Balik (bayan?)

We didn't return to our beloved Malate house, six blocks from Manila Bay. Our Poethig family encamped on Basilan Road in the PhilAm Subdivision. In Quezon City off Hiway 54, it was close to the UCCP offices so dad could walk to work. JASMS had moved nearby. Johanna and Margaret strolled to class. Hiway 54 met Quezon Boulevard at the rotunda. You go left to UP Diliman or turn right to Quiapo. Since Scott and I attended UP Prep, we took the dusty red Philippine Rabbit bus down to Quiapo and a jeepney to Padre Faura back in Malate.

These are our last years in the Philippines. We recombine (Erika Christy Peter Poethig arrives in 1971), then dissolve as a family unit. We smile into despedita cameras, terrified and relieved to finally make the last journey "Stateside." Not balik, not bayan.

In clusters, we disappear into the American fog. Scott's the first. He wants to go. It’s agony here, it’s agony there. But he wants to go. He leaves with dad in July 1971 to attend the College of Wooster. Dad returns and takes Margaret back with him early in 1972, then in the summer Johanna, mom, and Erika sell or pack up everything left in the house. I stay to finish high school and leave in December. It will be years before we gather as a family without distress.

So, let's return to Cosmic 1969:

We arrive in Manila in time for the Moon Walk. Neil Armstrong plants the Stars and Stripes in grainy b&w on our TV. More thrilling for the Philippines, Gloria Diaz is crowned Miss Universe. Tisoy (short for mestizo) comics summed it up, “The US has captured the moon, but the Philippines has captured the Universe!”

And lest we forget, Ferdinand Marcos won a second term as president. Two weeks after this, mom writes her mother about the "Exposé of US subsidy of Philcag troops in Vietnam"

The man on the street favored sending the troops to 'help a neighbor whose house is on fire' but the exposé of Fulbright shames the Philippines in the eyes of the world and attributes base motives to what the average Filipino did in good faith. This hurt is so deep I’m not sure it will really be able to be expressed in words. Instead I predict there will now be a hard coldness where once there was always a warm friendliness even when Filipinos had differences of opinion with the US. There is no fight more vicious in the Philippines than that between brothers. The sad part is that Americans will never know what goodwill and love they have lost because few ever loved the Philippines in the first place. As I have said before, Americans despise the meek.

Love, Eunice

These are our last years in the Philippines. We recombine (Erika Christy Peter Poethig arrives in 1971), then dissolve as a family unit. We smile into despedita cameras, terrified and relieved to finally make the last journey "Stateside." Not balik, not bayan.

In clusters, we disappear into the American fog. Scott's the first. He wants to go. It’s agony here, it’s agony there. But he wants to go. He leaves with dad in July 1971 to attend the College of Wooster. Dad returns and takes Margaret back with him early in 1972, then in the summer Johanna, mom, and Erika sell or pack up everything left in the house. I stay to finish high school and leave in December. It will be years before we gather as a family without distress.

So, let's return to Cosmic 1969:

We arrive in Manila in time for the Moon Walk. Neil Armstrong plants the Stars and Stripes in grainy b&w on our TV. More thrilling for the Philippines, Gloria Diaz is crowned Miss Universe. Tisoy (short for mestizo) comics summed it up, “The US has captured the moon, but the Philippines has captured the Universe!”

And lest we forget, Ferdinand Marcos won a second term as president. Two weeks after this, mom writes her mother about the "Exposé of US subsidy of Philcag troops in Vietnam"

The man on the street favored sending the troops to 'help a neighbor whose house is on fire' but the exposé of Fulbright shames the Philippines in the eyes of the world and attributes base motives to what the average Filipino did in good faith. This hurt is so deep I’m not sure it will really be able to be expressed in words. Instead I predict there will now be a hard coldness where once there was always a warm friendliness even when Filipinos had differences of opinion with the US. There is no fight more vicious in the Philippines than that between brothers. The sad part is that Americans will never know what goodwill and love they have lost because few ever loved the Philippines in the first place. As I have said before, Americans despise the meek.

Love, Eunice

UP Beloved...

“Hoy, Katoy, WAIT!” I yell as the Rabbit bus careens on Highway 54 towards the PhilAm Subdivision gate, a tail of diesel fuel wags behind, ready for the race.

“Hur-ry!”

At 5:30am, my hair is limp from the shower. I kick a loose shoelace and shift the bag of books. For once, Scott and I are going to school together: UP Prepatory High School. Scott's a senior and I’m starting first year. Since I had 8th grade in the States, I’m a year behind my UES classmates who transferred to UP Prep and are now sophomores. It’s awkward.

The bus slows down but doesn't stop so we catch the rail and swing up. Two white kids in uniforms. People look. We find an empty wood plank and settle in. The ticketer shakes her tin canister full of coins. “Quiapo, dalawa.” Scott hands her a peso to make up for me. She blandly whisks out two tickets, rips them and hands them with the change, with quick disapproval at my wet head.

Here's a Flickr link for those Rabbit buses.

“This is TANG-GA - racing Ephren to school,” I grumble. Ephren, Scott's funniest buddy, always gets to school first and Scott is determined to beat him.

Scott ignores me.

I don’t really mind going so early. The thick diesel-fumy congestion of jeepneys, buses, and cars hasn’t yet congealed on Quezon Avenue. In Quiapo, near Plaza Miranda, the bus disgorges us into a river of oncoming jeepneys with signs in their windshields: Taft, Espana, Mabini, then Padre Faura, that’s us. Scott flips his hand, and since we’re so visible (white kids in uniforms), several jeepneys swerve to us. We swing up and bend into the low cavern. I swipe my pleated blue skirt to keep the folds neat. The Padre Faura jeepney cruises over the Quiapo bridge, past the US faux Greek Post Office, the town hall, down Taft, past UN Avenue, swinging right onto Padre Faura. “Ssst, para.” The driver stops as our coins travel up to him hand by hand.

This is my brother's kingdom, University of the Philippines Preparatory High School, the kalaban of UP High in Diliman. We trudge up three flights of drab marble that used to be the Philippine Supreme Court. Our high school is on the decrepit third floor where night classes have left their dunked cigarette butts and coffee cups scattered around the rooms. No matter, I pull out a notebook, find an old chair and write out the homework for Philippine History. I love this place with a proleptic nostalgia.

“Hur-ry!”

At 5:30am, my hair is limp from the shower. I kick a loose shoelace and shift the bag of books. For once, Scott and I are going to school together: UP Prepatory High School. Scott's a senior and I’m starting first year. Since I had 8th grade in the States, I’m a year behind my UES classmates who transferred to UP Prep and are now sophomores. It’s awkward.

The bus slows down but doesn't stop so we catch the rail and swing up. Two white kids in uniforms. People look. We find an empty wood plank and settle in. The ticketer shakes her tin canister full of coins. “Quiapo, dalawa.” Scott hands her a peso to make up for me. She blandly whisks out two tickets, rips them and hands them with the change, with quick disapproval at my wet head.

Here's a Flickr link for those Rabbit buses.

“This is TANG-GA - racing Ephren to school,” I grumble. Ephren, Scott's funniest buddy, always gets to school first and Scott is determined to beat him.

Scott ignores me.

I don’t really mind going so early. The thick diesel-fumy congestion of jeepneys, buses, and cars hasn’t yet congealed on Quezon Avenue. In Quiapo, near Plaza Miranda, the bus disgorges us into a river of oncoming jeepneys with signs in their windshields: Taft, Espana, Mabini, then Padre Faura, that’s us. Scott flips his hand, and since we’re so visible (white kids in uniforms), several jeepneys swerve to us. We swing up and bend into the low cavern. I swipe my pleated blue skirt to keep the folds neat. The Padre Faura jeepney cruises over the Quiapo bridge, past the US faux Greek Post Office, the town hall, down Taft, past UN Avenue, swinging right onto Padre Faura. “Ssst, para.” The driver stops as our coins travel up to him hand by hand.

This is my brother's kingdom, University of the Philippines Preparatory High School, the kalaban of UP High in Diliman. We trudge up three flights of drab marble that used to be the Philippine Supreme Court. Our high school is on the decrepit third floor where night classes have left their dunked cigarette butts and coffee cups scattered around the rooms. No matter, I pull out a notebook, find an old chair and write out the homework for Philippine History. I love this place with a proleptic nostalgia.

Quiapo convergence

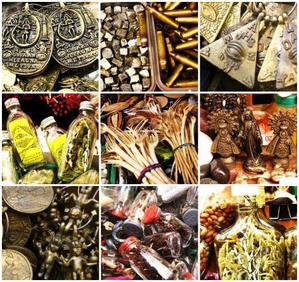

Liberated to travel by jeepney and bus, the city is a great bazaar. When Scott doesn’t accompany me though the smoky diesel-clouded downtown, I move through the traffic like the White Lady. Quiapo church at Plaza Miranda the big transfer point is a favorite sanctuary.

This is the "Minor Basilica of the Black Nazarene" and known for its overwhelming processions.

But I am there for the anting antings cluttering Evangelista street behind the church. Albularyo stalls are piled with mysterious potions in small bottles, mandrake root, tawis, other herbal remedies. Sometimes I squat beside a lola who tells my fortune with her cards on a small table on the back patio of the church. Before you enter the old cathedral, you buy red, black, or white candles in human shapes for different intentions. I choose a white one for purity of thought. Over the church threshold, in the quivering light of votive candles, wizened women shuffle towards the altar on their knees. Others mumble through the stations of the cross.

The Orange Jesus’ famous brother, the Black Nazarene, lies enshrined in glass at the back of the church, as if snoozing between processions. I don’t begrudge him the rest. He looks old and worn with the loving, needful touch of so many followers. You could imagine those two, their backs to me, making tsismis about their churches. Actually, I wasn't conversing much with Orange Jesus per se. Or, let's say, I was conversing with more versions: Mary, acacia trees, the bulol rice gods of the Ifugao.

But when it come to interventions, you take whoever’s available.

My UP Prep barkada go to Ideal (I-dee-al) Theater, the old art deco building on Avenida Rizal, once the Broadway of Manila. At the credits, the screen goes dark. Another brownout.

We cram to the exit. Someone jams their elbow into my back.“

Hoy! Ano ba?" Swept up in the panicking crowd, we edge our way out the Exit, and gasp.

“Susmarijoseph!” The entire block is ablaze! Wild flames lick the blackened sky. Fire engines can’t find enough water to dampen the inferno. It’s pandemonium as the fire leaps buildings.

We have to get out of here!

Someone tells us public transport has detoured due to the fire.

“Sige, Kerry, ayos na, OK?”

“OK lang, ingat, ha.” We separate. I wend through the confusion back to the Quiapo intersection. But when I get to Quiapo, it is crammed with people. Thousands of devotees are gathering for the largest procession of the season – the feast of the Black Nazarene. How did I miss this?

“Nasaan po ang mga bus ng pagpunta sa Diliman?” The man at the edge of the procession turns to me, startled. He didn’t expect a skinny white girl.

“Ay nakareroute nila, hanapin mo yon sa Quezon Bld.” He points vaguely towards Sampaloc. Smoke wafts into Quiapo as the Avenida fire travels deeper into the city. The Black Nazarene procession moves forward undeterred, his image jostling in the thick crowd. Black Nazarene devotees are unfazed by bombscares, demonstrations, or fire. The pandemoniums converge, and I am swept into them.

“Do you nid help?” I glance back to see a young man coming up behind me.I pick up my pace.

“Excuse me, mum, do you nid help?”

He’s running a little behind me. I don’t know why, since he probably is only trying to help the one American girl in Quiapo, but I panic and duck down a crowded street. Oh Jesus, where am I? Disoriented, walking, walking.

Then the ribbon of Quezon Boulevard appears ahead. I arrive across from the rambling campus of University of Santo Tomas about the same time as the UST students across the boulevard. They're pouring out of the campus gate, fists pumping upwards, in call and response,

“Ma-ki-baka!!"

"Hwag ma-takot!”

"Ma-ki-baka!"

"Hwag ma-takot!”

Their gathering is spiky with jubilation and tension.

Our side of Quezon Boulevard is pooling with commuters who have hiked from Quiapo. Jeepneys and busses are crammed so full that men hang by one arm out the doorways. The UST student crowd builds and someone starts shouting into a bullhorn. Wailing sirens indicate the arrival of the police. Our group of commuters is skittish.

Since First Quarter Storm, we know the regimen: Molotov cocktails, police gunfire, general melee, pickpockets. Should I begin walking home at twilight? It will take hours. Nobody knows where I am.

I send out a desperate prayer to the Black Nazarene since His procession is on the prowl. A hand reaches out and pulls me onto the only crowded bus that slows down.

PhilAm subdivision is dark and ghostly after the maelstrom. In a dazed calm, I find everyone at the dinner table. Mom and dad jump up when I arrive. “Where WERE you!” Scott calls out, angry and anxious, “The radio says crazy UST students are throwing rocks and molotovs at the police!”

Police battled the students up and down Quezon Blvd across from UST all night. The fire, procession, and battle caused the worst traffic jam in Manila’s history until that point.

This is the "Minor Basilica of the Black Nazarene" and known for its overwhelming processions.

But I am there for the anting antings cluttering Evangelista street behind the church. Albularyo stalls are piled with mysterious potions in small bottles, mandrake root, tawis, other herbal remedies. Sometimes I squat beside a lola who tells my fortune with her cards on a small table on the back patio of the church. Before you enter the old cathedral, you buy red, black, or white candles in human shapes for different intentions. I choose a white one for purity of thought. Over the church threshold, in the quivering light of votive candles, wizened women shuffle towards the altar on their knees. Others mumble through the stations of the cross.

The Orange Jesus’ famous brother, the Black Nazarene, lies enshrined in glass at the back of the church, as if snoozing between processions. I don’t begrudge him the rest. He looks old and worn with the loving, needful touch of so many followers. You could imagine those two, their backs to me, making tsismis about their churches. Actually, I wasn't conversing much with Orange Jesus per se. Or, let's say, I was conversing with more versions: Mary, acacia trees, the bulol rice gods of the Ifugao.

But when it come to interventions, you take whoever’s available.

My UP Prep barkada go to Ideal (I-dee-al) Theater, the old art deco building on Avenida Rizal, once the Broadway of Manila. At the credits, the screen goes dark. Another brownout.

We cram to the exit. Someone jams their elbow into my back.“

Hoy! Ano ba?" Swept up in the panicking crowd, we edge our way out the Exit, and gasp.

“Susmarijoseph!” The entire block is ablaze! Wild flames lick the blackened sky. Fire engines can’t find enough water to dampen the inferno. It’s pandemonium as the fire leaps buildings.

We have to get out of here!

Someone tells us public transport has detoured due to the fire.

“Sige, Kerry, ayos na, OK?”

“OK lang, ingat, ha.” We separate. I wend through the confusion back to the Quiapo intersection. But when I get to Quiapo, it is crammed with people. Thousands of devotees are gathering for the largest procession of the season – the feast of the Black Nazarene. How did I miss this?

“Nasaan po ang mga bus ng pagpunta sa Diliman?” The man at the edge of the procession turns to me, startled. He didn’t expect a skinny white girl.

“Ay nakareroute nila, hanapin mo yon sa Quezon Bld.” He points vaguely towards Sampaloc. Smoke wafts into Quiapo as the Avenida fire travels deeper into the city. The Black Nazarene procession moves forward undeterred, his image jostling in the thick crowd. Black Nazarene devotees are unfazed by bombscares, demonstrations, or fire. The pandemoniums converge, and I am swept into them.

“Do you nid help?” I glance back to see a young man coming up behind me.I pick up my pace.

“Excuse me, mum, do you nid help?”

He’s running a little behind me. I don’t know why, since he probably is only trying to help the one American girl in Quiapo, but I panic and duck down a crowded street. Oh Jesus, where am I? Disoriented, walking, walking.

Then the ribbon of Quezon Boulevard appears ahead. I arrive across from the rambling campus of University of Santo Tomas about the same time as the UST students across the boulevard. They're pouring out of the campus gate, fists pumping upwards, in call and response,

“Ma-ki-baka!!"

"Hwag ma-takot!”

"Ma-ki-baka!"

"Hwag ma-takot!”

Their gathering is spiky with jubilation and tension.

Our side of Quezon Boulevard is pooling with commuters who have hiked from Quiapo. Jeepneys and busses are crammed so full that men hang by one arm out the doorways. The UST student crowd builds and someone starts shouting into a bullhorn. Wailing sirens indicate the arrival of the police. Our group of commuters is skittish.

Since First Quarter Storm, we know the regimen: Molotov cocktails, police gunfire, general melee, pickpockets. Should I begin walking home at twilight? It will take hours. Nobody knows where I am.

I send out a desperate prayer to the Black Nazarene since His procession is on the prowl. A hand reaches out and pulls me onto the only crowded bus that slows down.

PhilAm subdivision is dark and ghostly after the maelstrom. In a dazed calm, I find everyone at the dinner table. Mom and dad jump up when I arrive. “Where WERE you!” Scott calls out, angry and anxious, “The radio says crazy UST students are throwing rocks and molotovs at the police!”

Police battled the students up and down Quezon Blvd across from UST all night. The fire, procession, and battle caused the worst traffic jam in Manila’s history until that point.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed