There is no way to write about Yoling without a fearful nod to the devouring maw of Yolanda. The names of these November she-furies are now "retired." I never knew a wilder storm than Yoling in 1970, and I can't imagine the ferocious winds of this new era. For earlier reflection on Pagasa's names for storms and their impact, go back to my post Bagyo on Dading.

Both Yoling and Yolanda had a Kali-like ferocity. I am stricken with sadness at the suffering and hope of survivors, furious at those who capitalize on it, and obsessed with figures, stories and conditions of recovery.

Yoling was the mistress of her own historical moment. She was the twenty-seventh named storm and seventh super typhoon of the 1970 Pacific typhoon season. Yoling was the deadliest typhoon to sweep through Manila until Ondoy in 2009. She was, in a small way, our Yolanda. I am telling 1970's stories, so let this be my envelope to hold this larger disaster.

Yoling was the mistress of her own historical moment. She was the twenty-seventh named storm and seventh super typhoon of the 1970 Pacific typhoon season. Yoling was the deadliest typhoon to sweep through Manila until Ondoy in 2009. She was, in a small way, our Yolanda. I am telling 1970's stories, so let this be my envelope to hold this larger disaster.

Yoling was the whip-tail of the 1970 "triplet" storms, separated only by days or weeks. The most fierce was Typhoon Sening, third most deadly storm through Luzon til Yolanda, a super typhoon at 175 mph (275 kph). It left thousands homeless and 500 dead. Typhoon Titang followed a few days later. Its single fatal landfall left 600 dead. But we Manilenos remember Yoling with more dread. She cut straight across Luzon from November 17 though 20. Yoling ran amuck, with a peak intensity of 155 mph or 250 kph diminished to 130 mph when she arrived in Manila, but she was still a fury.

I was babysitting at the gracious Makati manse of Rev. Leon, pastor of Union Church, the American church in Manila. "Ok, I will be their American ate." I'd been pleased when Rev. Leon asked me to stay with the kids while he and his wife took a short trip to Hong Kong. I didn't know the kids, but Union Church library had fed my craving for Nancy Drew, Ozma, Sherlock Holmes, The Witch of Blackbird Pond, and a host of literary creatures. I had deep utang. The Leon children were 7, 5 and 1 ½. We were a houseful, since the yaya of the infant, a cook and driver were also there.

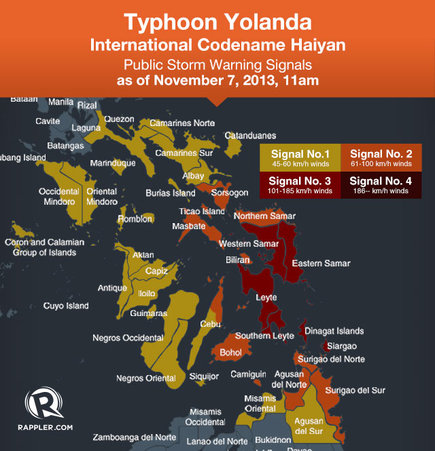

Memory is murky from this distance, and I don't remember any of their names. But I do know Typhoon Signal Number Three alarmed us (with the memory of Sening so fresh). We knew to prepare for the worst. Since there would soon be no phone-electricity-water, I called my Basilan Road family to check in and for reassurance. Three little children in Signal #3 is a bad convergence. The cook checked the fridge; we prepared candles for a dark night and the yaya wisely set up a play room in the back study. Makati had a patrician feel in the 1970's with expansive parks and sturdy two story homes. But Yoling respected no one. She arrived in a fury, stripping off prim red roofs and hurling them across the field. She was wild, wild, downing acacias and palm trees; she ripped out their foliage like hair. The Leon house was not spared. An hour into the storm, the sliding glass doors shattered and wet wind whipped through the lanai and living room. Glass spattered in a whirl of rain and sharp wind. We played in the back room. "Where are mommy and daddy?" they asked.

Then, that sound of iron ripping off its nails, a hair-raising metal screech as the roof rips off. Now we could hear the wind in wrap-around sound. I ran upstairs trying to decide what to save. Up in the muddy sky, the storm kept singing to itself. Here, it set its wet skirt down on the bedrooms - the mattress drunk and soppy, and bureau in wild disarray. What to save, so I scampered in teenage wisdom: electronic equipment first, and sticking them in closets, between sheets to hide from potential looters (the Lyons themselves called to ask where I'd hidden things it later on.) After several trips I joined everyone in the study room. It was a dismal sight. The little one buried her face in her yaya's breast, too frightened to cry, and the little boy looked up at me drenched with misery.

For a moment the howling ceased. I slipped out to the front yard and looked up. Her purple bruise of an eye gazed down, assessing her damage. I gave her silent tribute. The second winds seemed less terrible. As her final wave of hurling winds left us, the staff and I assessed the damage. The house was wilted, wet and dangerous, but the kitchen and their room was dry. Concerned about our safety the kind driver returned from his own home. Perhaps if I'd known someone in their church, we would have stayed in Makati, but, like the children, I wanted my family. "Bantayan ako ditto," the cook assured us, more brave than she felt, I'm sure. So the rest of us piled into the car for the tortuous post-Yoling trip along Hiway 54 -- past downed trees and telephone poles, tangled and dangling electric wires, over Guadalupe Bridge and shattered homes, past Fort Aguinaldo and Camp Crame, through flooded Cubao, around the rotunda past Quezon Boulevard to Philam homes. We stalled a few times in the flooding and gasped at the damage. People milled everywhere, shell shocked but already assessing damage for recovery.

PhilAm houses fared a little better because they were low. "Kerry!" mom exclaimed, surprised to find me at the door with two children, a yaya and baby in tow. The following day was bright, hot, and blue. But there was no electricity or water and the food in the fridge was spoiling. The Basilan road house of eight eased its shoulders to take in another four. The littlest cried without ceasing; absorbing the anxiety of her siblings. Brother and sister, certain they had been abandoned, played politely with us or quietly on their own, as hostages might who want their tormentors to forget them. "When are mommy and daddy coming?" "Soon," said mom in a way only mothers know. There was enough to do, waiting in lines for water at the fire hydrant, clearing brush, trying to find food for all of us, and how others were faring. Mom telegraphed the parents. "Oh, don't tell them," I begged her. Don't ruin their holiday. Now I think, what planet denial was I living on? Two days later, guilty anxious parents swept up their orphaned children. I don't remember seeing them again.

Yoling left misery behind her. Manila, bruised and battered, did not get up so easily. But we Americans woke up on Thanksgiving morning and the electricity had come on. All old plans revived, we had an impromptu pot luck with some SS Wright families, eating spaghetti, casserole, salad and then a song fest, truly thankful to be together, intact, and dry. We found each other and collected stories - who had or hadn’t escaped.

Mom says it was a tale of deliverance and survival. Manila had suffered a great blow. But it was blow upon blow - a longue durée of the first quarter storm. And it was a year of storms: strikes, demonstrations, earthquakes, winds and rains.

As a gift for this long suffering year, Pope Paul VI arrived in late November for the Pan Asian Bishops Conference. This was the first Papal Visit to the Philippines, the only Catholic nation in Asia. Dad told us that squatters hoped to present the pope with a manifesto and I will tell you more of this story in a little while. Imelda had built him the Coconut Palace but he wouldn't stay in it. Get behind me, you can hear him mutter, as though he knows what's coming.

But if Yoling and Yolanda are cousins, I wager another Pope might visit the Philippines soon.

I was babysitting at the gracious Makati manse of Rev. Leon, pastor of Union Church, the American church in Manila. "Ok, I will be their American ate." I'd been pleased when Rev. Leon asked me to stay with the kids while he and his wife took a short trip to Hong Kong. I didn't know the kids, but Union Church library had fed my craving for Nancy Drew, Ozma, Sherlock Holmes, The Witch of Blackbird Pond, and a host of literary creatures. I had deep utang. The Leon children were 7, 5 and 1 ½. We were a houseful, since the yaya of the infant, a cook and driver were also there.

Memory is murky from this distance, and I don't remember any of their names. But I do know Typhoon Signal Number Three alarmed us (with the memory of Sening so fresh). We knew to prepare for the worst. Since there would soon be no phone-electricity-water, I called my Basilan Road family to check in and for reassurance. Three little children in Signal #3 is a bad convergence. The cook checked the fridge; we prepared candles for a dark night and the yaya wisely set up a play room in the back study. Makati had a patrician feel in the 1970's with expansive parks and sturdy two story homes. But Yoling respected no one. She arrived in a fury, stripping off prim red roofs and hurling them across the field. She was wild, wild, downing acacias and palm trees; she ripped out their foliage like hair. The Leon house was not spared. An hour into the storm, the sliding glass doors shattered and wet wind whipped through the lanai and living room. Glass spattered in a whirl of rain and sharp wind. We played in the back room. "Where are mommy and daddy?" they asked.

Then, that sound of iron ripping off its nails, a hair-raising metal screech as the roof rips off. Now we could hear the wind in wrap-around sound. I ran upstairs trying to decide what to save. Up in the muddy sky, the storm kept singing to itself. Here, it set its wet skirt down on the bedrooms - the mattress drunk and soppy, and bureau in wild disarray. What to save, so I scampered in teenage wisdom: electronic equipment first, and sticking them in closets, between sheets to hide from potential looters (the Lyons themselves called to ask where I'd hidden things it later on.) After several trips I joined everyone in the study room. It was a dismal sight. The little one buried her face in her yaya's breast, too frightened to cry, and the little boy looked up at me drenched with misery.

For a moment the howling ceased. I slipped out to the front yard and looked up. Her purple bruise of an eye gazed down, assessing her damage. I gave her silent tribute. The second winds seemed less terrible. As her final wave of hurling winds left us, the staff and I assessed the damage. The house was wilted, wet and dangerous, but the kitchen and their room was dry. Concerned about our safety the kind driver returned from his own home. Perhaps if I'd known someone in their church, we would have stayed in Makati, but, like the children, I wanted my family. "Bantayan ako ditto," the cook assured us, more brave than she felt, I'm sure. So the rest of us piled into the car for the tortuous post-Yoling trip along Hiway 54 -- past downed trees and telephone poles, tangled and dangling electric wires, over Guadalupe Bridge and shattered homes, past Fort Aguinaldo and Camp Crame, through flooded Cubao, around the rotunda past Quezon Boulevard to Philam homes. We stalled a few times in the flooding and gasped at the damage. People milled everywhere, shell shocked but already assessing damage for recovery.

PhilAm houses fared a little better because they were low. "Kerry!" mom exclaimed, surprised to find me at the door with two children, a yaya and baby in tow. The following day was bright, hot, and blue. But there was no electricity or water and the food in the fridge was spoiling. The Basilan road house of eight eased its shoulders to take in another four. The littlest cried without ceasing; absorbing the anxiety of her siblings. Brother and sister, certain they had been abandoned, played politely with us or quietly on their own, as hostages might who want their tormentors to forget them. "When are mommy and daddy coming?" "Soon," said mom in a way only mothers know. There was enough to do, waiting in lines for water at the fire hydrant, clearing brush, trying to find food for all of us, and how others were faring. Mom telegraphed the parents. "Oh, don't tell them," I begged her. Don't ruin their holiday. Now I think, what planet denial was I living on? Two days later, guilty anxious parents swept up their orphaned children. I don't remember seeing them again.

Yoling left misery behind her. Manila, bruised and battered, did not get up so easily. But we Americans woke up on Thanksgiving morning and the electricity had come on. All old plans revived, we had an impromptu pot luck with some SS Wright families, eating spaghetti, casserole, salad and then a song fest, truly thankful to be together, intact, and dry. We found each other and collected stories - who had or hadn’t escaped.

Mom says it was a tale of deliverance and survival. Manila had suffered a great blow. But it was blow upon blow - a longue durée of the first quarter storm. And it was a year of storms: strikes, demonstrations, earthquakes, winds and rains.

As a gift for this long suffering year, Pope Paul VI arrived in late November for the Pan Asian Bishops Conference. This was the first Papal Visit to the Philippines, the only Catholic nation in Asia. Dad told us that squatters hoped to present the pope with a manifesto and I will tell you more of this story in a little while. Imelda had built him the Coconut Palace but he wouldn't stay in it. Get behind me, you can hear him mutter, as though he knows what's coming.

But if Yoling and Yolanda are cousins, I wager another Pope might visit the Philippines soon.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed