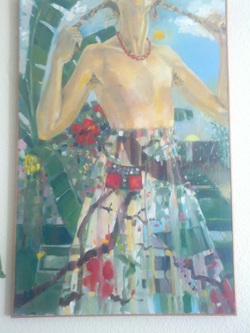

Johanna's self-portrait, 1976. Note Fluffy, lower left.

Johanna's self-portrait, 1976. Note Fluffy, lower left. Mostly, we’re lucky to live beside the Interboard Guesthouse. Out its screen doors come many mk playmates - blond Olson kids from Cebu, the Leininger clan from Legaspi, Palmores and Berans from Dumaguete, Malcolms from Davao, Whites and Deeners from Baguio, VanVactors from Marawi, Mosses from San Pablo, lots of other playmates on their way somewhere. They’re always in good spirits because they are going to the States on furlough or they’re coming back. Like we were last year after settling back at 1667 B Wright Street, our Malate house in the same compound.

Summer vacation is hot season between wets and the Guesthouse is full of temporary playmates. Today, three mk friends from Cebu and Dumaguete have knocked at our screen door to play. We’re tired of tarzan vine, patentero, hide and seek.

”I know!” Johanna gets an idea, but we need a chaperone.

“Scotty, can you go to San Andres Market with us?”

“No.” Then, curious, “Why?”

“To get ducklings!”

Scott, my tawny haired, tense older brother is playing with his friend Arjun the bumbai. They’re at JASMS and will be in fifth grade when school begins in June. Scott grumbles but the bumbai is nice to us and says, “Ok, we will go,” in his funny accent, so Scott can’t say no.

Now we need money.

Johanna shouts from the front lawn, “Mom!” Just to make noise. She leaps up our wafflemarked stairs, pulls out the screen door and heads for The Airconditioned Room. I run ahead of her and get to the door first, turn the cool handle and we step into the cold dry sanctuary with its low rumbling.

“Mom…?” Johanna’s exuberance dissolves at the back of my mother, hunched over her corner desk, her silence refusing our interruption.

“Uh huh?” Mother’s short black hair nods, heavy with reluctance. She doesn’t turn around. Her pen chases the words across the page. Is she grading papers again?

“Never mind,” I tug on Johanna’s shirt. Ducklings another time. But Johanna ignores mother’s “go away” and saunters over to her desk, leaning casually on the corner, just far enough away from our mother so that they aren’t touching. My younger sister peers at the pad’s sharp even script. We are not to mess up the careful stacks of papers. Her Celtic cross is perched on one pile. It’s a mystery of dark silver circles that curlicue other circles. She bought the cross on Iona island, which is somewhere far away and cold, she says. It feels cool when you touch it.

“Can we have 25 centavos each?” Johanna pushes on bravely.

Mom sighs and glances at us sideways, “What for?”

Johanna jumps up, “Ducklings, ducklings!”

“OK, OK, Jo,” I tug at her, “calm down.”

So Scott and Arjun unlatch the Interboard Guesthouse gate that opens onto the thick green tree-lined Dakota. Saint Paul College is in session this morning and parochial school girls’ voices float out classroom windows. Two Paulinians in their black and white checked uniforms wander arm in arm along Dakota Ave. They eye us casually. My brother and the bumbai hesitate and peer down the street.

We know they’re reconsidering.

“Lets go lets go lets go go go,” Johanna catches the arm of the Olson girl and me, and we skip with excitement. We sing, “Sitsiritsit, ali-bang-bang salagintot sala-gu-bang, ang baba-e- aran-tan-tan,” making it up as we go. We swing our hips because it’s about a girl in high heels, but we don’t really know.

Summer vacation is hot season between wets and the Guesthouse is full of temporary playmates. Today, three mk friends from Cebu and Dumaguete have knocked at our screen door to play. We’re tired of tarzan vine, patentero, hide and seek.

”I know!” Johanna gets an idea, but we need a chaperone.

“Scotty, can you go to San Andres Market with us?”

“No.” Then, curious, “Why?”

“To get ducklings!”

Scott, my tawny haired, tense older brother is playing with his friend Arjun the bumbai. They’re at JASMS and will be in fifth grade when school begins in June. Scott grumbles but the bumbai is nice to us and says, “Ok, we will go,” in his funny accent, so Scott can’t say no.

Now we need money.

Johanna shouts from the front lawn, “Mom!” Just to make noise. She leaps up our wafflemarked stairs, pulls out the screen door and heads for The Airconditioned Room. I run ahead of her and get to the door first, turn the cool handle and we step into the cold dry sanctuary with its low rumbling.

“Mom…?” Johanna’s exuberance dissolves at the back of my mother, hunched over her corner desk, her silence refusing our interruption.

“Uh huh?” Mother’s short black hair nods, heavy with reluctance. She doesn’t turn around. Her pen chases the words across the page. Is she grading papers again?

“Never mind,” I tug on Johanna’s shirt. Ducklings another time. But Johanna ignores mother’s “go away” and saunters over to her desk, leaning casually on the corner, just far enough away from our mother so that they aren’t touching. My younger sister peers at the pad’s sharp even script. We are not to mess up the careful stacks of papers. Her Celtic cross is perched on one pile. It’s a mystery of dark silver circles that curlicue other circles. She bought the cross on Iona island, which is somewhere far away and cold, she says. It feels cool when you touch it.

“Can we have 25 centavos each?” Johanna pushes on bravely.

Mom sighs and glances at us sideways, “What for?”

Johanna jumps up, “Ducklings, ducklings!”

“OK, OK, Jo,” I tug at her, “calm down.”

So Scott and Arjun unlatch the Interboard Guesthouse gate that opens onto the thick green tree-lined Dakota. Saint Paul College is in session this morning and parochial school girls’ voices float out classroom windows. Two Paulinians in their black and white checked uniforms wander arm in arm along Dakota Ave. They eye us casually. My brother and the bumbai hesitate and peer down the street.

We know they’re reconsidering.

“Lets go lets go lets go go go,” Johanna catches the arm of the Olson girl and me, and we skip with excitement. We sing, “Sitsiritsit, ali-bang-bang salagintot sala-gu-bang, ang baba-e- aran-tan-tan,” making it up as we go. We swing our hips because it’s about a girl in high heels, but we don’t really know.

We're on our way to San Andres fruit market. Annie returns with meat, fruit, vegetables and rice. Every month, new fruit arrives at our table. In hot April and May, bright yellow mangos, mounds of small red siniguelas, and large prickly skinned jackfruit, langka we call it. By wet August, lanzones, guava, atis and durian. In wetter October, star apples arrive and finally, in dry cool December when red poinsettias announce the arrival of Christmas, the plump pink pomelo. It tastes like sweet grapefruit, says my grandmother.

The San Andres tinderas watch our band of gangly batang amerikano at bumbai arrive and joke good naturedly. Bananas beckon to us from the rafters—red, ladyfinger, senorita, saba – the cooking banana only good for banana-que, banana lumpia and creamy ginataan. These matrons of cornucopia sit behind boxes brimming with rice. Beautiful wooden gantas, three litre scoops, list casually in the ocean of rice. The coconut grating machine whirs, so we gape for a while as the coconut man whacks open a hard brown shell and sets it to the grinder for soft shredded nyog he will put in a brown paper bag for you.

Past piles of tomatoes, green beans, kamote, garlic, gabe, ampalaya, and kangkong, our little gang ambles into the belly of the market. A boy Scott’s age calls, “hey Joe, wanna buy a watsh?” and laughs, “Blue Seal!” It takes a while to get accustomed to the gloom. Scott can’t stop fidgeting, his worried dark eyes searching for the duckling man. He’s feeling responsible for us, which is why he said, "no." It makes him grumpy. We should have asked an adult to accompany us.

The ducklings and chicks are in the same part of the market, in boxes warmed by bright naked bulbs. We peer into the wooden box. It’s a melee of little quacks, fuzzy bodies and webbed feet.

“Excuse me sir, magkano ang mga ducklings?” Scott asks a little too loud.

The duckling man is sitting on a tall wooden stool. He has a round kind face. His white teeth gleam as he chuckles and trains his full attention on the edgy Amerikano.

“Bente cinqo. Ilan ba ang gusto ninyo hijo?”

Hijo? I look from the duckling man to Scott. Hijo means my son, not many grownup Filipinos say that to Scott, and you can see its magic working. My tense older brother softens and looks up into the face of the duckling man for the first time.

“Quatro” he responds more softly, adding “po” for respect. Then he’s a little shy and turns to the duckling box. We know, of course, that the ducklings are twenty-five centavos. We have just enough in our pockets for four ducklings. If we had pockets full of bente cinqos, we would buy the whole box.

Johanna already knows, “Oh, oh, yo-on, yo-on!” as the hand of the duckling man ruffles through the mass of ducklings.

He pulls a wiggling body from the batch and drops it into her cupped hands.

“Eeee!”

The duckling man laughs gently as Johanna examines its tiny yellow head and beady eyes. It’s so little.

It’s Fluffy!” she chirps.

I pick one, Scott chooses another and a Guesthouse kid chooses last bente cinqo duckling. We carry the squirmy ducklings in a paper bag and skip and peek all the way home. Scott laughs too, now that it's mission accomplished.

Scott and Arjun help get hose to fill our beloved sandbox with water. We’re chortling excitedly, “Get the stepping stool!” “Here, let me do it!” We put the stepping stool half in, half out of the sandbox to serve as a diving board.

“Me, me, I want to hold a duckling!” Our feathered charges scuttle delightedly into their swimming hole and spash, ‘quack, quack’. We’re silly with happiness.

“Look at Fluffy, look at Fluffy!” who is doing nothing remarkable.

“So what about Fluffy,” I grumble and nudge my speckled brown duckling to jump off the stepping stool.

‘Quack, quack.’ The ducklings paddle their tiny webbed feet around the little pool.

The ducklings go into a cardboard box which mom sets in the concrete laundry sink overnight so they can’t get out and the rats can’t eat them. The next morning, we relieve the ducklings of their cardboard gulag, which is now splattered and stinky with poop. Our playmates appear from the bosom of Guesthouse. “What’s their names?” “Fluffy,” Johanna holds her prize so tightly it squeaks and wiggles. The three other duckling’s names keep changing. “Pecky, Patty and Plumpy,” I grumble as they patter around their sandbox pool. We play duckling til we’re bored and put them in their box for lunch and siesta. After siesta, our ducklings are funny again. We let them waddle around the grassless yard between our two houses. Then we plop them in their swimming pool again. ‘Quack, quack,’ happy.

Some other Guesthouse kids come over. “Your ducklings?”

Johanna, eyes them, points vaguely, “O-o, Fluffy, Ping, Plumpy, and Pecky.”

An older girl we only know a little grabs Pecky from the water and plops it down on the ground. She begins to walk and it scrambles after her.

“Look, see, Plumpy follows me! She thinks I’m her mother!” “That’s Pecky.”

She’s insistent, “See! Put them in a line, they’ll follow each other.”

It’s true, the ducklings waddle frantically after each other.

Johanna wants to be Fluffy’s mother, so she scoops up her little yellow duck and goes a little farther away.

“Ay naku! So cute!” (This is what people are always saying about us when they pinch our cheeks).

“Let’s go to the flame tree!”

“Plumpy!” “Pecky!” I forget the duckling names, again, “Pampi!” We giggle. “Pampi!”

A Children’s Crusade, we march away from the sandbox to the trunk of the flame tree at the front of the house - child, duck, child duck. Like the Pied Piper’s parade, we march round and round the tree. “ Little Black Sambo!” yells older Guesthouse girl with glee. She laughs, “We gonna to turn to butter!”

We know the story. Johanna walks a little faster. Fluffy scrambles after, blond to butter.

We speed up, Pecky, Pampi, Plumpy waddle, waddle.

Then,

“Fluffy?”

“...Huh?”

“Fluffy! Fluffy! Who squashed Fluffy!”

Pecky, Pampi and Patty halt behind us as we bump into each other and shift our guilty feet.

“SOMEBODY stepped on Fluffy!”

Johanna drops to the grass and tenderly nestles the quivering yellow duckling against her cheek, a pieta of love and suffering. Its tiny beak gapes, open, closed, open.

“Don’t cry, it’s OK, it’s OK” Johanna murmurs.

When Fluffy hangs limp, she rises. She carries the yellow fluff gently, past our weak “sorry” up the front stairs. She won’t come out till dinnertime. She doesn't forgive.

Fluffy is the first of our beloved creatures buried under the acacia tree. Johanna’s only poem appears in the Union Elementary School newspaper:

I had a little duckling

Fluffy was her name

And ever since she died,

My life is not the same.

Forty years later, Fluffy is resurrected as a bright yellow blotch on a concrete box in one of Johanna’s paintings. It hangs in our living room.

The San Andres tinderas watch our band of gangly batang amerikano at bumbai arrive and joke good naturedly. Bananas beckon to us from the rafters—red, ladyfinger, senorita, saba – the cooking banana only good for banana-que, banana lumpia and creamy ginataan. These matrons of cornucopia sit behind boxes brimming with rice. Beautiful wooden gantas, three litre scoops, list casually in the ocean of rice. The coconut grating machine whirs, so we gape for a while as the coconut man whacks open a hard brown shell and sets it to the grinder for soft shredded nyog he will put in a brown paper bag for you.

Past piles of tomatoes, green beans, kamote, garlic, gabe, ampalaya, and kangkong, our little gang ambles into the belly of the market. A boy Scott’s age calls, “hey Joe, wanna buy a watsh?” and laughs, “Blue Seal!” It takes a while to get accustomed to the gloom. Scott can’t stop fidgeting, his worried dark eyes searching for the duckling man. He’s feeling responsible for us, which is why he said, "no." It makes him grumpy. We should have asked an adult to accompany us.

The ducklings and chicks are in the same part of the market, in boxes warmed by bright naked bulbs. We peer into the wooden box. It’s a melee of little quacks, fuzzy bodies and webbed feet.

“Excuse me sir, magkano ang mga ducklings?” Scott asks a little too loud.

The duckling man is sitting on a tall wooden stool. He has a round kind face. His white teeth gleam as he chuckles and trains his full attention on the edgy Amerikano.

“Bente cinqo. Ilan ba ang gusto ninyo hijo?”

Hijo? I look from the duckling man to Scott. Hijo means my son, not many grownup Filipinos say that to Scott, and you can see its magic working. My tense older brother softens and looks up into the face of the duckling man for the first time.

“Quatro” he responds more softly, adding “po” for respect. Then he’s a little shy and turns to the duckling box. We know, of course, that the ducklings are twenty-five centavos. We have just enough in our pockets for four ducklings. If we had pockets full of bente cinqos, we would buy the whole box.

Johanna already knows, “Oh, oh, yo-on, yo-on!” as the hand of the duckling man ruffles through the mass of ducklings.

He pulls a wiggling body from the batch and drops it into her cupped hands.

“Eeee!”

The duckling man laughs gently as Johanna examines its tiny yellow head and beady eyes. It’s so little.

It’s Fluffy!” she chirps.

I pick one, Scott chooses another and a Guesthouse kid chooses last bente cinqo duckling. We carry the squirmy ducklings in a paper bag and skip and peek all the way home. Scott laughs too, now that it's mission accomplished.

Scott and Arjun help get hose to fill our beloved sandbox with water. We’re chortling excitedly, “Get the stepping stool!” “Here, let me do it!” We put the stepping stool half in, half out of the sandbox to serve as a diving board.

“Me, me, I want to hold a duckling!” Our feathered charges scuttle delightedly into their swimming hole and spash, ‘quack, quack’. We’re silly with happiness.

“Look at Fluffy, look at Fluffy!” who is doing nothing remarkable.

“So what about Fluffy,” I grumble and nudge my speckled brown duckling to jump off the stepping stool.

‘Quack, quack.’ The ducklings paddle their tiny webbed feet around the little pool.

The ducklings go into a cardboard box which mom sets in the concrete laundry sink overnight so they can’t get out and the rats can’t eat them. The next morning, we relieve the ducklings of their cardboard gulag, which is now splattered and stinky with poop. Our playmates appear from the bosom of Guesthouse. “What’s their names?” “Fluffy,” Johanna holds her prize so tightly it squeaks and wiggles. The three other duckling’s names keep changing. “Pecky, Patty and Plumpy,” I grumble as they patter around their sandbox pool. We play duckling til we’re bored and put them in their box for lunch and siesta. After siesta, our ducklings are funny again. We let them waddle around the grassless yard between our two houses. Then we plop them in their swimming pool again. ‘Quack, quack,’ happy.

Some other Guesthouse kids come over. “Your ducklings?”

Johanna, eyes them, points vaguely, “O-o, Fluffy, Ping, Plumpy, and Pecky.”

An older girl we only know a little grabs Pecky from the water and plops it down on the ground. She begins to walk and it scrambles after her.

“Look, see, Plumpy follows me! She thinks I’m her mother!” “That’s Pecky.”

She’s insistent, “See! Put them in a line, they’ll follow each other.”

It’s true, the ducklings waddle frantically after each other.

Johanna wants to be Fluffy’s mother, so she scoops up her little yellow duck and goes a little farther away.

“Ay naku! So cute!” (This is what people are always saying about us when they pinch our cheeks).

“Let’s go to the flame tree!”

“Plumpy!” “Pecky!” I forget the duckling names, again, “Pampi!” We giggle. “Pampi!”

A Children’s Crusade, we march away from the sandbox to the trunk of the flame tree at the front of the house - child, duck, child duck. Like the Pied Piper’s parade, we march round and round the tree. “ Little Black Sambo!” yells older Guesthouse girl with glee. She laughs, “We gonna to turn to butter!”

We know the story. Johanna walks a little faster. Fluffy scrambles after, blond to butter.

We speed up, Pecky, Pampi, Plumpy waddle, waddle.

Then,

“Fluffy?”

“...Huh?”

“Fluffy! Fluffy! Who squashed Fluffy!”

Pecky, Pampi and Patty halt behind us as we bump into each other and shift our guilty feet.

“SOMEBODY stepped on Fluffy!”

Johanna drops to the grass and tenderly nestles the quivering yellow duckling against her cheek, a pieta of love and suffering. Its tiny beak gapes, open, closed, open.

“Don’t cry, it’s OK, it’s OK” Johanna murmurs.

When Fluffy hangs limp, she rises. She carries the yellow fluff gently, past our weak “sorry” up the front stairs. She won’t come out till dinnertime. She doesn't forgive.

Fluffy is the first of our beloved creatures buried under the acacia tree. Johanna’s only poem appears in the Union Elementary School newspaper:

I had a little duckling

Fluffy was her name

And ever since she died,

My life is not the same.

Forty years later, Fluffy is resurrected as a bright yellow blotch on a concrete box in one of Johanna’s paintings. It hangs in our living room.

Pets

"Out of the eater, something to eat; out of the strong, something sweet.”

Judges 13:13

We had generations of ducklings. Only two survived from a miserable stinky diarrhea that usually took them away from us. Ping and Squeaky were wiry and irritable. I loved them, inadequate mother her gone-wrong kids. I dug up worms in the dark earth near the acacia and hand fed them several times a week. The sandbox was too small and by hot season, Squeaky patrolled the front yard. She lowered her crooked neck when anyone approached the house, squawking as she ran, her wings flapping. Ping copied. They never attacked the family, but visitors had to run to the concrete steps to avoid a peck to the shin.

The parents weren’t amused.

“But who else has guard ducks? They’re fierce!” Not the best defense.

“I think the ducks would be happier out to UP. There’s a pond.” Mom.

“Someone will eat them!”

“You kidding? They’re tough as nails.” Dad. So we gave Squeaky and Ping to the Palms who, we were told, released them by the pond.

The front yard was quiet for a while.

You get used to pets as fevered, food or feral in Manila. It’s Samson’s riddle, "Out of the eater, something to eat; out of the strong, something sweet.” Of course, he’s talking about a beehive in a dead lion’s jaw, but proof texting has its merits. We offered leftovers to the outside cat, Melting Snow as she bore litter upon litter in the crawl space under the Ellinwood Bible School dorm. When she disappeared, leftovers went to our neighbor’s baboy, whose death squeals ruined my interest in lechon at fiesta season. I have already confessed to ant wars and dragonfly leashes. We tried turtles (died early) rescued fledglings to prolong their agony dribbling condensed milk down their beaks. My guinea pig mothers ate their babies. “Maybe the cage is too small,” dad worried. So we make a small cage with wooden sides and chicken wire top. I set on the lawn during the day so they crop the grass into rectangular patches. But they were just too plump and sweet. I lurch awake one night, not sure why. In the morning, their cage is empty. No doubt they went the way of our cocker spaniel puppy, who lived with us a week. I resolved that it didn’t matter if our pets were eaten since nothing lives forever, and as long as they weren’t afraid when they died it was always best to be useful.

"Out of the eater, something to eat; out of the strong, something sweet.”

Judges 13:13

We had generations of ducklings. Only two survived from a miserable stinky diarrhea that usually took them away from us. Ping and Squeaky were wiry and irritable. I loved them, inadequate mother her gone-wrong kids. I dug up worms in the dark earth near the acacia and hand fed them several times a week. The sandbox was too small and by hot season, Squeaky patrolled the front yard. She lowered her crooked neck when anyone approached the house, squawking as she ran, her wings flapping. Ping copied. They never attacked the family, but visitors had to run to the concrete steps to avoid a peck to the shin.

The parents weren’t amused.

“But who else has guard ducks? They’re fierce!” Not the best defense.

“I think the ducks would be happier out to UP. There’s a pond.” Mom.

“Someone will eat them!”

“You kidding? They’re tough as nails.” Dad. So we gave Squeaky and Ping to the Palms who, we were told, released them by the pond.

The front yard was quiet for a while.

You get used to pets as fevered, food or feral in Manila. It’s Samson’s riddle, "Out of the eater, something to eat; out of the strong, something sweet.” Of course, he’s talking about a beehive in a dead lion’s jaw, but proof texting has its merits. We offered leftovers to the outside cat, Melting Snow as she bore litter upon litter in the crawl space under the Ellinwood Bible School dorm. When she disappeared, leftovers went to our neighbor’s baboy, whose death squeals ruined my interest in lechon at fiesta season. I have already confessed to ant wars and dragonfly leashes. We tried turtles (died early) rescued fledglings to prolong their agony dribbling condensed milk down their beaks. My guinea pig mothers ate their babies. “Maybe the cage is too small,” dad worried. So we make a small cage with wooden sides and chicken wire top. I set on the lawn during the day so they crop the grass into rectangular patches. But they were just too plump and sweet. I lurch awake one night, not sure why. In the morning, their cage is empty. No doubt they went the way of our cocker spaniel puppy, who lived with us a week. I resolved that it didn’t matter if our pets were eaten since nothing lives forever, and as long as they weren’t afraid when they died it was always best to be useful.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed