Cebu island is the domain of his arch-rival Sergio Osmeña, but his trip there is a great success. The president is eager to return to his bed at Malacañang. Past midnight, his plane lifts off from Cebu’s Lahug airport, skims the sea, and turns north towards Manila over the mountainous spine of the island. The night is clear, calm, even beneficent .

By mid morning on Sunday, March 17 1957, the entire country is filled with anxiety and dread. After a day of fruitless air search, the lone survivor—a journalist badly burned and in shock—is brought by hammock to a hospital in Cebu. Nuya had carried him down the steep slope on his shoulders, then in a hammock to the Balamban River, up and down ravines and slopes for 18 hours. The media praise the heroism of Nuya and his dog Serging. Since the dog was named for the dead president’s rival, its name is changed to Avance!. Both man and dog are honored for their heroism, the man in Cebu and the dog at Malacañang.

My parents learn the news in Tokyo en route to Manila. We arrive the next day at the Manila International Airport. Dick is 31, Eunice is 27, Scott is 3, I’m almost 2, and Johanna is 5 months old. I insist on my sweet blue wool coat, but at the first blast of thick hot air I whip it off.

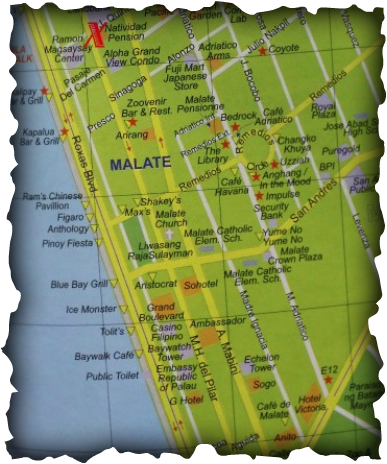

We clear customs and are greeted by fellow fraternal workers: the Palms, Fern Grant, the Crawfords. The men help with luggage as mom holds Johanna in one arm and my hand in the other. “Move quickly!” says Ernie Frei the Swiss missionary with the car, "Vice President Garcia arrives from Australia in a few minutes.” He takes us past the waiting motorcade of state vehicles, and then rice fields. “Scotty, look,” says dad, pointing to a farmer steering his carabao.

As the car turns onto Dewey Boulevard that runs along Manila Bay, a hot salt-fish breeze rustles the palm trees. We pass gathering mourners and vendors at the Shrine of our Mother of Perpetual Help at Baclaran Church. “You’re looking out on the famed Manila Bay where Admiral Dewey defeated the Spanish fleet.” My parents nod. “See that island out there,” he points with one hand as he steers past jeepneys and buses, “see it? Corregidor, last stand of American troops during WWII where the Japanese beat the Americans.” Dick and Eunice peer. “See that white building on the left ahead of us? U.S. Embassy?” He winks, “We only get passes on the 4th of July.” Ernie Frei’s not only Swiss; he’s also American. His Swiss citizenship meant the Japanese couldn’t intern him during the war and he played a critical role as a courier for the resistance.

He swings right down Herran Avenue, and deposits our family at a second floor guest apartment across from an all-night auto shop. The next day, my parents register at City Hall, a large bullet-ridden building with a Quonset hut beside it. On the hottest March on record, Eunice writes in her first letter home:

"We got tied up in the traffic which was mixed up due to the arrival of the cars bringing Magsaysay and the others killed in the plane crash on Sunday. Thousands lined the streets. What a time to arrive here! The next few months are very crucial ones, to say the least. We don’t know what the people’s real feelings are about the loss of Magsaysay."

Two million attended the funeral of President Magsaysay. He was the third president of the new Republic.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed