We aren’t allowed to lick popsicles in the blue Chevy that was assigned to us by the Interboard Office. It doesn’t really belong to us. “Keep it neat,” mom warns. But we go to Dairy Queen for Dillies, those glorious swirls of vanilla dunked in chocolate. They drip as soon as you lick. I sneak my melting Dilly and lick it over the rear windscreen sill. Bad idea –oops—the Dilly drops off the stick and lands in a big chocolate blob on the sill. “Kerry made a blob!” cries Scott. I burst into tears.

“Don’t cry Kerry,” mom says to me. “Dick, be reasonable.” Every time he gets into the car, dad grumbles at the blobby brown stain. After a while, we forget.

Then the Chevy is stolen when my parents are visiting friends in Quezon City. Dad is in a Monster Bad Mood. But a few days later the black rotary phone rings. Mom picks it up. “It’s for you, Dick” she hands him the phone quizzically. The first part of our story is a detective drama.

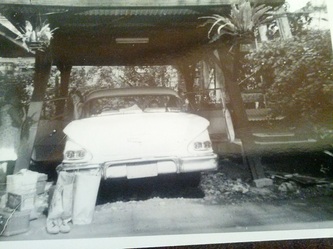

Sunday, dad takes a taxi to Quezon City Detectives Bureau. A few hours later, he drives through the gate in a white Chevy. He gets out and pats the car on the hood, grinning. Our blue car is white! What happened?

“Cokes, my treat, and I’ll tell you.” We swig our special Cokes out of the frosty bottle and wait for the story.

“So... the detective meets me at the office and says that the men who stole the Chevy had it repainted. He asked, was there a distinguishing mark. You know what I said? A chocolate stain!” Dad laughs and looks at me. I beam. Sorrow has turned to dancing.

“Then we took his car to this shady street in San Juan. He leans over to me and says very quiet-like ‘Sir would you walk on the right side of the street? I will walk on the other side.’ And around this corner comes a white Chevy and that detective jumps right into the street! Man, he stops the driver!

It seems at this point like dad is retelling a tale of two cities. “So, he’s standing there with his hands on the hood and he signals to me to check for the chocolate stain. I see the stain, give him the nod, and the detective whips a snub-nosed revolver out of the driver's belt – don’t know how he knew it was there – and orders him out of the car and handcuffs him!” We’re a-gog with admiration.

This is what we learn later on:

The Quezon City policy had located a car theft ring’s “chop shop” in San Juan where stolen vehicles were repainted and motor IDs filed down. There were ready buyers. Clearly, folks in the government’s auto vehicle registration offices turned a blind eye and re-registered the stolen vehicles legally. Our stolen Chevy, now white, had also been given a new set of hub caps. Nice, since the old ones had been stolen.

The car theft web extended to Cavite City were some of the ring lived. Cavite City was also the site of Sangley Point, a U.S. naval base. Other members lived in Pampanga the sugar cane region near Clark Field, the largest U.S. air base in Asia. The police picked up alleged members of the ring in San Juan, Cavite, and Pampanga. The Philippine Interboard Office had decided to pursue the case of car theft, probably on part of the insurance company. Dad was the principle witness.

Now, this story has a part two. Dad’s first visitor is Rev. Fidel Galang.

Dad admires Rev. Galang from Pampanga. “Methodists had a radical history in the Philippines and he was one of them.” Fidel Galang had been chaplain to the Hukbalahap forces resisting the Japanese occupation of the Philippines during WWII. The Huks became bona fide Maoists after the war. Dad says that Rev. Galang slept next to an emissary from Mao’s People’s Army who were fighting Japanese in mainland China.

After some initial small talk the lanky minister asks, “Did you lose something recently, Dick?”

“As a matter of fact, our Chevy was stolen. We got it back. It was remarkable detective action.”

“So, this is the Filipino way Dick. A relative visited me a week ago. I didn’t see him for a long time. He asked if I knew some American missionaries in Manila. Then finally he said one of his inaanak, his godchildren, was involved in the case.

Rev. Galang hesitates, “Well, Dick, I don’t want to become involved, but I promised I would just check the facts.”

My father thinks he can explain the case: “I reported it to the Interboard Office and they told the insurance company, so now we have to see it through.”

Fidel chuckles,“You Americans believe in insurance! Our insurance is pakisama.”

As he takes leave, he smiles, “I think you will receive some other visitors, Dick.”

A few weeks pass before the next visitor arrives. It’s Saturday and my tense mother greets dad as he drives up.

“You’ll never guess who is sitting in the sala.” She doesn’t wait, “the mayor of San Juan. And he has a woman with him.”

My dad greets the couple sitting stiffly on our rattan couch, their untouched glasses of calamansi juice sit in pools of condensation on the coffee table. The mayor is cordial; the mistress seethes. She clasps and unclasps her lacquered fingers.

“Good afternoon, how can I help you?” Dad tries cordial.

Tense pause, she speaks.

“Pastor, your car, you have it now, yes?”

Dad jolts a bit. “Yeeeh. It was stolen, but the police found it. Our Interboard office contacted authorities. They’ve taken the case”

“But sir” she presses, “your car is better di ba? It was given a fresh paint. It has new hubcaps.”

Mother shifts in her chair. The mayor offers a thin smile.

Dad sits forward. “It was painted to change the color, ma’am. It was a theft. The authorities want to bring the criminal case to court.”

The sala is quiet again. The woman’s voice shifts slightly, pleading.

“It’s my brother, Reverend Poethig. He was involved…"

Mom is visibly agitated. Dad says helplessly, without much insight, “I’m sorry for your brother, ma’am. But the case will have to be decided in court.”

What’s wrong with this missionary? The mayor’s mistress leans forward, red fingernails alive on the rattan arm rest, “Your car is better Reverend!”

The mayor does not intercede even as they take their leave. This must have been her idea. It was going to be her car.

Just before the case comes to trial, a pastor from Cavite city comes to my father’s screen door on the first floor of our house. He doesn’t know my father, so they wend politely around the issue for a proper time, talking about his church, politics, family. Finally, the pastor clears his throat.

“Rev. Poethig”

“Please, call me Dick.”

“Well, you know, ….a parishioner passed by my house last week. You know, they did not attend church for a long time and suddenly they came back.” He smiles a little.

“So they asked for me to help. You know, this is our job as pastor. Well, it seems one of their relatives, well, how can I say, this. It seems he is in jail because he was in a chop shop. You know, chop shop?’

Dad nods.

“They told me it was your car that was stolen. They ask me to tell you they are religious people.”

He hesitates, and decides to say what any Filipino would know, ”and would you drop the charges against their relative.”

Now dad knows. He nods again slowly.

After a shared moment of silence, the pastor adds confidentially.

“You see, Rev. Poethig, I am not familiar with this family, so even though I came to talk to you, I am not comfortable doing so.”

Maybe this is the first time my father gets it. Maybe he understood before, but at this remark he makes a quiet calculation: the early bus ride from Cavite, the jeepney here, back to the Cavite bus station, maybe a stop at the market. He wonders at the accumulated tasks of a Cavite pastor in Manila, and how he will make up for the time it has taken to meet this request, and how he will tell the family when he returns there is no good news, and if the family made the request on behalf of another member they did not know. How many networks of request spiral out from the men in the Quezon city jail. My father remembers Fidel’s smile.

We American fraternal workers, we blunder through, we are obstacles in a smooth exchange of utang and return.

Dick leans forward with deeper understanding of Filipino obligation but an American sense of justice. “Pastor, you can blame it on me. But it is out of my hands. The car is not really mine, so I have no authority to drop charges. It belongs to the Philippine Interboard Office and they are allowing the case to forward.” Dad holds out his hands and shrugs slightly, ”It’s out of my hands.”

Maybe when the big American puts out his hands like that, he looks like Pilot when the crowd chooses to release Barnabas, sending Jesus to his crucifixion. But the pastor nods; he understands. It is out of Rev. Poethig’s hands.

“Don’t cry Kerry,” mom says to me. “Dick, be reasonable.” Every time he gets into the car, dad grumbles at the blobby brown stain. After a while, we forget.

Then the Chevy is stolen when my parents are visiting friends in Quezon City. Dad is in a Monster Bad Mood. But a few days later the black rotary phone rings. Mom picks it up. “It’s for you, Dick” she hands him the phone quizzically. The first part of our story is a detective drama.

Sunday, dad takes a taxi to Quezon City Detectives Bureau. A few hours later, he drives through the gate in a white Chevy. He gets out and pats the car on the hood, grinning. Our blue car is white! What happened?

“Cokes, my treat, and I’ll tell you.” We swig our special Cokes out of the frosty bottle and wait for the story.

“So... the detective meets me at the office and says that the men who stole the Chevy had it repainted. He asked, was there a distinguishing mark. You know what I said? A chocolate stain!” Dad laughs and looks at me. I beam. Sorrow has turned to dancing.

“Then we took his car to this shady street in San Juan. He leans over to me and says very quiet-like ‘Sir would you walk on the right side of the street? I will walk on the other side.’ And around this corner comes a white Chevy and that detective jumps right into the street! Man, he stops the driver!

It seems at this point like dad is retelling a tale of two cities. “So, he’s standing there with his hands on the hood and he signals to me to check for the chocolate stain. I see the stain, give him the nod, and the detective whips a snub-nosed revolver out of the driver's belt – don’t know how he knew it was there – and orders him out of the car and handcuffs him!” We’re a-gog with admiration.

This is what we learn later on:

The Quezon City policy had located a car theft ring’s “chop shop” in San Juan where stolen vehicles were repainted and motor IDs filed down. There were ready buyers. Clearly, folks in the government’s auto vehicle registration offices turned a blind eye and re-registered the stolen vehicles legally. Our stolen Chevy, now white, had also been given a new set of hub caps. Nice, since the old ones had been stolen.

The car theft web extended to Cavite City were some of the ring lived. Cavite City was also the site of Sangley Point, a U.S. naval base. Other members lived in Pampanga the sugar cane region near Clark Field, the largest U.S. air base in Asia. The police picked up alleged members of the ring in San Juan, Cavite, and Pampanga. The Philippine Interboard Office had decided to pursue the case of car theft, probably on part of the insurance company. Dad was the principle witness.

Now, this story has a part two. Dad’s first visitor is Rev. Fidel Galang.

Dad admires Rev. Galang from Pampanga. “Methodists had a radical history in the Philippines and he was one of them.” Fidel Galang had been chaplain to the Hukbalahap forces resisting the Japanese occupation of the Philippines during WWII. The Huks became bona fide Maoists after the war. Dad says that Rev. Galang slept next to an emissary from Mao’s People’s Army who were fighting Japanese in mainland China.

After some initial small talk the lanky minister asks, “Did you lose something recently, Dick?”

“As a matter of fact, our Chevy was stolen. We got it back. It was remarkable detective action.”

“So, this is the Filipino way Dick. A relative visited me a week ago. I didn’t see him for a long time. He asked if I knew some American missionaries in Manila. Then finally he said one of his inaanak, his godchildren, was involved in the case.

Rev. Galang hesitates, “Well, Dick, I don’t want to become involved, but I promised I would just check the facts.”

My father thinks he can explain the case: “I reported it to the Interboard Office and they told the insurance company, so now we have to see it through.”

Fidel chuckles,“You Americans believe in insurance! Our insurance is pakisama.”

As he takes leave, he smiles, “I think you will receive some other visitors, Dick.”

A few weeks pass before the next visitor arrives. It’s Saturday and my tense mother greets dad as he drives up.

“You’ll never guess who is sitting in the sala.” She doesn’t wait, “the mayor of San Juan. And he has a woman with him.”

My dad greets the couple sitting stiffly on our rattan couch, their untouched glasses of calamansi juice sit in pools of condensation on the coffee table. The mayor is cordial; the mistress seethes. She clasps and unclasps her lacquered fingers.

“Good afternoon, how can I help you?” Dad tries cordial.

Tense pause, she speaks.

“Pastor, your car, you have it now, yes?”

Dad jolts a bit. “Yeeeh. It was stolen, but the police found it. Our Interboard office contacted authorities. They’ve taken the case”

“But sir” she presses, “your car is better di ba? It was given a fresh paint. It has new hubcaps.”

Mother shifts in her chair. The mayor offers a thin smile.

Dad sits forward. “It was painted to change the color, ma’am. It was a theft. The authorities want to bring the criminal case to court.”

The sala is quiet again. The woman’s voice shifts slightly, pleading.

“It’s my brother, Reverend Poethig. He was involved…"

Mom is visibly agitated. Dad says helplessly, without much insight, “I’m sorry for your brother, ma’am. But the case will have to be decided in court.”

What’s wrong with this missionary? The mayor’s mistress leans forward, red fingernails alive on the rattan arm rest, “Your car is better Reverend!”

The mayor does not intercede even as they take their leave. This must have been her idea. It was going to be her car.

Just before the case comes to trial, a pastor from Cavite city comes to my father’s screen door on the first floor of our house. He doesn’t know my father, so they wend politely around the issue for a proper time, talking about his church, politics, family. Finally, the pastor clears his throat.

“Rev. Poethig”

“Please, call me Dick.”

“Well, you know, ….a parishioner passed by my house last week. You know, they did not attend church for a long time and suddenly they came back.” He smiles a little.

“So they asked for me to help. You know, this is our job as pastor. Well, it seems one of their relatives, well, how can I say, this. It seems he is in jail because he was in a chop shop. You know, chop shop?’

Dad nods.

“They told me it was your car that was stolen. They ask me to tell you they are religious people.”

He hesitates, and decides to say what any Filipino would know, ”and would you drop the charges against their relative.”

Now dad knows. He nods again slowly.

After a shared moment of silence, the pastor adds confidentially.

“You see, Rev. Poethig, I am not familiar with this family, so even though I came to talk to you, I am not comfortable doing so.”

Maybe this is the first time my father gets it. Maybe he understood before, but at this remark he makes a quiet calculation: the early bus ride from Cavite, the jeepney here, back to the Cavite bus station, maybe a stop at the market. He wonders at the accumulated tasks of a Cavite pastor in Manila, and how he will make up for the time it has taken to meet this request, and how he will tell the family when he returns there is no good news, and if the family made the request on behalf of another member they did not know. How many networks of request spiral out from the men in the Quezon city jail. My father remembers Fidel’s smile.

We American fraternal workers, we blunder through, we are obstacles in a smooth exchange of utang and return.

Dick leans forward with deeper understanding of Filipino obligation but an American sense of justice. “Pastor, you can blame it on me. But it is out of my hands. The car is not really mine, so I have no authority to drop charges. It belongs to the Philippine Interboard Office and they are allowing the case to forward.” Dad holds out his hands and shrugs slightly, ”It’s out of my hands.”

Maybe when the big American puts out his hands like that, he looks like Pilot when the crowd chooses to release Barnabas, sending Jesus to his crucifixion. But the pastor nods; he understands. It is out of Rev. Poethig’s hands.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed