Mom organizing slides as Erika takes shape.

Mom organizing slides as Erika takes shape. This triggers a wave of student protests I've already told you about: the “first Quarter Storm."

Mom, weary and depressed, calls us to the sala.It’s not about the demonstrations, strikes, or fires.

Even dad joins us. This is serious. So we act wenky.

“Could you settle down for a minute, I have something to say.”

Oh, too bigat.

“You’re pregnant” I quip. She shoots me a dark look. My stomach churns. This is my 40-year- old mother.

“How did you know?”

Oh.my.god. Mom is pregnant.

We are already embarrassed by our budding and nubile bodies, with our pheromones in fruitless bloom. With a mother so thoroughly modest, let's call it an annunciation.

“Wow, how many months?” Johanna. Someone had to ask.

“Five.”

In unison, “Five?!”

Scott calculates, “Another Poethig by….May.”

She looks heavy-lidded and withdrawn. Jo and I relapse to silly Manila Girlness.

We can finally adjourn.

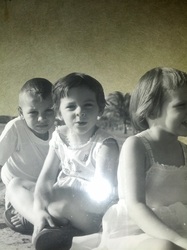

We get silly: "How about Raven Coal Black, or Edgar Allan Poe(thing)?" Mom and dad settle on a long middle name. Sentimental: a Poethig scrap book for posterity in which we feature prominently. Then return to teen solipsism. I embark on my anthropological journey southward right after she arrives.

It's so hot by April that the bomba (Rated X) film, "Erika’s Long Hot Summer" conquers our imagination.

Erika Christy Peter Poethig arrives on May 3rd at St. Luke's Hospital. She's born before dad can get there.

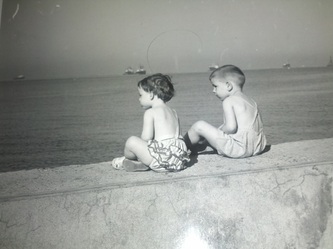

The only Poethig born in the Philippines.

Spunky Erika.

This hot-hot-hot summer, Eleanor Palm, Johanna and I turn to swimming pools. There’s a pool at PhilAm, but it’s crammed with kids. We discover Sulu Hotel, an easy jeepney ride up Quezon Blvd. It's small, often deserted, and the staff are easy going, so we don modest bikinis and swathe ourselves in coconut oil. Johanna’s JASMS barkada joins us – Marilee, Nene, Marilyn, Valerie, wild happy burgis girls. Sometimes we bring Margaret, Margie Palm and their friends to convince our mothers we're generous.

Hot-hot-hot politics are brewing a block from Sulu Hotel. At the "Concon," the Constitutional Convention, three hundred twenty delegates rewrite the Philippine 1935 constitution modeled after the American constitution. The cynics (almost everyone) say this is a Marcos ploy to extend presidential term limits to eight years. A bribing scandal to extend term limits proves it true.

We think this hot convergence presages Erika's political acumen.

Since it's an election year, the campaigns are equally hot and controversial. In August, at Plaza Miranda by the Quiapo Church, someone lobs a grenade onto the platform where Liberal party candidates are speaking. Our very own Protestant Sen Jovito Salonga is swept into the maelstrom. Marcos suspends the privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus. He blames the bombing on the communists, although the Liberal party is the opposition. In popular retaliation, three months later, the Liberals win a majority of the Senate seats, and only two Marcos candidates are elected.

It only promises to get hotter.

In June, at the start of the new school year, I glumly comply with parental demands, sentenced to American purgatory.

"OK, I'll go to International School."

So, no bus-jeepney-through-Quiapo to UP Prep, instead I board the JUSMAG bus with military brats or take a taxi from the Quezon Circle along Hiway 54 through Cubao, over the Guadalupe Bridge into gleaming, suburban Makati to the imperialist, burgis International School.

At least I discover the existentialists. Camus lives with me on the dark side of my moon. I read The Plague, The Myth of Sisyphus, then Kafka's Metamorphosis. But the Camus I love is, Lyrical Essays, drunk on the Mediterranean sun.

To graduate early, I take additional correspondence courses so that by the end of December 1972. The plan is to go to college in the U.S. So, I sign up for all the writing options at IS: the newspaper, Kudyapi, the high school poetry journal for the second year in a row, the yearbook. Mrs. Silverman, a New Yorker who has also introduced me to John Ciardi and Robinson Jeffers, suggests Rutgers, her alma mater.

"It has a good major for Creative Writing."

But Anthropology is my only love and there is no place in the world for Anthropology but the University of Chicago.

I don’t say that back to her.

1970Scott leaves UP for College of Wooster,

Our "Brother Love" becomes a college freshman at University of the Philippines at Dilliman. He takes a bus past Monumento to Quezon Blvd to the acacia-lined campus. He attends Hair as an induction. It may be the Age of Aquarius in America, but in his UP English class, they're comparing Vietnam to Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness. His classes are like sputtering spark plugs - bright, out, hot, dead.

The Diliman tempest arrives in January. Radical students, led by Ericson Boculinao president of the UP Student Council, set up barricades along University Avenue to protest oil prices. When police remove the blockades, someone shoots. It breaks into all-out war returning bullets with pillboxes and Molotov cocktails. We hear that tear gas cleared out the ladies’ dorms.

Scott walks to Basilan Road, shaken. A UP professor, rebuffed at the barricades, had returned with three guns, a helmet and vest and began shooting at the students, killing one. UP students retaliate by burning the professor’s car, bombing the UP guard house, and breaking windows in the Administration Building.

At first UP President Lopez takes a permissive stand. He removes police from the campus on Wednesday to prevent violence, and negotiating with students and faculty. Many of the faculty who live on campus were practically incommunicado since no phones worked, but they and other students are afraid to leave because of looting. In the meantime, pressure groups call for a return to law and order in the university, the resignation of President Lopez and a police take-over.

Gradually, the students take full control of the campus, and set up the “Diliman Commune”. The Diliman Commune set up checkpoints in and out of campus. They prevented all traffic in and out, except for some who wanted to walk. They renamed the buildings, flew red flags from the roofs, manned the radio station, broadcasting revolutionary music and analysis all day. We heard that they commandeered the Chemistry department for molotov cocktails and the Home Economics kitchens for baon for their kasamas at the barricades.

Diliman Commune posts this statement on Feb 13, 1971:

- "WHEREAS, the UP Student Council has expressed solidarity with the Filipino people in their valiant struggle against the American imperialist oil cartel and its local bureaucrat-capitalist allies;

- WHEREAS, the UPSC has endorsed the barricade as a form of protest against such evils;

- WHEREAS, the UPSC vehemently condemns the fascist-puppet State and its campus agents for employing brutally sadistic methods in suppressing legitimate dissent;

- WHEREAS, the UPSC salutes the militant resistance put up by the broad United Front of progressive students, faculty members, non-academic workers, and campus residents who resolutely struggled to defend and liberate the University;

- BE IT RESOLVED AS IT IS HEREBY RESOLVED, that the UPSC commend the revolutionary courage of the heroic defenders of the Diliman Commune against the fascist State and its campus collaborators.

An alumnus of UP Prep, Scott, no radical, is sympathetic. When the mayor of Quezon City and others negotiate with students to remove the barricades, he joins a “fire brigade” line to disentangle the barricade and return the chairs to their classrooms.

The College of Wooster now seemed like his best option. So my oldest brother applies to Wooster in February and is gone by July.

When he turns 18 on July 13, dad takes him to the US Embassy to register for the draft. We hadn't thought about that, so St. Margaret prays for a high number. Mom tells grandmother, “I don’t think Scott has thought about leaving nearly as much as he has thought about getting his two papers in anthropology done.”

He writes papers, continues to deny. Then finally, days before the flight, he packs all his important objects: jeepney signs for Espana Taft Paco, his collection of bus tickets, 12th and 13th century porcelain bowls found at grave sites in Tala caves. Forget the clothes. “Here, take this,” he passes his record player to a surprised Johanna.

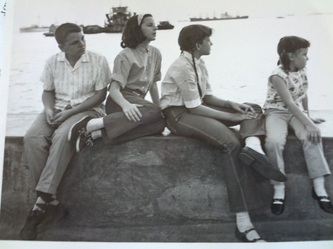

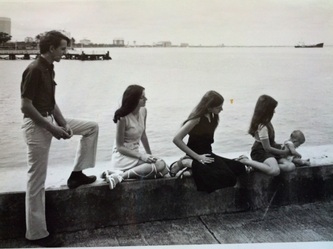

Dad is going with Scott. I wear my new copper-colored peasant blouse hipster pants and macrame belt. We chug happy Erika, pass her around from hip to hip. Scott’s the first to go and gets a real despedida send-off. UP Prep friend Alex, George Padolina, our SS Wright stalwarts. It’s crazy and hot at the airport terminal since the aircon is broken. We gather, mingle and talk about nothing, just to linger.

We hear Philippine Airlines’ last call for Hong Kong and they haven’t gone through immigration!! “Go, go now!” Dad trails Scott down through the closed doors. We think they’r going to come back, but in the confusion, they don’t return. So we dash to the departure deck and wave to the plane as it taxis, takes off, up into the smoggy air. Like that, Scott’s gone. We stand there watching a little longer, then go home.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed