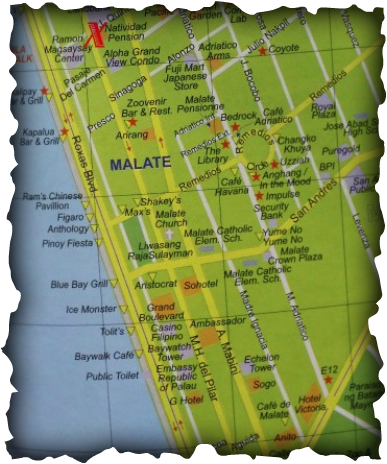

The digital clock blinks 3:23 a.m. in my fan-only room at Pension Natividad. But the fan doesn't work and after the 13 hour flight from SFO, can't sleep, counting number sheep - 3:24 - 3:25 - 3:26. How can jeepneys rumble up Mabini and down del Pilar at this hour? I curl up in my malong, wide awake in the thick pre-dawn.

Then, at the desk in the corner, a soft shift in the airless room. I grab the malong tight, heart lurching, hold my breath, invisible. Soft, like a fade-in, I see a man bent over writing something. When he rises, he's regal. He brushes something off -- is that a waistcoat? I stare hard, heart beating, still trying not to breathe. He absently brushing back his thick hair and turns his head to the door. I gasp, “Mabini?”

"Uh!" he lurches, jostles the papers. Some scatter to the floor. He peers at the bed as he scoops them up. I hoist up the malong, suddenly aware of my open, messy suitcase, my wet underwear on the bathroom rung. He tries a word of Latin, Spanish. Then tight with anger, he lapses into Tagalog, “Ano ang gagawin mo dito sa kwarto ko, American woman?”

His room? “It's Pension Natividad, sir. I paid!” The architect of the Philippine revolution straightens up, pulls down his dark coat and turns his back. In English he hisses. “American saviors! Pft! What I learned about you in Guam. Umalis ka dyan!" He shoos me like a dog. But at this moment, a man in uniform materializes through the door. Mabini half-turns and murmurs in a low voice, “Kumusta General.” Distracted, they speak quietly. Who is that? Finally, I remember. It's Malvar, General Malvar.

The clock turns to 3:33. On cue, they materialize through the walls, the aparador, the mirror, the window. Luis ma Guerrero nods to M.Y. Orosa who greets Madre Ignacia with a sniff on the cheek. Bacobo arrives and takes up a quiet interchange with Nakpil who pulls out his copy of the anthem he composed for Bonifacio. Bacobo jokes, “ Ito nanaman, Nakpil?”

Marcelo del Pilar arrives with characteristic pomp. The first generation of balikbayan celebrities, he founded the nationalist magazine la Solidaridad in Europe. The Filipino multo greet del Pilar with deference and nod imperceptibly at the Spaniard Herran who follows him in. Nobody invited his replacement Pedro Gil, so this at least is a sign that he’s welcome.

“Nandito ba lahat?”

“Dalawa pa,” says Gen Malvar slowly, checking the door.

Padre Faura the Jesuit astronomer and meterologist slips in through the dark window. A thick breeze follows in him. The bayani move to let the Spaniard through. He joins his countryman Herran on the edge of my bed. The padre sits with his hands clasped between his knees his profile tilting longingly towards the window and the city night. Herran's back is tense.

Finally Dr. Vasquez arrives, antiseptic and bustling with friendly busyness. The Malate air in my room sparkles with delight. He is everyone’s favorite. “General, Padre, ah Luis …mi compare Apolinario” (No one else calls Mabini by his full first name, but he smiles back at the doctor affectionately). Dr. Vasquez greets the women, and suddenly stiffens. He sniffs. He looks in my direction, and then sees me, curled against the corner of the bed. The multo stop mid- sentence, turn in unison, and gasp. Their voices rumble “Ah! Aba, aba! ‘susmaryoseph!” "Infiltrator!" I cringe and look pleadingly at Mabini, who does not acknowledge me.

Then a small light brightens the Doctor’s aura.

“Ahhh… iha, iha…” he clears his throat and peers more quizzically.

“Kerry”

“O-o, near Ellinwood. A little girl then… When I was Wright Street…”

The others now gaze with keen interest. A kana who knew Malate streets when they were named American states. The thick air ruffles with ghostly laughter.

General Malvar booms, “Ahay, I lost the revolution but conquered Tennessee!” Everyone titters. “Vermont!” sings Nakpil. "Florida,” Mrs Orosa raises her hand, ”Carolina, Carolina!” the holy Ignacia covers her mouth and giggles like a girl.

“Georgia,” Luis adds his street with dignity. It’s the game, ‘Conquest of the Americas.’

[When did they change the street names in Malate from the American states of occupying troops to bayani of the Philippine- American war. I’m trying to remember all this as the bustle continues.]

“Bacobo?” “Nebraska.”

“Adriatico?” “Dakotas…”

“And who is not here?”

“Leon Ginto…”

“Pennsylvania.” Marcelo del Pilar knows all the street changes but doesn’t want to show off, especially since his street has been del Pilar since the 1950s.

“Sino pa?....”

“Colorado.”

“Sino, sino,”

“Agoncillo!” Marcelo can’t wait.

“Ahhhh,” the ghosts murmur in unison.

“Atchaka” adds the General who won’t be bested, “Admiral Dewey to President Roxas Boulevard!” His voice cracks; it’s a revolutionary memory that still bruises. All heads turn to Manila Bay, two blocks away. A grim, reflective quiet follows the levity.

Mabini watches this, bemused.

“Excuse me, ladies and gentlemen, but we must begin our meeting.” He speaks in English, as a kind of deference, but doesn’t look at me. I sigh and sit up, gather the top of my malong with one hand, feeling about for my chinellas in the dark.

“Permítame acompañarla,” offers Padre Faura quietly as he rises,

“I will teach her to pray a rosary of the constellations.”

Midst the general mumbling, as I push open the door into the humid night, a light cool sense of the Padre at my elbow.

See:

Mock Battle of Manila, 1898

Old Street Names of Manila, Traveler on Foot

Then, at the desk in the corner, a soft shift in the airless room. I grab the malong tight, heart lurching, hold my breath, invisible. Soft, like a fade-in, I see a man bent over writing something. When he rises, he's regal. He brushes something off -- is that a waistcoat? I stare hard, heart beating, still trying not to breathe. He absently brushing back his thick hair and turns his head to the door. I gasp, “Mabini?”

"Uh!" he lurches, jostles the papers. Some scatter to the floor. He peers at the bed as he scoops them up. I hoist up the malong, suddenly aware of my open, messy suitcase, my wet underwear on the bathroom rung. He tries a word of Latin, Spanish. Then tight with anger, he lapses into Tagalog, “Ano ang gagawin mo dito sa kwarto ko, American woman?”

His room? “It's Pension Natividad, sir. I paid!” The architect of the Philippine revolution straightens up, pulls down his dark coat and turns his back. In English he hisses. “American saviors! Pft! What I learned about you in Guam. Umalis ka dyan!" He shoos me like a dog. But at this moment, a man in uniform materializes through the door. Mabini half-turns and murmurs in a low voice, “Kumusta General.” Distracted, they speak quietly. Who is that? Finally, I remember. It's Malvar, General Malvar.

The clock turns to 3:33. On cue, they materialize through the walls, the aparador, the mirror, the window. Luis ma Guerrero nods to M.Y. Orosa who greets Madre Ignacia with a sniff on the cheek. Bacobo arrives and takes up a quiet interchange with Nakpil who pulls out his copy of the anthem he composed for Bonifacio. Bacobo jokes, “ Ito nanaman, Nakpil?”

Marcelo del Pilar arrives with characteristic pomp. The first generation of balikbayan celebrities, he founded the nationalist magazine la Solidaridad in Europe. The Filipino multo greet del Pilar with deference and nod imperceptibly at the Spaniard Herran who follows him in. Nobody invited his replacement Pedro Gil, so this at least is a sign that he’s welcome.

“Nandito ba lahat?”

“Dalawa pa,” says Gen Malvar slowly, checking the door.

Padre Faura the Jesuit astronomer and meterologist slips in through the dark window. A thick breeze follows in him. The bayani move to let the Spaniard through. He joins his countryman Herran on the edge of my bed. The padre sits with his hands clasped between his knees his profile tilting longingly towards the window and the city night. Herran's back is tense.

Finally Dr. Vasquez arrives, antiseptic and bustling with friendly busyness. The Malate air in my room sparkles with delight. He is everyone’s favorite. “General, Padre, ah Luis …mi compare Apolinario” (No one else calls Mabini by his full first name, but he smiles back at the doctor affectionately). Dr. Vasquez greets the women, and suddenly stiffens. He sniffs. He looks in my direction, and then sees me, curled against the corner of the bed. The multo stop mid- sentence, turn in unison, and gasp. Their voices rumble “Ah! Aba, aba! ‘susmaryoseph!” "Infiltrator!" I cringe and look pleadingly at Mabini, who does not acknowledge me.

Then a small light brightens the Doctor’s aura.

“Ahhh… iha, iha…” he clears his throat and peers more quizzically.

“Kerry”

“O-o, near Ellinwood. A little girl then… When I was Wright Street…”

The others now gaze with keen interest. A kana who knew Malate streets when they were named American states. The thick air ruffles with ghostly laughter.

General Malvar booms, “Ahay, I lost the revolution but conquered Tennessee!” Everyone titters. “Vermont!” sings Nakpil. "Florida,” Mrs Orosa raises her hand, ”Carolina, Carolina!” the holy Ignacia covers her mouth and giggles like a girl.

“Georgia,” Luis adds his street with dignity. It’s the game, ‘Conquest of the Americas.’

[When did they change the street names in Malate from the American states of occupying troops to bayani of the Philippine- American war. I’m trying to remember all this as the bustle continues.]

“Bacobo?” “Nebraska.”

“Adriatico?” “Dakotas…”

“And who is not here?”

“Leon Ginto…”

“Pennsylvania.” Marcelo del Pilar knows all the street changes but doesn’t want to show off, especially since his street has been del Pilar since the 1950s.

“Sino pa?....”

“Colorado.”

“Sino, sino,”

“Agoncillo!” Marcelo can’t wait.

“Ahhhh,” the ghosts murmur in unison.

“Atchaka” adds the General who won’t be bested, “Admiral Dewey to President Roxas Boulevard!” His voice cracks; it’s a revolutionary memory that still bruises. All heads turn to Manila Bay, two blocks away. A grim, reflective quiet follows the levity.

Mabini watches this, bemused.

“Excuse me, ladies and gentlemen, but we must begin our meeting.” He speaks in English, as a kind of deference, but doesn’t look at me. I sigh and sit up, gather the top of my malong with one hand, feeling about for my chinellas in the dark.

“Permítame acompañarla,” offers Padre Faura quietly as he rises,

“I will teach her to pray a rosary of the constellations.”

Midst the general mumbling, as I push open the door into the humid night, a light cool sense of the Padre at my elbow.

See:

Mock Battle of Manila, 1898

Old Street Names of Manila, Traveler on Foot

We arrive as the Magsaysay era ends

Handsome President Ramon Magsaysay is a friend of the common tao. He’s a “bare feet in the palace” president, writes an American author. He isn’t tisoy like Quezon, or a Japanese collaborator like Roxas, or corrupt like Quirino. He was a poor boy from Lubao, so he isn’t ashamed to visit the barrios. He invites peasants and laborers to tour Malacañang, the presidential residence, and encourages farmers to telegram him with their complaints. He understands the needs of a rural nation. Throughout the country, people see new bridges, roads, irrigation canals and artisan wells. He starts a land reform plan – mostly it means opening up Mindanao to settlers.

He crushes the Hukbalahap Communists with the help of the American General Lansdale. Some say he won, well, a "Lanslide" in 1953 with America’s assistance. He is America's man in Malacañang.

Cebu island is the domain of his arch-rival Sergio Osmeña, but his trip there is a great success. The president is eager to return to his bed at Malacañang. Past midnight, his plane lifts off from Cebu’s Lahug airport, skims the sea, and turns north towards Manila over the mountainous spine of the island. The night is clear, calm, even beneficent.

But the pilot aims low at the summit of Mount

Manung-gal.

Hrakk! A wing snaps an ibalos tree. With a sickening speed, the plane plunges into the ground, spewing passengers through the gaping metal. Fuselage explodes a glorious orange and the furious heat melts everything left in the plane, including the president. Marcelino Nuya, who lives on the slope, recalls how the raging fire spits like gunshots as he, his son and his dog scramble up the mountain towards the wreckage.

By mid morning on Sunday, March 17 1957, the entire country is filled with anxiety and dread. After a day of fruitless air search, the lone survivor—a journalist badly burned and in shock—is brought by hammock to a hospital in Cebu. Nuya had carried him down the steep slope on his shoulders, then in a hammock to the Balamban River, up and down ravines and slopes for 18 hours. The media praise the heroism of Nuya and his dog Serging. Since the dog was named for the dead president’s rival, its name is changed to Avance!. Both man and dog are honored for their heroism, the man in Cebu and the dog at Malacañang.

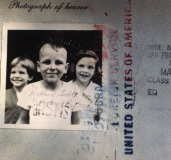

My parents learn the news in Tokyo en route to Manila. We arrive the next day at the Manila International Airport. Dick is 31, Eunice is 27, Scott is 3, I’m almost 2, and Johanna is 5 months old. I insist on my sweet blue wool coat, but at the first blast of thick hot air I whip it off.

We clear customs and are greeted by fellow fraternal workers: the Palms, Fern Grant, the Crawfords. The men help with luggage as mom holds Johanna in one arm and my hand in the other. “Move quickly!” says Ernie Frei the Swiss missionary with the car, "Vice President Garcia arrives from Australia in a few minutes.” He takes us past the waiting motorcade of state vehicles, and then rice fields. “Scotty, look,” says dad, pointing to a farmer steering his carabao.

As the car turns onto Dewey Boulevard that runs along Manila Bay, a hot salt-fish breeze rustles the palm trees. We pass gathering mourners and vendors at the Shrine of our Mother of Perpetual Help at Baclaran Church. “You’re looking out on the famed Manila Bay where Admiral Dewey defeated the Spanish fleet.” My parents nod. “See that island out there,” he points with one hand as he steers past jeepneys and buses, “see it? Corregidor, last stand of American troops during WWII where the Japanese beat the Americans.” Dick and Eunice peer. “See that white building on the left ahead of us? U.S. Embassy?” He winks, “We only get passes on the 4th of July.” Ernie Frei’s not only Swiss; he’s also American. His Swiss citizenship meant the Japanese couldn’t intern him during the war and he played a critical role as a courier for the resistance.

He swings right down Herran Avenue, and deposits our family at a second floor guest apartment across from an all-night auto shop. The next day, my parents register at City Hall, a large bullet-ridden building with a Quonset hut beside it. On the hottest March on record, Eunice writes in her first letter home:

"We got tied up in the traffic which was mixed up due to the arrival of the cars bringing Magsaysay and the others killed in the plane crash on Sunday. Thousands lined the streets. What a time to arrive here! The next few months are very crucial ones, to say the least. We don’t know what the people’s real feelings are about the loss of Magsaysay."

Two million attended the funeral of President Magsaysay. He was the third president of the new Republic.

He crushes the Hukbalahap Communists with the help of the American General Lansdale. Some say he won, well, a "Lanslide" in 1953 with America’s assistance. He is America's man in Malacañang.

Cebu island is the domain of his arch-rival Sergio Osmeña, but his trip there is a great success. The president is eager to return to his bed at Malacañang. Past midnight, his plane lifts off from Cebu’s Lahug airport, skims the sea, and turns north towards Manila over the mountainous spine of the island. The night is clear, calm, even beneficent.

But the pilot aims low at the summit of Mount

Manung-gal.

Hrakk! A wing snaps an ibalos tree. With a sickening speed, the plane plunges into the ground, spewing passengers through the gaping metal. Fuselage explodes a glorious orange and the furious heat melts everything left in the plane, including the president. Marcelino Nuya, who lives on the slope, recalls how the raging fire spits like gunshots as he, his son and his dog scramble up the mountain towards the wreckage.

By mid morning on Sunday, March 17 1957, the entire country is filled with anxiety and dread. After a day of fruitless air search, the lone survivor—a journalist badly burned and in shock—is brought by hammock to a hospital in Cebu. Nuya had carried him down the steep slope on his shoulders, then in a hammock to the Balamban River, up and down ravines and slopes for 18 hours. The media praise the heroism of Nuya and his dog Serging. Since the dog was named for the dead president’s rival, its name is changed to Avance!. Both man and dog are honored for their heroism, the man in Cebu and the dog at Malacañang.

My parents learn the news in Tokyo en route to Manila. We arrive the next day at the Manila International Airport. Dick is 31, Eunice is 27, Scott is 3, I’m almost 2, and Johanna is 5 months old. I insist on my sweet blue wool coat, but at the first blast of thick hot air I whip it off.

We clear customs and are greeted by fellow fraternal workers: the Palms, Fern Grant, the Crawfords. The men help with luggage as mom holds Johanna in one arm and my hand in the other. “Move quickly!” says Ernie Frei the Swiss missionary with the car, "Vice President Garcia arrives from Australia in a few minutes.” He takes us past the waiting motorcade of state vehicles, and then rice fields. “Scotty, look,” says dad, pointing to a farmer steering his carabao.

As the car turns onto Dewey Boulevard that runs along Manila Bay, a hot salt-fish breeze rustles the palm trees. We pass gathering mourners and vendors at the Shrine of our Mother of Perpetual Help at Baclaran Church. “You’re looking out on the famed Manila Bay where Admiral Dewey defeated the Spanish fleet.” My parents nod. “See that island out there,” he points with one hand as he steers past jeepneys and buses, “see it? Corregidor, last stand of American troops during WWII where the Japanese beat the Americans.” Dick and Eunice peer. “See that white building on the left ahead of us? U.S. Embassy?” He winks, “We only get passes on the 4th of July.” Ernie Frei’s not only Swiss; he’s also American. His Swiss citizenship meant the Japanese couldn’t intern him during the war and he played a critical role as a courier for the resistance.

He swings right down Herran Avenue, and deposits our family at a second floor guest apartment across from an all-night auto shop. The next day, my parents register at City Hall, a large bullet-ridden building with a Quonset hut beside it. On the hottest March on record, Eunice writes in her first letter home:

"We got tied up in the traffic which was mixed up due to the arrival of the cars bringing Magsaysay and the others killed in the plane crash on Sunday. Thousands lined the streets. What a time to arrive here! The next few months are very crucial ones, to say the least. We don’t know what the people’s real feelings are about the loss of Magsaysay."

Two million attended the funeral of President Magsaysay. He was the third president of the new Republic.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed