Kerry likes the provinces” remarks mom dryly. Dad’s eyes widen as she hands me 400 pesos in birthday money for flights to the Visayas and Mindanao for my birthday.

I set out like the fabled Muslim explorer Ibn Battuta and return with pasalubongs for everyone. Here begins a compilation of various travels.

I set out like the fabled Muslim explorer Ibn Battuta and return with pasalubongs for everyone. Here begins a compilation of various travels.

Siquijor, Negros Occidental

"Siquijor? The sorcerer’s island? Ingat!” We hear this often at Silliman University, the UCCP-related college in Dumaguete. You can see small Siquijor island from the Dumaguete seawall. A friend from Silliman takes red-haired Nancy and me across on a banca, a canoe with a bamboo outrigger. The sea breeze is stiffens our hair, and the spray salts our clothes. From the banca, the coconut-tree-lined island looks welcoming enough. Now, with so many web encounters of mangkukulam, the worry is only for show.

We arrive at Siquijor's port stiff but happy. Visayas' sun glazes the azure sea, blue and clear as breath. Breathless, I put my hand through the air to meet transparent water. Below, a parrot fish glides above orange coral and a neon blue starfish. I think of Narnia tales and Reepicheep, the little mouse on the Voyage of the Dawn Treader in search of the end of the world where the water is sweet. Is it sweet, this sea? Naked boys jump off a ferry for centavos, laughing. I throw a cinco and laugh too.

We three wedge into a pedicab and buzz along the coconut-fronded avenue in search of a mangkukulam. I hear they take a doll part, a sliver of fingernail, lock of your hair and whisper a spell to make you sick. But I want to see, to learn what they do. What would it take to be one?

First we make a courtesy call to the mayor who invites us into his dark concrete house for a Coke. He laughs when he learns why we’ve come. Silly American girls playing with fire. Yes, he knows a mangkukulam. He motions the pedicab driver over to give him directions. He also knows. It’s a small place. We stop at a nipa hut on stilts.

A young man in a red tee shirt looks out and comes down his ladder.

"Magsalita na kayo ng Tagalog?" I ask, a little shy.

"Konte lang," the young man says shyly. "Cebuano."

His wife ignores us. She curls quietly on the hard wooden bench nursing their new son. We climb up the ladder to his one room where a single calendar of President Marcos and Imelda adorn the walls.

“Pahinga ditto,” he points to a wooden bed. We’re both a little nervous. I go over and lie on my back. He takes a straw and blows bubbles in a water glass that muddies as it travels above my body.

"To cleanse your spirit daw," my friend translates.

“Ay salamat.” I nod, hoping he’ll believe that I believe him.

“May love potion ba kayo?” Love potion! This he knows about. He leaps up on his wife’s bench to russle about in the eves, extracting a small chunk of charcoal. Handling it carefully with both hands, his eyes sparkle as he offers it to me. My friend gives instructions: Say your name over this seven times, and put it in the personal belongings of the one you want to love you. He wraps it in a little piece of paper with markings I don't understand.

It’s clearly time to go. We thank and thank and leave some pesos as a gift, “para sa anak mo” (for your child).

"Tapos na ba?" asks the pedicab driver.

He will embellish the tale for buddies at the palenke by the port. The sea spray sops us again on our banca back to Dumaguete. I never try the love potion.

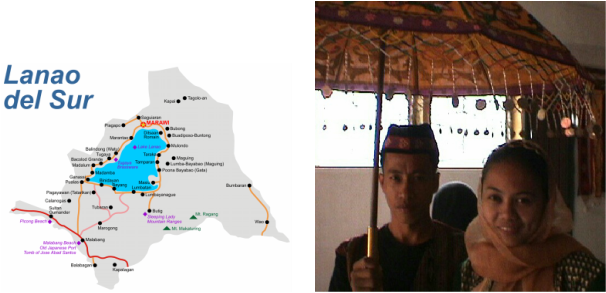

Marawi, Lanao del Sur

We first visited Marawi bordering Lake Lanao first with David Baradas. The Islamic City of Marawi is Maranao territory, full of exquisite artistry from their weaving to silver inlay to architecture. This is far, far from Manila and a the most exotic place I visit. When I'm fifteen, I return to visit Barbara Cort, a Frontier Intern whose father John Cort administered the Philippine Peace Corps program for several years. Barbara teaches at Dansalan College with a beautiful view of the lake. It is no competition for the Mindanao State University's expansive campus.

Barbara plaits her hair like abaca and winds the rope around her wide, tan face. She calls to the woman above in the dark house, ‘hoy Jasmin,” and the unseen woman appears at the dark wooden window. Jasmin clucks and her laughter scatters the birds in the eves. Two Muslim boys saunter by, one pulling the knob of his malong tight at his waist, They gape.

“It is because,” states Barbara, “if a boy would stare at his own women that way, she could force him to marry her.” “Then we are being molested?” I ask

"Well, maybe more like tested,” she says and laughs again. The birds return to the eves.

It takes the car an hour and a half to drive from Marawi to Iligan. I miss the flight back to Dumaguete. On the way there, the driver tells me, I think to justify our delay, that two planes crashed that week, one at the Iligan-Marawi airport. Another flight is ready to taxi as I drag my bags to the counter and a kind steward rushes me onto it just in time.

“She’s that age,” writes mom to grandmother about the steward's special care.

“Fortunately for concerned mothers, it’s hard to disappear in the Philippines, and although I had heard nothing from her, I found out she had gotten to Marawi all right and back to Dumaguete safely from people who had seen her. I met them on the steps of Ellinwood. How’s that for personal reportage?”

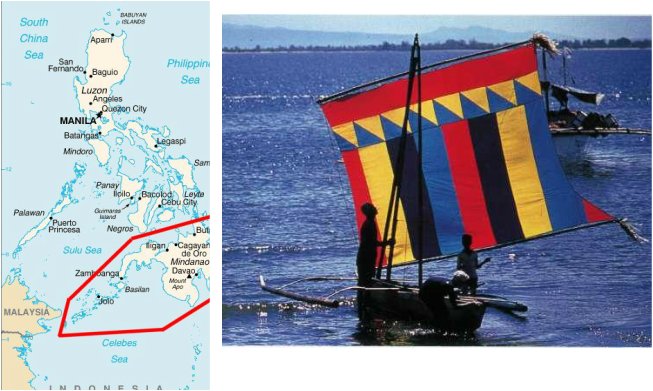

Zamboanga, city of flowers

Zamboanga of 1970 and Zamboanga of mid-2000 are different cities. Red-haired Nancy and I stay with the dad's friend Cipriano Malonzo when we visit Zamboanga in the summer of 1971, but it's the Zamboanga visit of my 15-year-old self that I cherish. In those years, Zamboanga is a bustling, lush, edgy but hospitable smuggler town. Zamboanga city was colonized by the Spaniards as an long-standing outpost against Muslim pirates. This is why Chavacano is a kind of creole Spanish. Zamboanga carries an aura of the borderlands - edge of the nation, the edge empire, post-colonial Spain, American unease with Islam. The city is gracious with wide lanes, bougainvilleas and old acacias along the sea wall. In the 1970's the Badjao, sea gypsies, still use unfurl their colorful sails, and Yakan weavers of Basilan sell psychedelic woven cloth. In the 1970's, I am too much a hybrid "imperial Manila" girl to detect trouble brewing. This is before we know much about "Jabidah," the massacre of Muslim trainees by the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) in 1968, or understand the effects of Visayan settlers in Mindanao, or understand the anger and demands of the Moro National Liberation Front. This is before Mindanao is synonymous with "conflict zone." When I arrive in the 1980's under Martial Law, the city has the feel of a free-fire zone. A year later during the Marcos-Cory campaign season, one feels a sliver of hope. When I return in the mid-2000's, it is still lovely but seems both spiky and worn down from the conflict. Now the only Americans who visit seem to be military sent by the Visiting Forces Agreement.

My first trip Zamboanga in 1970 is an encounter with leprosy. Since Aunti Soli is head of the American Leprosy Mission, she takes Luna and me to the leprosarium there. "We call it Hansen's disease now," she says, but everyone knows it as leprosy. We've also visited the Tala Leprosarium in Caloocan city, 30 miles from Manila. We are collecting family data for the Christian Children’s Fund to identify children for sponsorship. Since the leprosy colony is split between Muslims and Christians, we need to find an equal number of eligible children in both communities. The sherbert-yellow administration building of the leprosarium is circled by a carabao grass lawn shaded by high acacias pink with bloom. A wide-horned carabao grazes in the far corner of the lawn. To the right of the administration building, a pre-school adds happy chatter to the air.

Leprosy is a zombie terror; it is slow terrible horror. Since you lose nerve endings, you don't feel pain when rats gnaw off fingers in the night. Eventually, your face eats itself; your ears and nose rot. Your body collapses in on itself like an old soggy house. That night before I tuck the mosquito net into my mattress, I get down on my knees

"Please, so that I don't cringe," I pray. In the morning, Luna and I set out in different directions. It's hot, hot, hot, of course, and wearying. But the days humble us. We are comfortable Manila teenagers greeting families of healthy and leprosy-stricken members who have been ostracized to this place. We ask simple questions about their family size and children’s ages, but even this simple meeting is excruciating. The youngest hugs his mother’s knees. I touch withered hands, trying to look casually at the sunken withered faces of people who do not look at me. We stop at the gate of a ramshackle nipa hut and a child comes out. No, she won't come, she says. For years, I see the faces of the children playing in front of their houses. They look up, freeze in a blank look. Run away. What is it like for a healthy child to be imprisoned as a pariah?

After this, we visit Basilan Island. Aunti Soli's brother manages the Menzi plantation on Basilan Island, so we visit the rolling hills of rubber. Rubber, as far as the eye can see. But Basilan's future is due for upheaval. In 1988 after the Marcos dictatorship, the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP) splits up foreign-owned plantations and replaces them with plantation cooperatives. Then, Basilan joins the Autonmous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) and the Muslim Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and Abu Sayyaf set up base camps and hold hostages there.

Back in Zamboanga, we walk along to the old Spanish fort, then barter in the Muslim market for old brass and smuggled batik from Malaysia. Luna turns over some batik, which has doubled in price now that they see me. “Anong akala mo sa akin, Americano?” I toss my head in a suplada-mestiza way. As usual, it’s effective. The tinderas laugh good-naturedly, start up a Tagalog interchange and the price comes partway down.

The next day Aunti Soli takes us to the Muslim burial island, hot white sand and old carved boats marking the dead. “Sometimes there are bones on the beach,” says Aunti Soli. Luna and I don’t know whether she’s teasing. We walk there respectfully, but it's so blazingly hot that all the color is leached from the air. I long for a cold calamansi juice.

In Manila, I can't forget, reflect on what the body is and "how hulls are cast from fruit." But we also wear our newly aquired batik outfits to the Cultural Center.

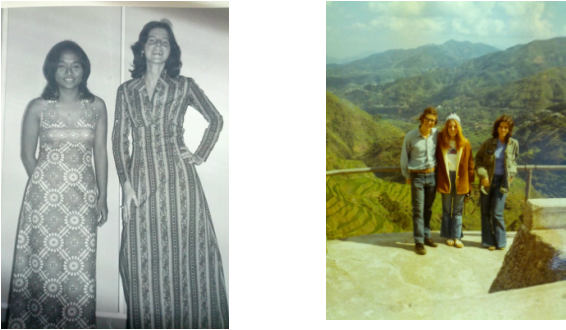

Turn 16 in Bontoc

In April 1971, red-haired Nancy, a friend from International School, her boyfriend, and I visit the Cordillera mountains. I have never been north of Baguio, our family Christmas destination. Banaue, Ifugao Province is world famous for the rice terraces. We'll go there first, then though Mountain Province to Bontoc and finally the artist colony of Sagada. We'll loop through Baguio, Benguet Province before arriving in Manila.

In the mid-1980s I retrace my virgin mystery tour with Jenise, my sporty girlfriend. We enter in through the same portal to vertical worlds wary of lowlanders. The mountain people are muscular and easy to exoticize: Kalinga, Igorot, Ifugao, which means mountain people Their god Matungulan supervises the sacred process of rice planting. For a Manila Girl this mountain life is a bit too stressful. It's a lot of nature and walking up and down.

On Banaue's paddies distant figures transplant rice; our bus climbs higher and deeper into clammy fog. Nancy, her boyfriend and I reach Banaue a scappy town late afternoon. In the chilly mountain twilight, the sky is suggared with stars. Our breakfast of soggy pancakes with fresh strawberries is the most delicious I ever tasted. I am 15 and on an adventure.

"How about Batad," suggests Nancy the next day. Batad is a lovely amphitheater of a town where Marshall Scott lives, I think. The Poethigs don't hike. After a muddy climb in sandals your heart hurts! At the top, Ifugao women with rattan backpacks chuckle at me and generously offer some aid: swing your hips, back straight. It's a lesson I never forget.

We board a Bontoc-bound jeepney. At one point, the jeepney driver maneuvers over thin plank covering a wash-out crevasse. Rice terraces are replaced by a surprisingly lush foggy mountain jungle .Mountain slopes are mostly mournfully denuded. But in river valley, small gardens carved into the slope are planted with spirals of vegetables: cauliflower, green beans, carrots. The cauliflower curlicues are like an earth tattoo.

Bontoc is a market town nestled in a high valley along the rocky Chico river. Why am I so enamored with Bontoc? Is it the Cordillera moutons close around us? Is it the chortling Chico river? In a few years Marcos will provoke armed struggle throughout the Cordilleras. The Kalinga will resist his plan for a Chico River mega-dam. Kalinga women will stand against troops and Macli-ing Dulag will refuse the envelope of Manuel Elizalde of PANAMIN, a nonprofit for cultural minorities. Macli-ing Dulag will say, “This envelope can contain only one of two things – a letter or money. If it is a letter, I do not know how to read. And if its money, I do not have anything to sell. So take your envelope and go." He will lose his life for this. These provinces will become the Cordillera Autonomous Region. In 1971, there are only tremors.

I turn 16 on April 16, an Ifugao festival for the end of rice planting. Out my window a double rainbow! All I want is Bontoc Hotel's signature breakfast of Nescafe coffee and tap-si-log which consists of tapas (dried meat), garlic rice, and itlog (a runny fried egg). Then another hike over the Chico and past the wake for an Igorot elder whose shrouded body, strung up on a rattan bed, decomposes in the cool high air. When we reach the town of weavers, I buy my own birthday shroud, a woven with blood-red and purple geometric designs.

So, you squat and await transport to Sagada where Ifugao hang coffins from cliffs. An Igorot woman shows me a green skein of yarn from her basket. I buy and keep it for another 16 years. We catch a third class Dangwa bus which is open-sided so you can peer over the cliffs as it careens around the turnabout. I'm not ready to go back to the bustling metropolis (Baguio or Manila). This is what I want to be doing at 36, I say to no one in particular.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed