Haiku of our tour of Japan

Point to plastic food in the Tokyo glass case,

Noodles but no spaghetti

So Scott won’t eat.

Bob Fukada talks as he takes us to the red Zen temple

A friendly American sound

from a brown Presbyterian.

Mom buys a silk kimono in Kyoto

In the back, a tea house and pool

Where we feed golden carp our fingers.

Point to plastic food in the Tokyo glass case,

Noodles but no spaghetti

So Scott won’t eat.

Bob Fukada talks as he takes us to the red Zen temple

A friendly American sound

from a brown Presbyterian.

Mom buys a silk kimono in Kyoto

In the back, a tea house and pool

Where we feed golden carp our fingers.

Stony Point, New York

After five years in Manila, we have a Furlough, which means we live in America for a year. Scott will go to third grade, I’ll be in first grade and Johanna in kindergarten. Little baby Margaret joins the family.

That year we live at the Presbyterian Church’s Stony Point conference center in New York on the second floor of a stone house with the window seats. An Indian family with two teenage girls lives downstairs. Their house is dark, dark, dark. It emits misery. Dad will stay an hour away in New York City. He’ll be getting a MA at Union seminary (he already has an M.Div from Union, where he met mom), and has job with the Urban Africa Project. “Why isn’t he living with us?” we want to know. “It’s too far,” says dad. We know far. Manila is far.

We meet our relatives. We have one grandmother (mom's mother), one grandfather (dad's father), one aunt (dad) and uncle (mom), six cousins and various in-law relations, first cousins twice removed and so on. Grandmother Juliet Blanchard lives on Adirondack Trail, Dayton, Ohio in a beautiful stone house. The ghost in grandmother's house is our grandfather Pete Blanchard who died in an airplane crash when mom was in college. It's a long story and we don't learn about it til we're much older.

On the Poethig side, we visit Aunt Erna, Uncle Tim, our six boy cousins and grandfather Poethig in New Jersey. Uncle Tim is Catholic, so Aunt Erna is a Catholic. Our grandfather Ernest Poethig sits on a couch with dad. He doesn’t say much. When Aunt Erna brings out old b&w pictures, we laugh at grandmother Henrietta in a grass skirt, she's crossed her long legs and is playing a ukulele. She died of TB when dad was nineteen. Grandfather rustles around for the picture of him and Henrietta on their tenement rooftop. Dad’s smile eases and grandfather pats him on the leg. They don’t look at each other, but they’re both smiling so we can relax. Then we have a real American picnic with hamburgers, potato chips, and lemonade with our cousins and their New Jersey accents.

In America, schools start in September instead of June. We buy school supplies but something's missing.

“Mommy, mommy, what about uniforms!”

“No uniforms, Kerry.”

No uniforms? How will they know what school we belong to? If we get lost, how can they find us? My fear is a premonition.

We will ride a yellow bus. On the first day of school mom drives us to the big elementary school. But the next day, she escorts us to the yellow bus spot near Gilmore Sloan house.

“Remember to tell the driver, Gilmore Sloan,” she reminds us.

"Yeah, yeah," says Scott, who is a little scared, but he doesn't want to show it.

Then, it’s 3pm and corridors are packed with kids scampering out to the parking lot. I can't find Scott, but see Johanna running from her kindergarten room near mine. We stand together, holding hands as all the buses leave. When the lot is almost empty, I burst into tears. It’s like Ping, the last yellow duck on the Yangsee River.

A lone bus drives up to us. “Where to, kids?” asks the driver kindly. I sob while Johanna says loudly,

“Geelmore Slon, Geelmore Slon!” He nods and takes us to the place where little kids have accents.

In First Grade, we each have a chair and a desk. You pull up the top and hide things, like extra ba-on, pencils, and school books. We have worksheets to fill out, but mostly I like to collect them: rich thick white paper with purple mimeo ink. I sniff secretly. America smells like mimeo and Baguio pine. It smells chemical and in the Spring cold wet green grass.

“See Spot run.” Spot is a dog, and Sally has yellow hair. I steal a glance at the colorful hair of my classmates. They remind me of home: mahogany like our floor, bright yellow like ducklings, light brown like cuchinta. Phyllis has shiny black hair like everyone else: black hair, brown skin, dark shiny eyes. I want to go home.

The school nurse calls mom.

"Mrs. Poethig, could you visit me at the clinic."

She stands in her white starched uniform at the door and greets mom nervously.

“I have a few concerns about one your children’s medication,” she taps the form gently with a pencil.

“What seems to be the problem?" mom's alarmed. We're sick all the time in the States - measles, mumps, tonsels out, bad sniffling colds. What else can we get?

“That’s what you give dogs for worms” she points to a medication form, embarrassed for mom.

“Oh, it’s only about worms!” my mother drops back her head and laughs.

This is what we learn about America. It smells chemical but you still get sick. Since American kids don’t have yayas, they can run wild. No one thinks we’re rich, so Johanna and I can sell lemonade. We are kind of American, kind of not.

After five years in Manila, we have a Furlough, which means we live in America for a year. Scott will go to third grade, I’ll be in first grade and Johanna in kindergarten. Little baby Margaret joins the family.

That year we live at the Presbyterian Church’s Stony Point conference center in New York on the second floor of a stone house with the window seats. An Indian family with two teenage girls lives downstairs. Their house is dark, dark, dark. It emits misery. Dad will stay an hour away in New York City. He’ll be getting a MA at Union seminary (he already has an M.Div from Union, where he met mom), and has job with the Urban Africa Project. “Why isn’t he living with us?” we want to know. “It’s too far,” says dad. We know far. Manila is far.

We meet our relatives. We have one grandmother (mom's mother), one grandfather (dad's father), one aunt (dad) and uncle (mom), six cousins and various in-law relations, first cousins twice removed and so on. Grandmother Juliet Blanchard lives on Adirondack Trail, Dayton, Ohio in a beautiful stone house. The ghost in grandmother's house is our grandfather Pete Blanchard who died in an airplane crash when mom was in college. It's a long story and we don't learn about it til we're much older.

On the Poethig side, we visit Aunt Erna, Uncle Tim, our six boy cousins and grandfather Poethig in New Jersey. Uncle Tim is Catholic, so Aunt Erna is a Catholic. Our grandfather Ernest Poethig sits on a couch with dad. He doesn’t say much. When Aunt Erna brings out old b&w pictures, we laugh at grandmother Henrietta in a grass skirt, she's crossed her long legs and is playing a ukulele. She died of TB when dad was nineteen. Grandfather rustles around for the picture of him and Henrietta on their tenement rooftop. Dad’s smile eases and grandfather pats him on the leg. They don’t look at each other, but they’re both smiling so we can relax. Then we have a real American picnic with hamburgers, potato chips, and lemonade with our cousins and their New Jersey accents.

In America, schools start in September instead of June. We buy school supplies but something's missing.

“Mommy, mommy, what about uniforms!”

“No uniforms, Kerry.”

No uniforms? How will they know what school we belong to? If we get lost, how can they find us? My fear is a premonition.

We will ride a yellow bus. On the first day of school mom drives us to the big elementary school. But the next day, she escorts us to the yellow bus spot near Gilmore Sloan house.

“Remember to tell the driver, Gilmore Sloan,” she reminds us.

"Yeah, yeah," says Scott, who is a little scared, but he doesn't want to show it.

Then, it’s 3pm and corridors are packed with kids scampering out to the parking lot. I can't find Scott, but see Johanna running from her kindergarten room near mine. We stand together, holding hands as all the buses leave. When the lot is almost empty, I burst into tears. It’s like Ping, the last yellow duck on the Yangsee River.

A lone bus drives up to us. “Where to, kids?” asks the driver kindly. I sob while Johanna says loudly,

“Geelmore Slon, Geelmore Slon!” He nods and takes us to the place where little kids have accents.

In First Grade, we each have a chair and a desk. You pull up the top and hide things, like extra ba-on, pencils, and school books. We have worksheets to fill out, but mostly I like to collect them: rich thick white paper with purple mimeo ink. I sniff secretly. America smells like mimeo and Baguio pine. It smells chemical and in the Spring cold wet green grass.

“See Spot run.” Spot is a dog, and Sally has yellow hair. I steal a glance at the colorful hair of my classmates. They remind me of home: mahogany like our floor, bright yellow like ducklings, light brown like cuchinta. Phyllis has shiny black hair like everyone else: black hair, brown skin, dark shiny eyes. I want to go home.

The school nurse calls mom.

"Mrs. Poethig, could you visit me at the clinic."

She stands in her white starched uniform at the door and greets mom nervously.

“I have a few concerns about one your children’s medication,” she taps the form gently with a pencil.

“What seems to be the problem?" mom's alarmed. We're sick all the time in the States - measles, mumps, tonsels out, bad sniffling colds. What else can we get?

“That’s what you give dogs for worms” she points to a medication form, embarrassed for mom.

“Oh, it’s only about worms!” my mother drops back her head and laughs.

This is what we learn about America. It smells chemical but you still get sick. Since American kids don’t have yayas, they can run wild. No one thinks we’re rich, so Johanna and I can sell lemonade. We are kind of American, kind of not.

Margaret is born

Snow! “It’s like being inside the refrigerator!” We make a snowman, and mom makes us wear jumpsuits. We take the train to grandmother’s house for a real Christmas. "Over the river and through the woods, to grandmother's house we go...." Grandmother’s house has a old house smell you can't ever explain, but it's my favorite smell of America. Our hearts are sweet with the magic of being together in the cold. Mom is especially keen to celebrate Jesus' birth in the winter. She and grandmother are mistresses of high tradition. We play in the snow drifts and then stomp off the snow to deck a piney Christmas tree with olden ornaments. Grandmother builds a log fire that crackles while we sip hot cidery wassail. On Christmas morning, the adults go room to room singing "Merry merry Christmas everywhere, cheerily it rings out in the air, Christmas bells, Christmas trees, Christmas odors on the breeze." We run downstairs in our flannel pjs.Breakfast is fresh baked stollen and scrambled eggs. We open presents one by one. So it doesn't really matter that during Christmas we first get mumps and then measles.

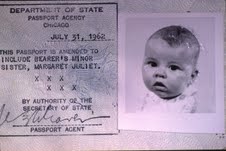

I don't remember when mom tells us we are getting another brother or sister. She gets bigger and bigger. In March, as the ground starts balding and yellow daffodils poke courageously up from the snow, Margaret Juliet arrives. Dad drives grandmother’s Oldsmobile with mom holding a soft white bundle like baby Jesus. We clank pots and pans around the car. “Sssh,” says dad happily, “your new sister’s sleeping.” She curls in a big white bassinette covered with a white veil. Mom brings back flowers in a pretty blue jay vase.

“Can I hold her?”

“Only if you’re sitting on the couch,” mom passes her to me. Johanna and I sniff our new sister. She smells like baby powder, Gerber and poop. Margaret is making gurgling sounds, and we gurgle at each other. Then I say, “here” and give her back to mommy and run out to play.

Easter in April is flush with flowers. White dogwood blooms shower the yellow bus stop near Gilmore Sloan, and pussywillows delight bare branches nearby.Mom clusters red, yellow and pink tulips all over the house as though there are never enough of them. She is soft and happy with spring and Margaret. American Easters are pretty pink, lavender and green Easter clothes, with jackets and bonnets. We go to church and sing “Crown Him with Many Crowns!”

Snow! “It’s like being inside the refrigerator!” We make a snowman, and mom makes us wear jumpsuits. We take the train to grandmother’s house for a real Christmas. "Over the river and through the woods, to grandmother's house we go...." Grandmother’s house has a old house smell you can't ever explain, but it's my favorite smell of America. Our hearts are sweet with the magic of being together in the cold. Mom is especially keen to celebrate Jesus' birth in the winter. She and grandmother are mistresses of high tradition. We play in the snow drifts and then stomp off the snow to deck a piney Christmas tree with olden ornaments. Grandmother builds a log fire that crackles while we sip hot cidery wassail. On Christmas morning, the adults go room to room singing "Merry merry Christmas everywhere, cheerily it rings out in the air, Christmas bells, Christmas trees, Christmas odors on the breeze." We run downstairs in our flannel pjs.Breakfast is fresh baked stollen and scrambled eggs. We open presents one by one. So it doesn't really matter that during Christmas we first get mumps and then measles.

I don't remember when mom tells us we are getting another brother or sister. She gets bigger and bigger. In March, as the ground starts balding and yellow daffodils poke courageously up from the snow, Margaret Juliet arrives. Dad drives grandmother’s Oldsmobile with mom holding a soft white bundle like baby Jesus. We clank pots and pans around the car. “Sssh,” says dad happily, “your new sister’s sleeping.” She curls in a big white bassinette covered with a white veil. Mom brings back flowers in a pretty blue jay vase.

“Can I hold her?”

“Only if you’re sitting on the couch,” mom passes her to me. Johanna and I sniff our new sister. She smells like baby powder, Gerber and poop. Margaret is making gurgling sounds, and we gurgle at each other. Then I say, “here” and give her back to mommy and run out to play.

Easter in April is flush with flowers. White dogwood blooms shower the yellow bus stop near Gilmore Sloan, and pussywillows delight bare branches nearby.Mom clusters red, yellow and pink tulips all over the house as though there are never enough of them. She is soft and happy with spring and Margaret. American Easters are pretty pink, lavender and green Easter clothes, with jackets and bonnets. We go to church and sing “Crown Him with Many Crowns!”

Grandmother takes charge of our Mayflower heritage.

Our elegant grandmother doesn't find out Filipino accents charming. "Say "ellll" at the back of your throat, like this. ELLL. It's not a short 'el'." We're also short on colonial history, so Scott and I take a roadtrip in her Oldsmobile to Colonial Williamsburg and Jamestown Settlement. It's more work for Scott since he's already in third grade. He is in charge of the AAA triptiks and calculates how many miles the car is getting to the gallon. We play perdiddle on American highways.

It's spring and a soft cold rain welcomes us to Williamsburg. After breakfast, we set out in the drizzle down Williamsburg’s cobblestone streets into the bookmaker’s white cottage, smelling of thick red sealing wax and a smoky wood fire. Women and men in colonial costume show us their wares. At the bakery, a hot bread scent wafts through the door of gingerbread and cinnamon. The next day is shining with the softest spring sunlight. We visit a blacksmith, apothecary, and the Governor’s house. This is like stepping into a movie set.

"I want to be American when I grow up!" I glow with colonial fervor as we buy red sealing wax which I plan to affix to all my letters to Phyllis and mail from the colonial post office.

"You are American," says grandmother primly.

We visit the Jamestown settlement, which is not as fun as Williamsburg. It looks more run down, and they have to grow things themselves.

Grandmother lectures on our early family history.

“Jamestown was here before our ancestors came to America. You're descendents of John Alden and Priscilla Mullens who arrived in Plymouth on the Mayflower.”

“What's a Mayflower?”

Shepoints to one ofthe old ships with heavy sails in the harbor, “a boat like that, they took one of those over the ocean. They were pilgrims.”

“Thanksgiving pilgrims?” Scott perks up. We dressed up as pilgrims and indians for Thanksgiving with our Ellinwood friends last year. Scott was assigned a pilgrim, of course.

He's studiously unimpressed with Jamestown, but registers interest in the Powhatan Indian village next to the settlement.

Best of all is the glassworks. In the dark room, man pulls out a glowing molten glob of glass and blows into a long pole – like plastic balloons. Grandmother buys six small green glasses. We drink orange juice from them still.

Mr Montes meets Jesus

When we get back from our fairy tale journey through Williamsburg and Jamestown, something is wrong. Our parents talk in the kitchen when they think we’re asleep, but their mood has troubled the air around us. “What’s wrong?” we ask Scotty because he knows lots more than we do, but he’s not sure either. The next morning, daddy tells us. “Remember Mr. Montes?” “Sure,” we say casually because we don’t really. Dad clears his throat, and then he clears it again. His eyelids are red and brimming. Mom says quietly. “Mr. Montes, daddy’s work friend was in an airplane crash in India a few days ago.” “Is he in heaven, daddy?” Daddy looks so sad. “Yes,” my father says quietly. Mr. Montes is meeting Orange Jesus.

They talk and talk, my parents. Maybe we’re not going back to Manila, they say to each other. We pretend to watch TV so we can listen. “We need a different strategy,” dad is telling mom as though he’s rehearsing for someone else, “a project not relying on one person by with more structure to it.” Mom notices us half-listening. “We’re going home.” That’s all she says.

It's spring and a soft cold rain welcomes us to Williamsburg. After breakfast, we set out in the drizzle down Williamsburg’s cobblestone streets into the bookmaker’s white cottage, smelling of thick red sealing wax and a smoky wood fire. Women and men in colonial costume show us their wares. At the bakery, a hot bread scent wafts through the door of gingerbread and cinnamon. The next day is shining with the softest spring sunlight. We visit a blacksmith, apothecary, and the Governor’s house. This is like stepping into a movie set.

"I want to be American when I grow up!" I glow with colonial fervor as we buy red sealing wax which I plan to affix to all my letters to Phyllis and mail from the colonial post office.

"You are American," says grandmother primly.

We visit the Jamestown settlement, which is not as fun as Williamsburg. It looks more run down, and they have to grow things themselves.

Grandmother lectures on our early family history.

“Jamestown was here before our ancestors came to America. You're descendents of John Alden and Priscilla Mullens who arrived in Plymouth on the Mayflower.”

“What's a Mayflower?”

Shepoints to one ofthe old ships with heavy sails in the harbor, “a boat like that, they took one of those over the ocean. They were pilgrims.”

“Thanksgiving pilgrims?” Scott perks up. We dressed up as pilgrims and indians for Thanksgiving with our Ellinwood friends last year. Scott was assigned a pilgrim, of course.

He's studiously unimpressed with Jamestown, but registers interest in the Powhatan Indian village next to the settlement.

Best of all is the glassworks. In the dark room, man pulls out a glowing molten glob of glass and blows into a long pole – like plastic balloons. Grandmother buys six small green glasses. We drink orange juice from them still.

Mr Montes meets Jesus

When we get back from our fairy tale journey through Williamsburg and Jamestown, something is wrong. Our parents talk in the kitchen when they think we’re asleep, but their mood has troubled the air around us. “What’s wrong?” we ask Scotty because he knows lots more than we do, but he’s not sure either. The next morning, daddy tells us. “Remember Mr. Montes?” “Sure,” we say casually because we don’t really. Dad clears his throat, and then he clears it again. His eyelids are red and brimming. Mom says quietly. “Mr. Montes, daddy’s work friend was in an airplane crash in India a few days ago.” “Is he in heaven, daddy?” Daddy looks so sad. “Yes,” my father says quietly. Mr. Montes is meeting Orange Jesus.

They talk and talk, my parents. Maybe we’re not going back to Manila, they say to each other. We pretend to watch TV so we can listen. “We need a different strategy,” dad is telling mom as though he’s rehearsing for someone else, “a project not relying on one person by with more structure to it.” Mom notices us half-listening. “We’re going home.” That’s all she says.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed