Panatang Makabayan

I am a Filipino patriot.

Each morning at Union Elementary School, we dissolve from piko, jackstones, and habulan statue, to form long crooked lines under the acacia in the courtyard for flag cerémony. The loudspeaker crackles and blasts Bayang magiliw, perlas ng silanganan, as two designated boy scouts jerk our flag up the pole.

We all know the blue means peace over blood. In the white triangle, eight sun rays are the provinces that revolted against Spain and the three stars are Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao. We are the first generation to sing Lupang Hinirang this way. That’s because it was composed in Spanish in 1898, translated to English by the Americans in 1919 and to Pilipino in the 1950s by President Magsaysay who died in the airplane crash. We sing it this way:

Bayang magiliw, perlas ng silanganan.

Alab ng puso, sa dibdib mo'y buhay.

Lupang hinirang, duyan ka ng magiting

Sa manlulupig, di ka pasisiil.

Sa dagat at bundok, sa simoy at

sa langit mong bughaw,

may dilag ang tula at awit

sa paglayang minamahal.

Ang kislap ng watawat mo'y

tagumpay na nagniningning.

Ang bituin at araw niya

kailan pa may di magdidilim.

Lupa ng araw, ng luwalhati't pagsinta,

buhay ay langit sa piling mo.

Aming ligaya na pag may mang-aapi,

ang mamatay ng dahil sa iyo.

A magical nationalism wells up in me, and Gabriela Silang, the one who led her people into battle, reaches down to embrace her small white iha (younger sister) with her brown bayani (hero) arms. Like Jesus, a hero’s greatest joy is to die for you (ang mamatay ng dahil sa iyo). It is a national devotion we sing with the equatorial morning sun already burning a hole in our backs, and me the illegitimate daughter who wants to be forgiven for the sins of my fathers since I’ve been singing Bayang magiliw like a novena for so many years. And anyway, this is a Protestant parochial school, whose students and teachers practice the faith of my fathers after the Americans took the Philippines from Spain. We’re all just a bit illegitimate to the Catholic Filipinos anyway.

Then seven hundred right arms rise, palms forward, and seven hundred voices rumble like the sound of many waters,

Iniibig ko ang Pilipinas.

Ito ang aking lupang sinilangan.

Ito ang tahanan ng aking lahi.

I love the Philippines. This is the land of my birth, this is the home of my ancestors.

As I say it, the words make it so: I love, my birth, my people. This Tagalog is too malalim —deep, as in over one’s head— so I stumble along. We make wonderful promises like Bilang ganti, diringin ko ang payo ng aking mga magulang. (I am a good citizen obeying everybody. I will heed my parents.) The country helps me to be strong, happy, and hardworking. I will serve my country with faithfulness and integrity.

And finish with gusto:

Sisikapin kong maging isang tunay na Pilipino, sa isip, sa salita, at sa gawa.

I will try my best to be a true Filipino in thought, speech and deed.

And so we learn to be isang tunay na Pilipino. We excavate our colonial history and our origin tales, how the first man and woman were born out of the hollow bamboo. Bathala, king of diwatas, the teacher tells us, combines babae and lalake (female and male). One wasn’t made from the other; they loved the earth.

We recall how Tagalogs wrote baybayin, a graceful ancient script. The Aetas and Negritos, our first peoples, arrived on our fair islands over land bridges. We learn how these islands were comprised of sultanates like Maynilad, ruled by Rajah Sulayman, which was conquered by Spaniard Legaspi in 1571. He made it the capital, initiating 400 years of Spanish rule. So we memorize colonial key words for tests: encomendero system, friars, the galleon trade between Manila and Mexico, the Goburza priests who were garroted for defending "natives" (us), and various revolts. We aren't tested on the key words of American rule.

We read about our heros: Apolinario Mabini, Emilio Aguinaldo, Gabriela Silang, Tandang Sora. We nurse a crush for handsome Jose Rizal, executed at Luneta (we think) who wrote our required reading Noli Mi Tangere and El Filibusterismo. But Princess Urduja of Tawalisi is my favorite and I'm awed by Andres Bonifacio's long-haired revolutionaries who founded the secret KKK: Kataastaasan Kagalanggalangan Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan ("Highest and Most Respectable Society of the Sons of the People").

We say we learn this to be tunay na Filipino even though we don’t know what it actually means to be Filipino because we have been colonized so long.

Each morning at Union Elementary School, we dissolve from piko, jackstones, and habulan statue, to form long crooked lines under the acacia in the courtyard for flag cerémony. The loudspeaker crackles and blasts Bayang magiliw, perlas ng silanganan, as two designated boy scouts jerk our flag up the pole.

We all know the blue means peace over blood. In the white triangle, eight sun rays are the provinces that revolted against Spain and the three stars are Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao. We are the first generation to sing Lupang Hinirang this way. That’s because it was composed in Spanish in 1898, translated to English by the Americans in 1919 and to Pilipino in the 1950s by President Magsaysay who died in the airplane crash. We sing it this way:

Bayang magiliw, perlas ng silanganan.

Alab ng puso, sa dibdib mo'y buhay.

Lupang hinirang, duyan ka ng magiting

Sa manlulupig, di ka pasisiil.

Sa dagat at bundok, sa simoy at

sa langit mong bughaw,

may dilag ang tula at awit

sa paglayang minamahal.

Ang kislap ng watawat mo'y

tagumpay na nagniningning.

Ang bituin at araw niya

kailan pa may di magdidilim.

Lupa ng araw, ng luwalhati't pagsinta,

buhay ay langit sa piling mo.

Aming ligaya na pag may mang-aapi,

ang mamatay ng dahil sa iyo.

A magical nationalism wells up in me, and Gabriela Silang, the one who led her people into battle, reaches down to embrace her small white iha (younger sister) with her brown bayani (hero) arms. Like Jesus, a hero’s greatest joy is to die for you (ang mamatay ng dahil sa iyo). It is a national devotion we sing with the equatorial morning sun already burning a hole in our backs, and me the illegitimate daughter who wants to be forgiven for the sins of my fathers since I’ve been singing Bayang magiliw like a novena for so many years. And anyway, this is a Protestant parochial school, whose students and teachers practice the faith of my fathers after the Americans took the Philippines from Spain. We’re all just a bit illegitimate to the Catholic Filipinos anyway.

Then seven hundred right arms rise, palms forward, and seven hundred voices rumble like the sound of many waters,

Iniibig ko ang Pilipinas.

Ito ang aking lupang sinilangan.

Ito ang tahanan ng aking lahi.

I love the Philippines. This is the land of my birth, this is the home of my ancestors.

As I say it, the words make it so: I love, my birth, my people. This Tagalog is too malalim —deep, as in over one’s head— so I stumble along. We make wonderful promises like Bilang ganti, diringin ko ang payo ng aking mga magulang. (I am a good citizen obeying everybody. I will heed my parents.) The country helps me to be strong, happy, and hardworking. I will serve my country with faithfulness and integrity.

And finish with gusto:

Sisikapin kong maging isang tunay na Pilipino, sa isip, sa salita, at sa gawa.

I will try my best to be a true Filipino in thought, speech and deed.

And so we learn to be isang tunay na Pilipino. We excavate our colonial history and our origin tales, how the first man and woman were born out of the hollow bamboo. Bathala, king of diwatas, the teacher tells us, combines babae and lalake (female and male). One wasn’t made from the other; they loved the earth.

We recall how Tagalogs wrote baybayin, a graceful ancient script. The Aetas and Negritos, our first peoples, arrived on our fair islands over land bridges. We learn how these islands were comprised of sultanates like Maynilad, ruled by Rajah Sulayman, which was conquered by Spaniard Legaspi in 1571. He made it the capital, initiating 400 years of Spanish rule. So we memorize colonial key words for tests: encomendero system, friars, the galleon trade between Manila and Mexico, the Goburza priests who were garroted for defending "natives" (us), and various revolts. We aren't tested on the key words of American rule.

We read about our heros: Apolinario Mabini, Emilio Aguinaldo, Gabriela Silang, Tandang Sora. We nurse a crush for handsome Jose Rizal, executed at Luneta (we think) who wrote our required reading Noli Mi Tangere and El Filibusterismo. But Princess Urduja of Tawalisi is my favorite and I'm awed by Andres Bonifacio's long-haired revolutionaries who founded the secret KKK: Kataastaasan Kagalanggalangan Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan ("Highest and Most Respectable Society of the Sons of the People").

We say we learn this to be tunay na Filipino even though we don’t know what it actually means to be Filipino because we have been colonized so long.

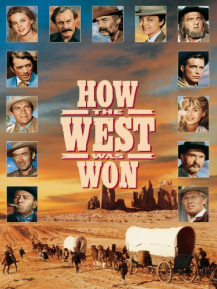

How the West was Won

“How the West was Won” is the rage! The blockbuster movie of the year when I'm in third grade at Union Elementary School. It's three hours long and features flashy new “wrap around” Cinerama. People wait in lines around the block for the chance to see it.

Classmates who had already gone, sing,

"Away away come away with me

where the grass grows wild

and the wind blows free

Away away come away with me

and I'll build you a home in the meadow," to the tune of Greensleeves. They tell us the spoilers like, “…and the buffalo stampede over the mother and her baby.”

Finally mom and dad take us. We watch for two and a half hours before the buffalo trample the mother. Phyllis and I sing with earnest pioneer spirit for “a home in the meadow.” If I forget from time to time that I am the West seeking to settle, my classmates seem to forget that in this story, they are the West to be won.

President Macapagal doesn't forget. In 1962, he moves Independence Day from July 4th (the day designated by the Americans, those sentimental imperialists) to June 12th when in 1898 General Emilio Aguinaldo declared independence for Filipinos in Kawit, Cavite. We return from our U.S. Furlough to find the country celebrating Independence on June 12 in Luneta with General Emilio Aguinaldo as the guest of honor. July 4 is now "Filipino-American Friendship Day."

Classmates who had already gone, sing,

"Away away come away with me

where the grass grows wild

and the wind blows free

Away away come away with me

and I'll build you a home in the meadow," to the tune of Greensleeves. They tell us the spoilers like, “…and the buffalo stampede over the mother and her baby.”

Finally mom and dad take us. We watch for two and a half hours before the buffalo trample the mother. Phyllis and I sing with earnest pioneer spirit for “a home in the meadow.” If I forget from time to time that I am the West seeking to settle, my classmates seem to forget that in this story, they are the West to be won.

President Macapagal doesn't forget. In 1962, he moves Independence Day from July 4th (the day designated by the Americans, those sentimental imperialists) to June 12th when in 1898 General Emilio Aguinaldo declared independence for Filipinos in Kawit, Cavite. We return from our U.S. Furlough to find the country celebrating Independence on June 12 in Luneta with General Emilio Aguinaldo as the guest of honor. July 4 is now "Filipino-American Friendship Day."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed