When David Baradas visits again, he's been living in Cubao near his sister. Can he leave his Maranao treasures with us? He's on and off to Mindanao. Mom can't hide her delight. She artfully distributes his cache around our Basilan house sala: brass pots, a sarimanok, a mother of pearl inlaid chest (he got one for us too), a full-scale kulintang, two large brass gongs, exquisite woven fabrics and a three-foot drum. And she mourns them when they leave us.

David Baradas at our screen door, back from Mindanao. From where, he doesn't say. "Something's going on. " He's anxious. It's mysterious. He mentions Manuel Elizalde, who has discovered a “stone age tribe.” Why is he so worried? He sits forward on the couch, he grips his hands. "Something's going on, Dick," he repeats like a novena. Then, "I have to get out of there" as if to warn himself. We -- all of us with different levels of understanding -- are worried too. Elizalde is up to no good.

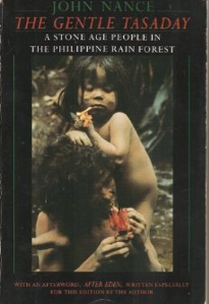

Our anthropologist disappears. In July, news of the "gentle Tasaday" rips through the world. They are tool-using hunter-gatherers, lost in the south Cotobato rain forest, near the T'boli and Manobo, other "lumad," indigenous communities of Mindanao. Are they T'boli? In a matter of weeks, National Geographic, NBC, hundreds of magazines feature the “Lost Tribe of Mindanao." Elizalde founds Panamin for national minorities a cabinet-level position. Panamin is supposed to support research and protection of this stone age tribe.

Eventually, after Martial Law, the hoax is unveiled by a Swiss journalist and the media circus has a second round. The story, retold, is more complicated. Elizalde escapes to Costa Rica with $35 million raised by Panamin. He squanders the money, becomes addicted, and dies impoverished in 1997. Instead of a hero, he's the perpetrator of the greatest anthropological hoax since Piltdown man.

By this time, we are back in the States becoming 'Blue Seal.' I am the first Poethig to return in 1986 - to work in the Bataan refugee camp. I finally track down David Baradas who has moved to Baguio. We are a little awkward, now that I am grown up and have brought my girlfriend. But he still looms larger than life. He consults on museum collections. In his Baguio house, adorned with beautiful cloth and carvings, he serves red rice, mushrooms, fresh vegetables because he doesn't believe in a fridge. We don't talk of the Tasaday.

David Baradas at our screen door, back from Mindanao. From where, he doesn't say. "Something's going on. " He's anxious. It's mysterious. He mentions Manuel Elizalde, who has discovered a “stone age tribe.” Why is he so worried? He sits forward on the couch, he grips his hands. "Something's going on, Dick," he repeats like a novena. Then, "I have to get out of there" as if to warn himself. We -- all of us with different levels of understanding -- are worried too. Elizalde is up to no good.

Our anthropologist disappears. In July, news of the "gentle Tasaday" rips through the world. They are tool-using hunter-gatherers, lost in the south Cotobato rain forest, near the T'boli and Manobo, other "lumad," indigenous communities of Mindanao. Are they T'boli? In a matter of weeks, National Geographic, NBC, hundreds of magazines feature the “Lost Tribe of Mindanao." Elizalde founds Panamin for national minorities a cabinet-level position. Panamin is supposed to support research and protection of this stone age tribe.

Eventually, after Martial Law, the hoax is unveiled by a Swiss journalist and the media circus has a second round. The story, retold, is more complicated. Elizalde escapes to Costa Rica with $35 million raised by Panamin. He squanders the money, becomes addicted, and dies impoverished in 1997. Instead of a hero, he's the perpetrator of the greatest anthropological hoax since Piltdown man.

By this time, we are back in the States becoming 'Blue Seal.' I am the first Poethig to return in 1986 - to work in the Bataan refugee camp. I finally track down David Baradas who has moved to Baguio. We are a little awkward, now that I am grown up and have brought my girlfriend. But he still looms larger than life. He consults on museum collections. In his Baguio house, adorned with beautiful cloth and carvings, he serves red rice, mushrooms, fresh vegetables because he doesn't believe in a fridge. We don't talk of the Tasaday.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed