Manila Bay is six blocks away, but we only go there to visit Luneta Park, where our hero Jose Rizal was shot. He has beautiful black hair that curls on his forehead. "Can you cut my hair like Jose Rizal?" The beautician laughs. American girl.

We sit on the seawall: Scott-Kerry-Johanna, and dad takes a photo. Dad points to garbage on the rocks below and says there is sewage in the water. He calls it urban blight. Urban blight, he’s always talking urban this and that. But little boys still ride the waves.

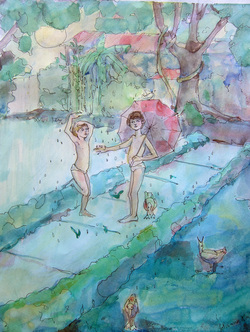

It’s hot season, so back in our yard, we clamber up the slide and shimmy wet shiny bodies into the blue plastic pool at the bottom. Our Filipino barkada don’t join us. American kids at the Interboard Guesthouse do. There’s no plastic pool in their front yard.

One blazingly hot season, Aunti Pampi, the manager 1667-C which is the Interboard Guesthouse, decides on a sandbox in the grassless yard between 1667-B and 1667-C. We have two banana trees and a narra, but the avocado tree rules the dark yard. Ripe avocados plop messily on the ground. It smells of rotten fruit and clay. Only maidenhair ferns flourish in the dimness.

We can hardly stand the excitement. Two workmen measure the space, mix the wet cement and shovel it into the wooden molds. We sit on our backdoor steps as they set the concrete. Auntie Pampi inspects the empty wet square. She’s short a little plump and wears her glasses down her nose.

“Hello Scotty, Kerry, and Johanna.”

“Good apternoon Aunti Pampi,” like angels.

“This is for the Guesthouse children,” Aunti Pampi looks at us over her glasses. Aunti Pampi is friendly, but she’s strict. She is the general of the Interboard Guesthouse where all the missionaries and American guests come and go. I don’t think she likes us too much.

“When is the sand coming?” Scotty can’t wait.

“Next week,” she says vaguely.

“When is the sand coming?” Scotty asks mom three days later.

“I don’t know Scotty.”

“Can you ask Aunti Pampi?”

Mom ignores him after the fifth time.

In the fullness of time, it arrives.

The new sandbox looks like a new baby whale, smooth gray with fine clean glorious beach sand.

“Can I play with my trucks in the sandbox, mom?”

“Ask Aunti Pampi's permission.”

We're careful the first year. When we play with Guesthouse kids, we share our toys. But fine sand is expensive. The second season, we deploy ‘play and run’ guerilla sandbox tactics. Eventually the sandbox is absorbed into the territory of 1667-B.

In the second wet season, Johanna and I requisition the sandbox for Barbie Shipwreck. The sandbox is a tangle of twigs and a black mass of decayed leaves from the narra and avocado trees. Our battered dolls sprawl on the mound dirty sand, sticks and rocks that we’ve piled out of the mucky rain water. We strip them down to survivor wear.

“Barbie, I am hangry,” Johanna is always hungry.

“I will dibe to fish,” My Barbie plunges into the muck, her synthetic hair tangles with the soggy flotsam and pulls up a floating avocado seed.

“Here.”

The sky is a murderous bruise, groaning with rain. Then when it can’t stand it anymore, it lets go in a great relief and rain sprays through the trees, a warm, thick velvet. It splatters on the water in the sandbox, a few twigs fall.

We dangle our barbies around, trying to figure out the next part of our drama.

Johanna looks up at the trees.

“Let’s play shipwreck”

“We are playing shipwreck.”

“No, let’s do shipwreck.” Johanna, wet limp braids, bruised knee, climbs into the wet mucky sandbox with her Barbie in her left hand. She pretends to swim in the pool of dark water that rises around her. The sandbox is cramped for two, we squat there, faces pelted with rain.

We sit on the seawall: Scott-Kerry-Johanna, and dad takes a photo. Dad points to garbage on the rocks below and says there is sewage in the water. He calls it urban blight. Urban blight, he’s always talking urban this and that. But little boys still ride the waves.

It’s hot season, so back in our yard, we clamber up the slide and shimmy wet shiny bodies into the blue plastic pool at the bottom. Our Filipino barkada don’t join us. American kids at the Interboard Guesthouse do. There’s no plastic pool in their front yard.

One blazingly hot season, Aunti Pampi, the manager 1667-C which is the Interboard Guesthouse, decides on a sandbox in the grassless yard between 1667-B and 1667-C. We have two banana trees and a narra, but the avocado tree rules the dark yard. Ripe avocados plop messily on the ground. It smells of rotten fruit and clay. Only maidenhair ferns flourish in the dimness.

We can hardly stand the excitement. Two workmen measure the space, mix the wet cement and shovel it into the wooden molds. We sit on our backdoor steps as they set the concrete. Auntie Pampi inspects the empty wet square. She’s short a little plump and wears her glasses down her nose.

“Hello Scotty, Kerry, and Johanna.”

“Good apternoon Aunti Pampi,” like angels.

“This is for the Guesthouse children,” Aunti Pampi looks at us over her glasses. Aunti Pampi is friendly, but she’s strict. She is the general of the Interboard Guesthouse where all the missionaries and American guests come and go. I don’t think she likes us too much.

“When is the sand coming?” Scotty can’t wait.

“Next week,” she says vaguely.

“When is the sand coming?” Scotty asks mom three days later.

“I don’t know Scotty.”

“Can you ask Aunti Pampi?”

Mom ignores him after the fifth time.

In the fullness of time, it arrives.

The new sandbox looks like a new baby whale, smooth gray with fine clean glorious beach sand.

“Can I play with my trucks in the sandbox, mom?”

“Ask Aunti Pampi's permission.”

We're careful the first year. When we play with Guesthouse kids, we share our toys. But fine sand is expensive. The second season, we deploy ‘play and run’ guerilla sandbox tactics. Eventually the sandbox is absorbed into the territory of 1667-B.

In the second wet season, Johanna and I requisition the sandbox for Barbie Shipwreck. The sandbox is a tangle of twigs and a black mass of decayed leaves from the narra and avocado trees. Our battered dolls sprawl on the mound dirty sand, sticks and rocks that we’ve piled out of the mucky rain water. We strip them down to survivor wear.

“Barbie, I am hangry,” Johanna is always hungry.

“I will dibe to fish,” My Barbie plunges into the muck, her synthetic hair tangles with the soggy flotsam and pulls up a floating avocado seed.

“Here.”

The sky is a murderous bruise, groaning with rain. Then when it can’t stand it anymore, it lets go in a great relief and rain sprays through the trees, a warm, thick velvet. It splatters on the water in the sandbox, a few twigs fall.

We dangle our barbies around, trying to figure out the next part of our drama.

Johanna looks up at the trees.

“Let’s play shipwreck”

“We are playing shipwreck.”

“No, let’s do shipwreck.” Johanna, wet limp braids, bruised knee, climbs into the wet mucky sandbox with her Barbie in her left hand. She pretends to swim in the pool of dark water that rises around her. The sandbox is cramped for two, we squat there, faces pelted with rain.

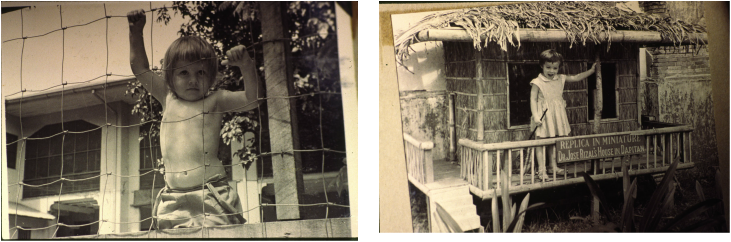

Johanna, "playing in the rain", 1975

Running naked

save for panties

in the rain,

bare feet on wet concrete

suitcase filled with dress up clothes

for typhoon days when howling

wind and streaming rain

kept windows tightly shut,

school uniforms of blue bleed before me

faces blurred by time and hot

frightened tears

once, a white bird

sat outside out window

everyday, a cockatoo

I think, then it flew away

I never saw it again.

Childhood.

KP 1970

save for panties

in the rain,

bare feet on wet concrete

suitcase filled with dress up clothes

for typhoon days when howling

wind and streaming rain

kept windows tightly shut,

school uniforms of blue bleed before me

faces blurred by time and hot

frightened tears

once, a white bird

sat outside out window

everyday, a cockatoo

I think, then it flew away

I never saw it again.

Childhood.

KP 1970

RSS Feed

RSS Feed