus.

“Judas would you betray me with a kiss?” Jesus/Leslie asks Judas who in no way is going to kiss Leslie.

Tita Joy is an actress in real life, so she directs this Easter story, but we’re on our tenth annual Resurrection and the actors all know their blocking. Mostly they improvise. When Peter tries to chop off the ear of the high priest, Jesus gives Peter a Kung Fu hand chop. Peter whips round to Kung Fu Jesus. This causes the Roman soldiers to cheer. We skip the crucifixion and go directly to Easter. Enter Mary in her blue toga and veil. Mary is usually played by Erlyn or Nene Bernardez since they’re future beauty queens. This time, it’s Erlyn who gracefully sets out with terra cotta pot on her shoulder to the Balara stone wall which is Jesus’ tomb. She peers in dramatically, and holds for a moment. After a bit of sst-ing the angel appears from behind the ivy wall. He’s one of the seven de la Calzada boys. He leans on one arm against the wall, “Wala tao dito, Mer.” The parents chuckle. Then Leslie-Jesus, promptly appears and Erlyn-Mary drops gratefully to her knees, “Sir if you have taken him away, tell me where you have laid him.”

Leslie-Jesus right palm down, left hand up, “Mary!”

Erlyn gesturing slightly towards his leg, “Rabboni!”

Leslie, right palm out, “Do not touch me till I go to your father and mine.”

It’s almost like Romeo and Juliet.

Leslie slips behind the stone wall and Mary runs Stage Right to Peter, who throws out his arms like ‘Say what?!” He beckons to a buddy and they run Stage Left, peek behind the ivy wall, big shrugs to the audience, wave their hands around and the play is over. The Resurrection! Mom and Tita Joy lead us in “Crown him with many crowns, the Lamb upon His throne!” and “Alleluja!” Someone picks up the guitar and strums off key before finding the tune.

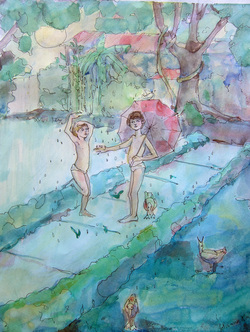

The sun pushes up through the thick overgrowth, palms and acacias at UP Balara in an excited sort of way, blushing orange and pink. It’s 7am and getting hot, so the littler kids are set loose to find the hard boiled Easter eggs we’ve hidden in the dark –fuchsia, baby blue, paisley swirls, magenta with yellow dots. Now the wooden picnic tables are crammed with potluck breakfast. Our mothers have brought Nescafe and evaporated milk, mangoes cut into patterns, fruit salad, suman (sticky rice wrapped in banana leaf), pandesal, the paisley Easter eggs, rice and dried fish, Vienna sausages, Coke, ensamada. It’s a pandemonium of feasting. The Orange Jesus is particularly happy this morning, and this sends a little tingle of joy through me. Lyncir, our pogi activist has picked up the guitar so we’ll sing all morning. I lick mango juice off my fingers and crack open a prize egg – green with pink and fushia daisies. The real resurrection must be something like this.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed