leaves for a world tour by mid-1964

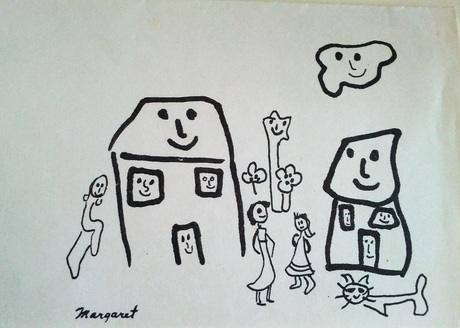

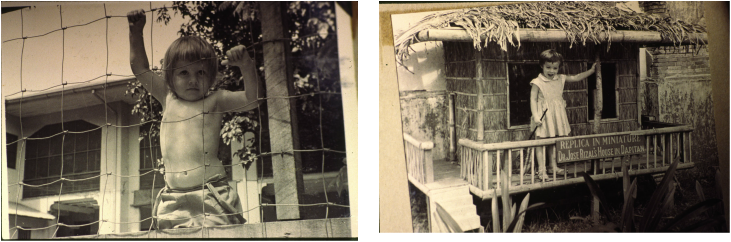

It's Christmas again (from Manila)

And we’ve tried very hard

To get a family photo

For our Christmas card

We’ve tried it for years

But it never works.

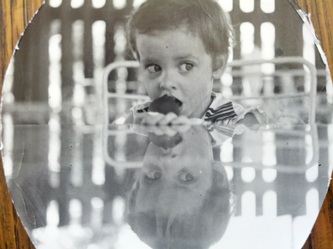

Somebody cries,

And somebody smirks

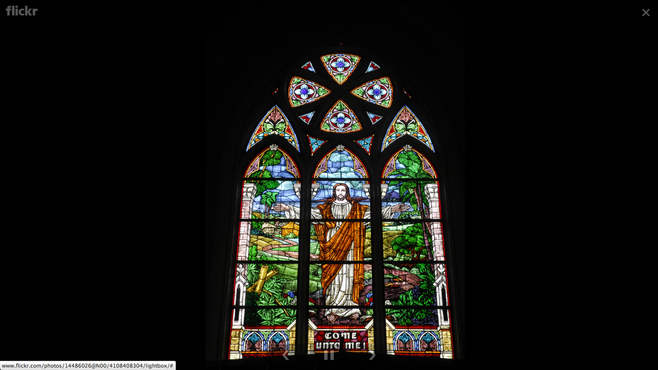

The problem is not

Uniquely ours,

We see it as a world-wide

Clash of powers.

To get a smile

On the whole world’s face

Is a hope as old

As the human race.

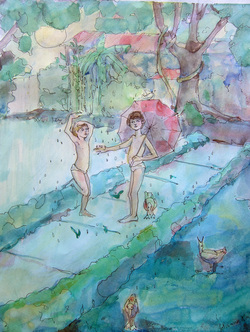

So the picture in words

We present to you

Of the joys of life

We all go through

Merry Christmas

And a Good year too

RSS Feed

RSS Feed