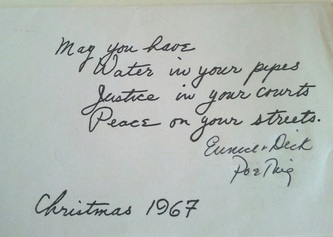

My father interprets the context for the “Battle of Mendiola” in an Easter letter to his network and extended family.

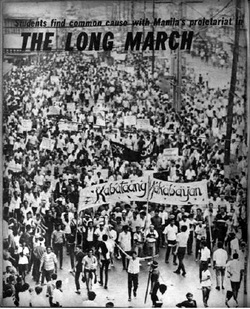

In front of Malacanang is a section of old two-story frame Spanish-style houses. The wide street, Mendiola, in front of Malacanang, leads to the university district of Manila. A few blocks from the palace over 200,000 students live and study in about a half-dozen universities…a crowded, sordid district of decaying boarded houses, and high-rise classroom buildings divided from each other by narrow sidewalks…Cement, smoke-belching buses, overloaded jeepneys, neon-lighted clothing stores, cubby-hole second-hand bookstores, and endless young people who attend school in shifts—these are the features of Sampaloc. Sampaloc—the student district—faces Malacanang with all the questions about why things are the way they are in the Philippines today.

The students fight police at Mendiola all night long. Lacaba recounts in Days of Quiet, Nights of Rage,

About seven times the cops attacked; about seven times they retreated, often on the run, an army routed by a band of children. Each time they attacked, the cops grew more frenzied, maddened and bewildered by a defiance they had not expected and could not understand.

Demonstrators also surge on the American Embassy on Roxas Boulevard across from Luneta Park, shouting “Yankee go home!” They rip off the US seal from the wall and toss Molotov cocktails over the fence. When the US Marines arrive, the crowd retreats, burning cars and smashing windows. One newspaper notes ironically that students destroy a restaurant called The Front, with posters of Marx and Mao, but don’t touch The American restaurant.

In the next three months, jeepney drivers stage a series of wildcat strikes when Marcos devalues the peso and the gasoline prices rise. Cycles of rallies-to-riots spice up our commute to Padre Faura since Quiapo is a hub of action. At UP Prep, Scott's radical classmates accuse our father of CIA affiliation. It's the “First Quarter Storm.” Mirroring student uprisings globally, we are caught up in a protracted rage of things as they are: American militarism in the Pacific and its stranglehold on Philippine politics, peaking oil prices, Marcos's staged comeback and the increasing militarism of everything.

Johanna's Marxist history teacher at JASMS invites the class to a "mass action."

"No," says mom firmly and shakes her head, "No, you can't."

"But dad is working with those Maryknoll guys and they have demonstrations against housing demolitions!"

"No. You're American girls. It's too dangerous."

So, with school cancelled again, we take to the privacy of the roof, listening for updates. A few friends are at the rally. We are silly in a stupid way.

“What’s dis pers quarter storm, tawad sa isang piso storm?”

“Bakit kaya wala kaming notification? Not even “we regret to inform you that due to di fak dat you are a running dog imperialista and your fadder is a CIA, you are not invited to di mass aksyion.”

“CIA kaya ang fadder namin?”

Tanga! Ip so, why no PX? Bakit walang Seventeen Magazine? Belib in me mare, our fadder is BIA – Balding in Action, pero no CIA.”

"Stupida!"”

I turn up the radio for more news.

Manila is roiling. We roil with it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed