I have these dreams: I live and breathe under water, a shimmering light green air. Or: our country is occupied. The enemy, hidden, is everywhere. We are the resistance, hide underground, moving and fighting, terrified to be seen. Or: I have learned to fly, a highly technical skill that I learn in a series of dreams. It's a secret.

As far back as I know, I have been white. Passing through the yard, they say, "ay manika!" (doll) and pinch our cheeks. Manika: fragile, pretty, pale, precious. By sixth grade, I am not manika enough. Too much: clumsy, nose too high, a whiteness bright like neon signs in Quiapo, Makati, anywhere.

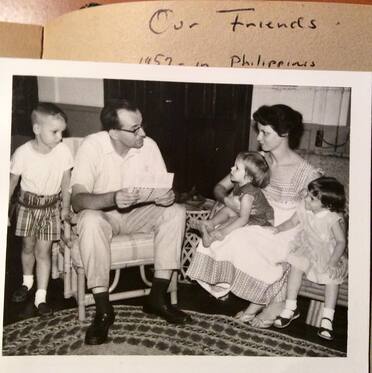

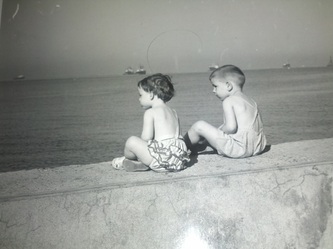

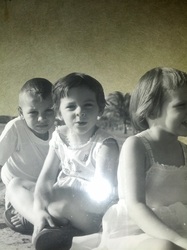

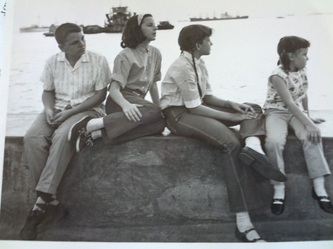

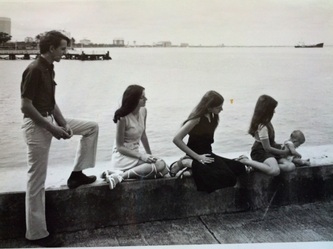

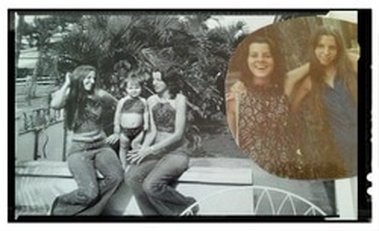

We grew up in the limbo of exile. Home, an American family island in the Philippine Sea. Our world teemed with a mix of aromas: banana-q, garbage, sampaguita, and wind, sun, and music wilder than the American life of grandmother's house. I learned how to be Filipina and that I was not; knew my U.S. passport's privilege but didn't know how to be one. My sisters and I were ex-manikas, "white monkeys," Manila girls in a world pummeled by typhoons, wildcat strikes, student riots, and then, in 1971, curfewed nights.

I live with the name, white monkey, because it's apt enough. A curse for the children of white fright, colonial blight, American might.

Before Victoria and I left on our five-month trip through India, I had another kind of dream: I travel with a woman lover to meet her people in a secret mountain encampment. We stop at a bar enroute. Some women are playing pool. One glances at me, turns to my lover and asks, "Have you told her yet?" "No", she says. The dream shifts, as if unlocked. I am inside and outside of it simultaneously. My lover isn't who I think she is. She is utterly alien. As she morphs into a Kafkaesque creature, I think calmly, "at least I loved her first as human. It will make the transition easier."

There are fish adrift in their aquariums with whom I have more in common than most friends. I live under water again, open my mouth to unshaped sound. No one knows that I am utterly alien, that our world is occupied. No one knows this because I can't speak the language. I can't escape, though I can fly. And no one understands me when I speak. Neither do I.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed