“Hello Dick,”

The resonant voice carries through our Basilan Road screen door.

"David! Good to see you," David Baradas is here! We girls scamper to our rooms to primp and preen. How we love David Baradas. Margaret especially, round-faced, curly-haired Margaret. He poses with baby Margaret at grandmother's pine cabin in Wisconsin, on his lap in Malate, and here on Basilan Road, QC. She curls shyly like a cat.

David Baradas disappears and reaapears without a season. Whenever he shows up, mom's prettier and dad's sharp. Scott's his favorite. We three girls saunter into the sala and try not to stare as he laughs, or watch the soft swoop of this black hair. I imagine a sarimanok perched on his shoulder, insouciantly chewing its claw as he speaks. An incipient adventurer, I'm transfixed by his fieldwork in Mindanao. David Baradas, like grandmother, weave a good tale from any yarn. Their stories awaken a kind of anthropological mysticism, a romance of primordia.

We always call him his full name, DavidBaradas. Never Tito David or Mr. Baradas. He is always older than us but never a grownup. David Baradas and Del Saupalo (Imo) are our favorite kuyas, older brothers, whom we adored. In those Malate years they help dad with the car (in order to drive it, says Imo) and joke, treating us kindly with virile charm. "We were Eagle Scouts," laughs Imo, as if that explains everything.

David Baradas was grandmother's favorite. He is the first recipient of Juliet Blanchard's scholarship for international students at the College of Wooster. He's at Wooster during our first furlough the States so he joins us for Christmas at snowy grandmother's house on Adirondack Trail. We give him our mumps. After Wooster, where he studies the Amish, he heads to University of Chicago for a doctorate in Anthropology. “U of Chicago is the only place for Anthro,” he says. It's true. Think Fred Eggan, Frank Lynch, Robert Fox, and Landa Jocano.

The resonant voice carries through our Basilan Road screen door.

"David! Good to see you," David Baradas is here! We girls scamper to our rooms to primp and preen. How we love David Baradas. Margaret especially, round-faced, curly-haired Margaret. He poses with baby Margaret at grandmother's pine cabin in Wisconsin, on his lap in Malate, and here on Basilan Road, QC. She curls shyly like a cat.

David Baradas disappears and reaapears without a season. Whenever he shows up, mom's prettier and dad's sharp. Scott's his favorite. We three girls saunter into the sala and try not to stare as he laughs, or watch the soft swoop of this black hair. I imagine a sarimanok perched on his shoulder, insouciantly chewing its claw as he speaks. An incipient adventurer, I'm transfixed by his fieldwork in Mindanao. David Baradas, like grandmother, weave a good tale from any yarn. Their stories awaken a kind of anthropological mysticism, a romance of primordia.

We always call him his full name, DavidBaradas. Never Tito David or Mr. Baradas. He is always older than us but never a grownup. David Baradas and Del Saupalo (Imo) are our favorite kuyas, older brothers, whom we adored. In those Malate years they help dad with the car (in order to drive it, says Imo) and joke, treating us kindly with virile charm. "We were Eagle Scouts," laughs Imo, as if that explains everything.

David Baradas was grandmother's favorite. He is the first recipient of Juliet Blanchard's scholarship for international students at the College of Wooster. He's at Wooster during our first furlough the States so he joins us for Christmas at snowy grandmother's house on Adirondack Trail. We give him our mumps. After Wooster, where he studies the Amish, he heads to University of Chicago for a doctorate in Anthropology. “U of Chicago is the only place for Anthro,” he says. It's true. Think Fred Eggan, Frank Lynch, Robert Fox, and Landa Jocano.

Kulintang, the music of God

When I’m 12, the Poethig family visits David Baradas on Simulan island across Lake Lanao where he is conducting fieldwork. He meets us at the Iligan airport to take us to Marawi. We first drop in on the Van Vactors, fraternal workers teaching at Dansalan College in Marawi. David gently pulls my father aside, “Dick, don’t say you’re a pastor. Tell them you’re a teacher.”

What to wear so as not to draw unnecessary attention? I choose my favorite blazing pink kulots and sneakers. We are all in tacky colonial whites - except for Scott.

First we take a pump boat across the cool blue Lake Lanao. Two men curl up in their malongs on the pumpboat floor. Coconut trees and minarets spike the shoreline. The pump boat can't get all the way to beach, so we clamber into the muddy shallows, but the three girls are carried on the shoulders of strong men and let down at the shore. David Baradas guides us to his gracious dark wood slat house. "This is your room,” he gestures to a dark space with one bed and mosquito nets. Johanna, Margaret and I, we look around gingerly, Manila girls in bundokland. “There’s no bathroom,” Johanna murmurs, alarmed. David Baradas points to a white metal chamber pot. She gulps and holds herself valiantly, but later in the dark, I climb out of the mosquito netting to tinkle in the pot.

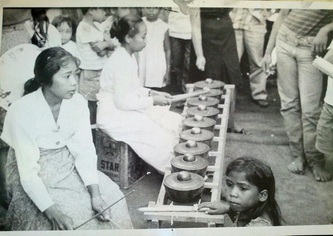

Everyone wants a peek at the Americanos. Towards twilight, the sala is crammed with visitors; latecomers stand on the porch and lean on the open windows. Someone’s six-year-old girl is urged to play the kulintang. A frame of horizontally-placed gongs is set on the floor. She takes her place and deftly pounds out a rhythm with two rubber-coated sticks. I want to remember this magic, here with the gongs in a wood house on Lake Lanao. After a while, the percussive gongs mesmerize the crowd. I think they know and await this moment, the quiet that overtakes you when you are caught up in the syncopated heartbeat of God.

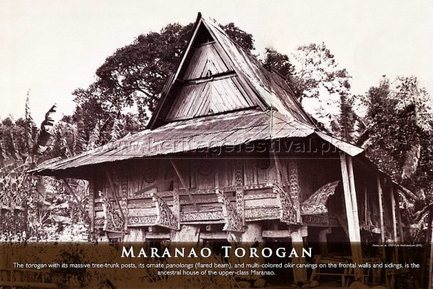

David Baradas is here because this is an old Maranao village and the weathered wooden stilted houses are among the remaining few with elaborately carved eves and winged panolongs (house beams).

What to wear so as not to draw unnecessary attention? I choose my favorite blazing pink kulots and sneakers. We are all in tacky colonial whites - except for Scott.

First we take a pump boat across the cool blue Lake Lanao. Two men curl up in their malongs on the pumpboat floor. Coconut trees and minarets spike the shoreline. The pump boat can't get all the way to beach, so we clamber into the muddy shallows, but the three girls are carried on the shoulders of strong men and let down at the shore. David Baradas guides us to his gracious dark wood slat house. "This is your room,” he gestures to a dark space with one bed and mosquito nets. Johanna, Margaret and I, we look around gingerly, Manila girls in bundokland. “There’s no bathroom,” Johanna murmurs, alarmed. David Baradas points to a white metal chamber pot. She gulps and holds herself valiantly, but later in the dark, I climb out of the mosquito netting to tinkle in the pot.

Everyone wants a peek at the Americanos. Towards twilight, the sala is crammed with visitors; latecomers stand on the porch and lean on the open windows. Someone’s six-year-old girl is urged to play the kulintang. A frame of horizontally-placed gongs is set on the floor. She takes her place and deftly pounds out a rhythm with two rubber-coated sticks. I want to remember this magic, here with the gongs in a wood house on Lake Lanao. After a while, the percussive gongs mesmerize the crowd. I think they know and await this moment, the quiet that overtakes you when you are caught up in the syncopated heartbeat of God.

David Baradas is here because this is an old Maranao village and the weathered wooden stilted houses are among the remaining few with elaborately carved eves and winged panolongs (house beams).

We seek out the mythical Sarimanok, a Maranao symbol of good fortune to anyone who can catch it. Sarimanok means multicolored garment (sari) and chicken (manok). It always holds a fish in its claw and talons. In one story, a sultan of Lanao has a daughter called Sari who is swept away by a multicolored rooster who turns into a handsome prince. For the more devout, Muhammad finds in the rooster in the first of the seven heavens. It is so big, its head reaches the second heaven. David also instructs us to “look for the naga design.” The naga, a dragon or serpent design, shows up on the houses and cloth, woven by women on their backstrap looms in gloomy interiors. I gaze with awe at the last generation of a dying craft. Only their ghosts weave with that tenderness to detail.

Birds, serpents, and trees of life emerge from the abstract patterns. I read later in Tales from Lake Lanao and other Essays about birds of paradise. Hadji Ali Alawi tells Nagasura Madale that the tree is a form of sorta, the leaves are tipak and heaven is called sadiarathul montaha. For every child born, a new leaf grows and written on the leaf is the name of the child and life span on earth. When the leaf falls, it take three to seven days for the life to be finished. Then Malakal Maut, the Angel of Death, will arrive to take the soul. Children perched on the branches are rapas; those who die immediately after birth are called papanok sa aras, birds of heaven/paradise. Hadji Ali Alawi dreams that his own soul becomes a beautiful bird.

He comes and goes, David Baradas, like the sarimanok.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed